Shopping for Bank Regulators

Banks in the United States have long had choices between state and federal banking authorities

This past September, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) approved Fifth Third Bank's application to convert from a state charter to a national charter. The main purpose of the switch, according to the bank, was to streamline its regulatory process. As one of the largest U.S. banks, Fifth Third operates across many states and believes that "a national charter will be more efficient, given national banks are regulated and examined by the OCC, rather than on a state-by-state basis," bank spokesman Gary Rhodes said in an email statement.

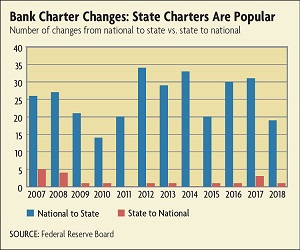

But Fifth Third's switch was a bit of an anomaly, because most charter changes since the financial crisis have been in the other direction, with small community banks switching from national charters to state charters. These small banks have been attracted by "the closer proximity and more customized treatment offered by state regulators," says Arthur Wilmarth Jr., a George Washington University law professor who specializes in bank regulation. "If you are a small bank, you are more likely to get your phone call answered and sit down with a state regulator compared with the OCC."

Banks' freedom to choose between state and federal charters has long been a feature of the U.S. banking system. This dual regulatory approach, which puts state and federal regulators in competition with one another, stands apart from the consolidated systems of many other advanced economies, including Canada, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. For this reason, among others, the merits and shortfalls of the U.S. dual regulatory system have been vigorously debated. And while many analysts have focused on the benefits of "healthy regulatory competition," others have also pointed to historical episodes in which regulatory competition has devolved into a "race to the bottom," with costly results.

The Major Players

In the years immediately preceding the Civil War, bank regulatory authority in the United States had resided at the state level. That changed when the OCC was established in 1863, primarily as a response to the imperatives of Civil War deficit financing. The new institution offered national bank charters under the condition that banks maintain certain capital adequacy standards and minimum government bond holdings. In return, nationally chartered banks would be able to issue national bank notes, which would trade at close to par value, based on their full backing by holdings of Treasury securities. At the time, bank notes were essentially bank IOUs redeemable in gold, and the notes of state-chartered banks often traded at discounts to par value, reflecting both the uncertainty and transportation costs associated with their redemption.

"The Consolidation of Financial Regulation: Pros, Cons, and Implications for the United States," Economic Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 2, Spring 2009

"Competition Among Bank Regulators," Economic Quarterly, vol. 88, no. 4, Fall 2002

But the establishment of the OCC did not initially achieve the government's fiscal goals. Many banks balked at the supervisory standards associated with national charters, which were perceived to be more stringent than those typically associated with state charters. In response, Congress imposed a 10 percent tax on the issuance of state bank notes in 1865. The tax proved to be severe enough to lead most state banks to take out national charters, allowing them to issue untaxed national bank notes.

The tax on state bank notes had tipped the scales in favor of national bank charters, but that advantage did not last long. In the decades following the Civil War, the use of checking accounts became increasingly widespread due to their convenience and untaxed status. This development reduced the relative attractiveness of national bank charters — a trend that was reinforced by declining yields on the bonds that national banks were required to hold to back their notes. As a result, state bank charters enjoyed a resurgence. As this process unfolded, the breadth and quality of state bank supervision improved substantially.

The Federal Reserve System was established in 1913 in reaction to a long series of post-Civil War banking crises that culminated with the Panic of 1907. The U.S. banking system had suffered from periodic bouts of illiquidity associated with seasonal agricultural cycles, international gold flows, and domestic business cycle fluctuations. New York City clearing banks had provided some degree of liquidity support to correspondent banks, but the system had proved insufficient to adequately facilitate financial flows between regions and to avert panics, particularly in 1907. The Fed was created to improve the banking system's cross-regional plumbing and — crucially — to serve as a lender of last resort.

The Fed's regulatory role was a natural offshoot of its role as lender of last resort. In order for the Fed to engage in discount window lending, it would need to understand the creditworthiness of its counterparties. As originally written, the Federal Reserve Act gave both the OCC and the Fed authority to regulate national banks, but this regulatory overlap was soon removed. The OCC was tasked with supervising nationally chartered banks (and providing examination reports to the Fed), while the Fed was tasked with supervising state-chartered member banks. The Fed's supervisory mandate was extended to bank holding companies by the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956.

The third major federal bank regulator — the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) — was created by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 in reaction to the banking crises of the Great Depression. According to the FDIC, "Apparently the political compromise that led to the creation of the FDIC did not permit taking any supervisory authority away from existing federal or state agencies, so in 1933 the FDIC became the third federal bank regulatory agency, responsible for some 6,800 insured state [non-Fed-member] banks." Although the FDIC's supervisory role was thus circumscribed, it was assigned a broad mandate as the liquidator of failed banks by the Banking Act of 1935.

The Dual Banking System and the Financial Crisis

These historical developments have resulted in what is often referred to as the U.S. "dual banking system," which allows most banks to apply for charters either nationally or in the states where they operate. Banks with national charters are supervised and examined exclusively by the OCC, while state-chartered banks generally are examined on an alternating basis by their state regulators or one of the two primary federal regulators. The Fed serves this role for Fed-member banks, while the FDIC does so for non-Fed-member banks with state charters. Bank holding companies are an exception to this rule and are supervised exclusively by the Fed.

An advantage of the dual banking system, according to many observers, is that it allows for healthy competition among bank regulators. Because financially sound banks are allowed to change charters, regulators have an incentive to control fees, innovate, and remove unnecessary red tape from the supervisory process. Another arguable advantage of the dual regulatory system is that it fosters the development of smaller banks — viewed by many as responsive to local community needs — because it gives them the opportunity to seek improved access and customized services through a regulator that is closer to home.

But the dual banking system is not without potential problems. In principle, banks are supposed to face the same regulatory standards, regardless of whether they choose state or federal charters. Some analysts, however, have argued that the system's allowance for banks to shop for regulators has sometimes encouraged regulators to compete for banks by offering overly accommodative supervisory services. Proponents of this view have pointed to a number of pre-financial-crisis examples to make their case.

For some observers, Colonial Bank (Colonial) of Montgomery, Ala., stands out as a cautionary tale of the pitfalls of regulator shopping. From 1997 to 2008, the bank switched regulators three times — effectively doing a full loop of all the regulatory possibilities. As a state-chartered bank in 1997, it became a Fed member and thus opted for the Fed as its primary federal regulator in place of the FDIC. Then, in 2003, the bank switched to a national charter and thus came under OCC supervision. Finally, in 2008, Colonial switched back to an Alabama state charter, discontinued its Fed membership, and thus opted to have the FDIC as its primary federal regulator.

Colonial's final shift was the most problematic. Prior to 2007, the OCC had consistently rated the bank as a well-performing institution. But the OCC's August 2007 examination found serious risks in Colonial's loan portfolio and management practices — so much so that the OCC was in the process of downgrading Colonial's risk rating and drafting a cease and desist order. But due to Colonial's pursuit — and June 2008 attainment — of a charter change, the bank's problems had not been documented in a formal examination report and the cease and desist order had not been imposed. The OCC coordinated efforts with the FDIC and the Alabama State Banking Department during the regulatory hand-off. Not long thereafter, the enormity of Colonial's problems came to light, and the FDIC and Alabama State Banking Department shut the bank down in August 2009. The bank's failure turned out to be one of the biggest of the financial crisis.

The now-defunct Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) is viewed as providing a noteworthy example of regulatory laxity and over-accommodation in the run-up to the financial crisis. The OTS was formed in 1989 in response to the U.S. savings and loan crisis with the mandate of chartering and supervising thrifts, savings banks, and savings and loan associations. At first, the OTS was perceived to be a strong regulator, but subsequently its standards appear to have deteriorated. Faced with declining fee income from the institutions it regulated — the OTS's primary source of revenue — the regulator attracted new "customers" by offering lax supervisory oversight, according to some accounts.

One such customer was Countrywide Financial, which switched from being a national bank under OCC supervision to being a thrift under OTS supervision in 2007. The OTS allowed Countrywide to modify terms on problem loans and thereby delay loan foreclosures. This, in turn, allowed Countrywide to present outside observers with an overly rosy picture of its financial health. In the end, some of the biggest failures of the financial crisis had been under OTS supervision, including Countrywide, American International Group, IndyMac, and Washington Mutual.

There is some evidence that, prior to the financial crisis, banks may have been able to achieve better regulatory ratings by switching charters. Better ratings are desirable for banks, because poor ratings can increase regulatory fee assessments, increase examination frequencies, and delay the approval of bank expansion plans. In a 2014 study, Marcelo Rezende of the Federal Reserve Board looked at groups of banks with the same initial ratings and compared the subsequent ratings of those that had changed charters to those that had not. He found that banks that had switched charters tended to receive better ratings than those that had not. "The results are consistent with the view that regulators compete for banks by rating incoming banks better than similar banks that regulators already supervise," wrote Rezende. He also found that after controlling for initial bank ratings, banks that had switched charters subsequently failed more often.

Aftermath of the Financial Crisis

Federal regulators reacted to some of the system's perceived problems as early as July 2009 in a Statement on Regulatory Conversions issued by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) — a formal interagency body established to promote uniform standards across federal regulatory institutions, including the OCC, the Fed, and the FDIC, among others. The FFIEC statement was meant to convey that federal supervisors were unified and would not "entertain" conversion requests submitted while serious enforcement actions are pending, "because such requests could delay or undermine supervisory actions." Similar restrictions on regulatory conversions were subsequently codified under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, popularly known as the Dodd-Frank Act.

The Dodd-Frank Act changed the relationship between federal and state banking laws. By creating the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, it expanded federal law to an area that had historically been dominated by state law. In principle, rules set by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau would create a regulatory ground floor spanning all state jurisdictions.

The new legislation also contained provisions that substantially reduced the application of a doctrine known as "federal preemption" to the dual banking system. Historically, the concept of federal preemption has been an important inducement for banks to choose national charters rather than state charters. The Supreme Court has held that nationally chartered banks are exempt from state banking laws that "significantly interfere" with powers granted under the National Banking Act of 1864. This interpretation has allowed the OCC to issue broad rules that preempt state banking laws. This has been attractive for many large banks, because it allows them to avoid many legal constraints and liabilities across multiple state jurisdictions. In two prominent examples, JPMorgan Chase and HSBC switched from New York state charters to national charters in the aftermath of a 2004 OCC ruling that expanded the scope of federal preemption (into, among other areas, antipredatory lending law).

The Dodd-Frank Act substantially limited the scope of federal preemption by "restricting some of the things the OCC can do by regulation," says John McGinnis, a professor of law at Northwestern University. "So if the OCC decides to preempt a state consumer protection law, they have to show that the state law has an actual discriminatory effect against national banks or significantly interferes with their powers under federal law." This restriction increased the power of states to enforce their own consumer protection laws against nationally chartered banks, and it thereby placed limits on the ability of banks to avoid state regulations by switching to national charters.

Other policy changes have also limited banks' incentives to switch charters. Since the early 1980s, there has been a convergence of many of the obligations and prerogatives of state and nationally chartered banks. Under current federal rules, for instance, all depository institutions are required to maintain Fed-mandated reserve levels and are allowed to use the Fed's discount window and check-clearing services. Moreover, many states have enacted "wild card" or "parity" statutes that grant state-chartered banks the same banking powers as national banks operating in the same state.

Moves to level the regulatory playing field have tended to enhance the relative attractiveness of state charters, and state regulators have made the most of the situation by actively marketing their services. Tennessee, for example, promotes its greater accessibility, lower fees, and close working relationships with primary federal regulators (the Fed and FDIC) and other state regulators through the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. And Texas emphasizes "lower costs," "super parity," and "new initiatives" to improve efficiency.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.