Community Colleges in the Fifth District: Who Attends, Who Pays?

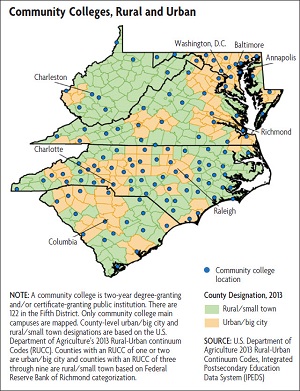

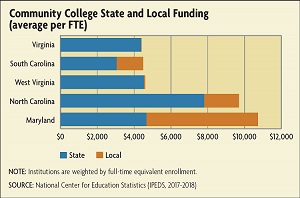

While community colleges existed in the United States as early as 1901, the boom began in the 1940s with the introduction of the GI Bill and the return of veterans from World War II. Today, these institutions are a major force in higher education: In fall 2017, more than 605,000 Fifth District residents were enrolled in a community college, with 64.9 percent of them attending on a part-time basis. Several states, including Maryland and West Virginia, have passed legislation within the past two years that will make community college tuition free for most state residents.

Given the need for more skilled workers and the increased financial support for community college students, one might expect enrollment to be growing. Instead, after growing for many years, community college enrollment in the Fifth District has been declining recently, including a 1.8 percent decrease between fall 2016 and fall 2017. Some of this decline undoubtedly stems from the strong economic conditions and low unemployment rates. Indeed, the size and composition of community college enrollment has long varied with the economic cycle: During times of higher unemployment, community colleges have seen surges in enrollment, especially in fields related to skilled trades; during times of economic growth, enrollment in technical programs has decreased and schools have relied more on their programs oriented toward college transfer.

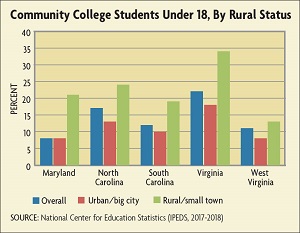

But there are other factors at play, including the fact that the number of high school graduates in the United States has been stagnant since around 2011. This trend and others are shaping the role of community colleges in education and workforce development.

"Transitioning from High School to College: Differences across Virginia," Economic Brief No. 17-12, December 2017

"The Role of Option Value in College Decisions," Economic Brief No. 16-04, April 2016

Each of the five states in the Fifth District have additional scholarship and grant programs that can be used by community college students. Examples include the Virginia Commonwealth Award Program, which provides students with demonstrated need a grant that can cover up to the cost of tuition if they are enrolled in at least six credit hours per semester. Another example is the lottery-funded South Carolina Lottery Tuition Assistance Program. This grant provides South Carolina residents who don't qualify for the state's LIFE Scholarship, which has more stringent qualification standards, $1,140 a semester to attend community college as long as they are registered for at least six credit hours.

While the amount of state and federal aid available to community college students appears to be plentiful, there is one important caveat. Nearly all of the programs previously discussed, including Pell Grants and federal loans, can be used only by students in for-credit programs. This means students who wish to attend community college to obtain a noncredit certificate are ineligible for most grants and scholarships. This is true for both federal grants and aid as well as for most of the primary state-level scholarship or grant programs in the Fifth District. While some states are trying to work toward addressing the issue — the South Carolina legislature appropriated $11 million in 2018 for workforce scholarships — the overall limitations that low-income students face in attending these programs persist.

Commercial driver's license (CDL) programs are an example of the potential value of noncredit programs. Like most noncredit programs, CDL programs tend to be very short term; a typical CDL program lasts only around seven weeks. Yet the certification can lead to solidly middle-class wages. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, median pay for truck drivers with a CDL in the United States was $21 per hour, or $43,680 per year, in 2018. There is also a reported shortage of 60,000 drivers, according to the American Trucking Association. The math seems simple. The pay is relatively high, there is a shortage in the market, and programs exist at many community colleges. Yet given the funding challenges, it's not as straightforward as it may seem. One Fifth District community college reported that their CDL program hasn't been offered in two years because of lack of enrollment. They report that it is entirely because of the nearly $2,000 price tag and the lack of financial aid for these programs.

Measuring Success

A common measure of an institution's success is its graduation rate. For community colleges, however, this measure can be an uneasy fit.

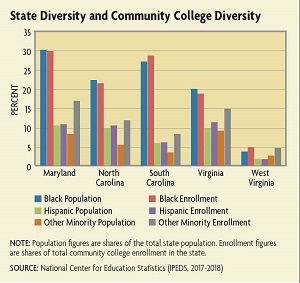

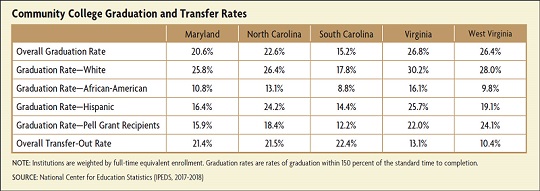

The federal government defines the graduation rate as the percentage of a school's "first time, first-year undergraduate students who complete their program within 150 percent of published time for the program." So for associate degree students, the graduation rate measures the percentage of students who finish the degree within three years, as nearly all associate degree programs have a published completion time of two years. In the case of community colleges, graduation rates have historically been quite low. In 2017-2018, the graduation rates at community colleges averaged lower than 27 percent in each of the five Fifth District states, with the lowest being 15.2 percent in South Carolina. The results are even more concerning when broken down by race and income. Black students have far lower graduation rates than white students in all five states, ranging from 8.8 percent in South Carolina to 16.1 percent in Virginia. Pell Grant recipients also fare worse, with lower graduation rates than average in each of the Fifth District states. (See table.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.