The Repo Market is Changing (and What Is a Repo, Anyway?)

The market for repurchase agreements has repeatedly adapted to changing circumstances

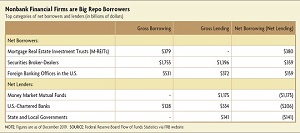

Repo markets played a prominent role in the 2004-2007 real estate boom and the ensuing financial crisis. In just four years, between December 2003 and December 2007, the asset-to-equity ratio of U.S. broker-dealers ballooned from 24:1 to 35:1. And this balance sheet expansion relied heavily on repo borrowing.

Lehman Brothers, in particular, relied heavily on the tri-party repo market to finance its securities inventory, which ended up being dangerously concentrated with illiquid mortgage-backed securities. By mid-2007, market participants had become concerned about Lehman's leverage as well as the quality of its asset holdings, and the firm's management embarked on a campaign to reduce the firm's leverage. But Lehman found itself with a dilemma. It was loath to raise equity capital, because firm management thought that would send a bad signal to the markets. But it found that reducing leverage through asset sales was just as problematic, because it could not sell assets without booking losses — and the recognition of those losses would seriously undermine the collateral value of the firm's remaining assets, which it relied on for repo market financing.

Although Lehman continued to present itself as solvent in its quarterly financial reports, market observers became increasingly skeptical. In addition to questionable asset valuation methods, it was later discovered that the firm had misrepresented its leverage by improperly pushing certain repo liabilities off its balance sheet at the end 2007 and in early 2008. After Bear Stearns was shuttered in March 2008, market participants became even more concerned about a run on Lehman Brothers. The firm finally declared bankruptcy in September 2008 — an event that seriously strained financial markets.

The runs on Bear Stearns and Lehman highlighted the risk that highly leveraged firms face from collateral "fire sales" — the risk that the forced liquidation of asset holdings can dramatically depress the market prices for collateral and thereby set off a vicious cycle that culminates in a run. This risk is greatest when a firm's assets are risky, opaque, and therefore illiquid — a description that fit much of the two firms' holdings of mortgage-backed securities.

The tendency toward a vicious cycle appears to have been amplified in the tri-party repo market by lenders' behavior in the face of declining and uncertain collateral valuations. Several studies have examined the discounts — known as "haircuts" — that tri-party repo lenders applied to reported collateral valuations as the crisis unfolded. A well-known 2010 study by Adam Copeland, Antoine Martin, and Michael Walker of the New York Fed found that lenders in the tri-party repo market generally did not increase collateral haircuts in response to increased counterparty risk during the financial crisis. Rather, lenders were more inclined to require higher-quality collateral or deny lending altogether. This behavior likely contributed to the precipitousness of the Bear Stearns and Lehman collapses.

A great deal of risk was rooted in the tri-party market's structure. The U.S. tri-party repo market was dominated by two clearing banks, BNY Mellon and JPMorgan Chase. According to regular practice, all tri-party repo contracts (even multiday contracts) would be unwound on a daily basis — meaning that collateral would be shifted back to a borrower's securities account at its clearing bank and cash would be shifted back into the lender's cash account at the same clearing bank. This had the advantage of giving borrowers maximum flexibility to use their collateral intraday, but it had the disadvantage of regularly leaving clearing banks with huge intraday exposures to repo borrowers. It was not uncommon for a single broker-dealer to owe its main clearing bank more than $100 billion intraday.

This feature of the tri-party repo added an additional layer of complexity to a risky game. In the midst of the crisis, repo lenders not only had to be wary of other repo creditors quickly exiting the market and leaving them "holding the bag," they also had to be wary of clearing banks deciding not to execute the daily unwind, which could leave repo lenders similarly exposed.

"Repo lenders are not interested in taking possession of collateral, and if they think they are going to be left holding it, they will say 'No, I won't lend to you,'" says Richmond Fed economist Huberto Ennis, who has studied strategic behavior in the tri-party repo market. "And if they think that the clearing bank is not going to unwind the next morning, they are going to be happy holding onto their cash and losing one night's interest."

Post-Crisis Reforms

The Task Force on Tri-Party Repo Infrastructure, which was formed to explore the market's problems, urged a number of changes to lower risk. In accord with task force recommendations, the clearing banks discontinued the daily unwind for nonmaturing loans. In addition, they substantially reduced their extension of intraday credit.

The crisis also led to major changes in monetary policy that fundamentally affected the functioning of repo markets. "The Fed's old system had been to target the federal funds rate by doing small, but regular, repo lending operations to adjust the supply of bank reserves," says William English of Yale University. "But this wasn't going to work anymore under quantitative easing. What ended up working, at least at first, was paying banks a set rate of interest on their reserves."

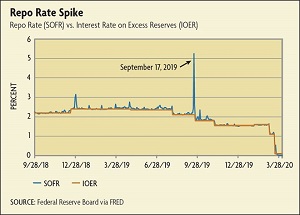

Before the financial crisis, the Fed had seldom borrowed funds in the repo market by engaging in what are called "reverse repos." But this changed in 2014 after the Fed's acceleration of quantitative easing caused short-term interest rates to decline below the rate the Fed paid banks on their reserves. At that point, the Fed created the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement Facility to stand ready to borrow funds from certain firms, including mutual funds, at a set rate. This helped the Fed reestablish a floor for market rates. Under this new system of interest rate targeting, which combined paying interest on bank reserves with the reverse repo facility, the Fed largely refrained from repo market lending — that is, until September 2019.

The financial crisis also gave rise to changes in bank regulation and supervision. Perhaps the most consequential changes for repo markets pertained to supervisory guidance and the use of stress tests.

Rate Spikes of Sept. 17, 2019

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.