Education without Loans

Some schools are offering to buy a share of students' future income in exchange for funding their education

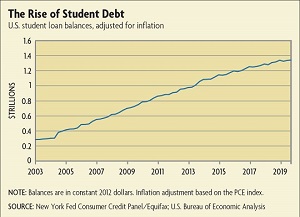

The cost of college has been rising. After adjusting for inflation, the average tuition for a private four-year school in 2019-2020 is about twice what it was three decades ago. For public four-year schools, tuition nearly tripled over the same period.

"Who Values Access to College?" Economic Brief No. 20-03, March 2020

"Slowing Growth in Educational Attainment," Economic Brief No. 18-07, July 2018

"The Role of Option Value in College Decisions," Economic Brief No. 16-04, April 2016

While ISAs might seem like a relatively new innovation, the idea has actually been around for decades. Famed economist Milton Friedman first wrote about them in 1955. He argued that loans are not the ideal way to fund investments in human capital because they require students to shoulder too much of the risk. Failure to launch leaves recipients of student loans making payments on an investment that didn't pan out. Moreover, it is difficult for students to offer lenders collateral for education loans, meaning such loans will be scarce and expensive absent subsidies.

Friedman argued that in the market, companies typically do not rely on debt to fund risky investments. Instead, they issue equity, asking investors to share some of the downside risk in exchange for a share of the profits if the investment works out.

"The counterpart for education would be to 'buy' a share in an individual's earning prospects: to advance him the funds needed to finance his training on condition that he agree to pay the lender a specified fraction of his future earnings," Friedman wrote.

While Friedman saw no legal hurdles to creating these types of contracts, he acknowledged that there were a number of reasons why they hadn't been widely adopted. Chief among them is the fact that ISAs are costlier to administer than debt. An ISA requires issuers to track borrowers' incomes, potentially over long time horizons and across different employers and geographic locations. Borrowers, in turn, have an incentive to hide their income to reduce payments, making administration that much trickier.

This may be why early attempts to implement Friedman's idea involved trying to graft some of the benefits of ISAs onto debt. In the 1970s, Yale University created the Tuition Postponement Option (TPO) with the help of Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin. The plan grouped student borrowers into cohorts who agreed to pay Yale a percentage of their future income until the entire cohort's debt plus interest was repaid. Borrowers could buy their way out of the program early by paying 150 percent of their total award plus interest.

While the program somewhat resembled Friedman's idea by tying payments to income, the fact that each individual was responsible for the collective debt of the group proved disastrous. Wealthier borrowers and those who had borrowed small amounts bought their way out of the program early. Those who remained in each cohort either failed to make payments or were left paying shares of their income for decades on a negatively amortizing principal. Yale stopped accepting new applicants for the program in the late 1970s and ultimately canceled remaining debts in the early 2000s.

"I think what people learned from the Yale program was that making someone's payments contingent on what others pay is a bad idea," says Miguel Palacios, a professor of finance at the University of Calgary. He has written extensively about ISAs and co-founded Lumni, a venture that finances ISAs across the Americas.

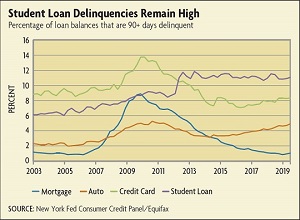

Successors to Yale's program made payments tied to the individual but still tended to be based on debt. President Bill Clinton, a participant in Yale's TPO, proposed the first income-based repayment plan in the United States for federal student loans. Today, recipients of federal student loans can qualify to make their monthly payments proportionate to income. On the surface, this allows federal loans to offer many of the same benefits of ISAs to students. But like the Yale experiment, these plans are still susceptible to ballooning interest payments.

"If you experience hardship and have to make smaller payments on a loan, it can negatively amortize — it can get bigger," says DeSorrento. Moreover, while income-driven repayment plans for federal loans allow borrowers who make regular payments to have their remaining balance forgiven after 20 or 25 years, the amount forgiven can be taxable as income. This would leave some borrowers who are unable to pay their loans with a hefty tax bill.

"ISAs don't work that way," says Pianko. "They're not debt, so at the end of the payment period, any remaining obligation just expires."

Balancing Costs and Benefits

Given the many benefits ISAs offer students over debt and the fact that schools can use them to signal the quality of their programs, why has the idea been so slow to catch on since Friedman's proposal? As he recognized at the time, it has to do with balancing costs to ensure that schools and other investors have enough incentive to offer ISAs.

"A fundamental difference between what Friedman wrote and how ISAs have actually been implemented is that Friedman was thinking about something that had no upper cap on repayments," says Palacios. "So if Bill Gates had taken out an ISA while in school, the issuer would have made billions of dollars."

That kind of upside would be one way to incentivize schools or private investors to offer ISAs, but most ISAs today do have a cap on total payments. While caps offer students additional protection, they limit how much investors can recoup from successful students to offset losses from students who end up paying back less. For some institutions, this might not be too big a concern.

"We work with schools that intentionally offer ISAs to students who are high risk and might not succeed because they want to try to help them," says DeSorrento. "The vast majority of Vemo's ISA programs are subsidized by the schools."

These subsidies might be partially offset by the increased prestige and enrollment ISAs generate for a school, something that Vemo estimates for its school partners. Schools might also regard some degree of losses on ISAs as consistent with their missions, treating the ISAs as analogous to financial aid that recipients may or may not pay back. Purdue's ISA, for example, is funded by money from donors. Any ISA payments they receive go to fund additional ISAs or other affordability programs. Private training academies, as for-profit institutions, are less likely to be able to rely on donors to fund their ISAs.

The decision of how to fund contracts in the short term could affect how well the ISAs align the interests of school and students. For example, online coding academy Lambda School works with Edly, an online marketplace for the sale of ISA contracts to investors. This provides Lambda with some operating capital upfront while it awaits student payments. While Lambda has indicated that it still finances some of its operations itself, retaining "skin in the game," some critics have argued that selling ISAs to private investors weakens the alignment of incentives between Lambda and its students.

"The institution still has an incentive to serve its students well because if the investors who put money in the program don't see returns, then those investors will not continue financing the ISAs," says Palacios. Indeed, Lambda says that the advances it receives from investors adjust based on how well its graduates do in the job market. "But that link is weaker than if the institution's money was directly on the line," Palacios adds.

"Schools should have significant skin in the game," agrees Pianko. "It makes sense for schools to work with investors to get some capital up front to provide services to students. But the key is structuring the ISAs so that the school retains the first-loss piece. In the case of University Ventures, we require any schools we finance to keep a large portion of the risk. If the students don't have the economic success they hoped for, then the school doesn't get paid as much."

It remains to be seen whether the institutions now offering ISAs can balance the costs in a way that sustains their program over the long term while maintaining the benefits of risk-sharing and downside protection for students. Although ISAs are now offered at a growing number of colleges and vocational training programs, these programs are only a few years old at this point.

The Future of Education Finance?

While proponents of ISAs would like to see them become more widespread in educational finance, there are a few factors that may keep them a niche option, at least for now.

Student loans have a well-established regulatory and legal framework, but lawmakers are still deciding how best to allow innovation in ISAs while protecting students from predatory agreements. In July 2019, Sen. Todd Young (R-Ind.) introduced a bipartisan bill to legally define ISAs and establish requirements for a "qualified ISA," including caps on the share of income lenders can charge and the duration of contracts. The bill has yet to progress any further. As long as the regulatory environment remains murky, investors and schools may be hesitant about ISAs.

On the other hand, Vemo has seen significant growth since it entered the market in 2016 with Purdue. Today, the company reports that it works with more than 75 schools and training programs to offer ISAs. DeSorrento believes that if those schools succeed with ISAs and start to attract students because of those programs, it will put competitive pressure on more schools to offer ISAs as well. That said, students and educators acknowledge that ISAs aren't right for everyone.

"If you are going into a six-figure job right after school, a traditional loan would likely be better," says Hoyler.

Purdue presents students with comparisons showing how much they could expect to pay under an ISA versus a loan, allowing them to decide which financial instrument is right for them. According to Cartwright, the school has funded more than 1,200 ISA contracts so far.

"Our program is not a substitute for federal student loans," says Cartwright. "We are targeting students who have exhausted their grants, scholarships, and federal student loans and who might otherwise need a parent to take on a Parent PLUS loan or go to the private loan market."

Indeed, most proponents of ISAs see it as unlikely, at least for now, that the agreements become the dominant vehicle for financing education. For one thing, federal student loans, unlike privately offered ISAs, are federally subsidized. But for students who don't qualify for such loans or have exhausted them, ISAs may be an attractive alternative. Others, like Palacios, also welcome the fact that Friedman's original idea has influenced the federal loan system through the introduction of income-based repayment.

"The other component from ISAs that I think government loans should incorporate is the idea that someone should have skin in the game when it comes to how students perform after leaving school," says Palacios.

Wherever ISAs go from here, they have already sparked bipartisan interest in looking at ways to offer better financial protections for students and incentives for educators as well as expanding access to higher education and skills training, which are increasingly in demand today.

Readings

Bair, Sheila, and Preston Cooper. "The Future of Income-Share Agreements." Manhattan Institute Report, March 2019.

Friedman, Milton. "The Role of Government in Education." In Robert A. Solo (ed.), Economics and the Public Interest. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1955.

Palacios, Miguel. "Financing Human Capital through Income-Contingent Agreements." In Stuart Andreason, Todd Greene, Heath Prince, and Carl E. Van Horn (eds.), Investing in America’s Workforce: Improving Outcomes for Workers and Employers. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2018.

Ritter, Dubravka, and Douglas Webber. "Modern Income-Share Agreements in Postsecondary Education: Features, Theory, Applications." Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Discussion Paper No. 19-06, December 2019.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.