Medical Spending in Old Age

Older Americans' health care spending is relevant to many policy questions. Recent research shows that spending varies considerably with income, as do funding sources for that spending. Overall, the government pays more for lower-income individuals than higher-income individuals, but Medicaid is not just a program for the young and the poor. It provides substantial benefits to older adults with higher incomes as well.

Health care spending in the United States is an issue of considerable interest to both policymakers and the public. The spending of people over age 65 is of special concern given their growing share of the population and the portion of their health expenses paid for by the government. In 2010, average medical expenditures of people over 65 were more than 2.6 times the national average. They accounted for one-third of total medical spending but only 13 percent of the population. The government paid for about 67 percent of older adults' health care. As their share of the population continues to grow, the fiscal impact is almost certain to increase.1

As policymakers consider reforms to programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, and to the health care system more broadly, it will be important to understand the medical expense risk that these programs are intended to offset, the extent to which the programs offset the risk, the amount of expenditures associated with these programs, and the value that older adults attach to these expenditures. In recent research, one of the authors of this brief (Jones) has documented key facts about medical spending after age 65 in an effort to answer these questions.

The Distribution of Spending

In a 2016 article with Mariacristina De Nardi of the Chicago Fed and Eric French and Jeremy McCauley of University College London, Jones analyzed data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) for the years 1996 through 2010.2 Jones and his coauthors examined the distribution of medical expenses among older individuals, considering both total spending and spending disaggregated by type of treatment and by payer. They found that total spending is highly concentrated; individuals in the top 5 percent of the expenditure distribution spent an average of nearly $98,000 per year, compared with the overall average of about $14,000, and constituted nearly 35 percent of all medical spending. Those in the top 5 percent of the expenditure distribution also spent significantly more out of pocket: almost $27,000 apiece versus the overall average of $2,740. They accounted for 49 percent of all out-of-pocket spending.

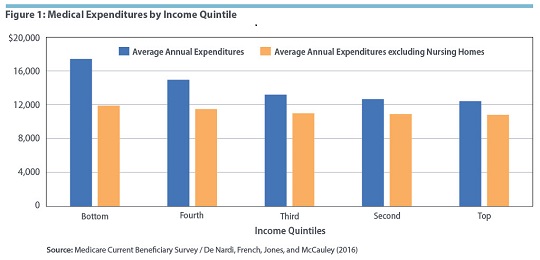

Medical spending varied considerably with income. Annually, individuals with lower incomes consumed more medical resources than those with higher incomes; total annual spending for older adults in the bottom income quintile averaged $17,410, while it averaged $12,430 for older adults in the top income quintile.3

Over a lifetime, at least some of this annual spending difference is likely to be offset by the longer lifespans, on average, of higher-income individuals. Year-to-year, much of the difference is explained by the fact that lower-income individuals consumed more nursing home care than those with higher incomes. (Because those with lower incomes tend to be sicker, they are more likely to enter a nursing home at the beginning of a sample period. People with high incomes are in fact slightly more likely to enter nursing homes overall, but they enter them later in life.4) Excluding nursing homes, the difference in average expenditures between the bottom and top income quintiles was only about $1,100. (See Figure 1.)

How Do Older Adults Pay for Health Care?

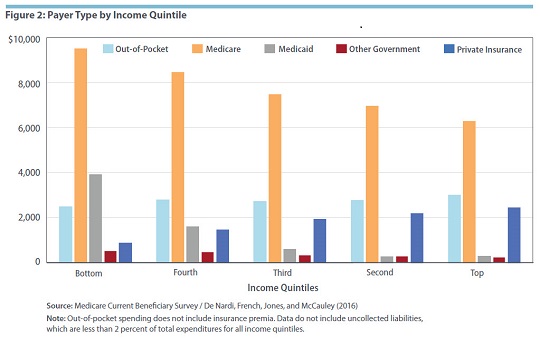

Virtually all people older than 65 in the United States are eligible for Medicare, which includes both original Medicare, where Medicare pays providers directly, and Medicare Advantage, where Medicare contracts with private insurance companies to provide coverage. The plans have different coverage rates: original Medicare pays for the great majority of the cost of short-term hospital stays, 80 percent of the cost of doctor visits, and, since 2006, most of the costs associated with prescription drugs (with an additional premium). Medicare Advantage plans pay for close to 100 percent of the cost of hospital stays, doctor visits, and prescription drugs. De Nardi, French, Jones, and McCauley found that Medicare and Medicare Advantage together paid for 54.7 percent of older adults' health care during the period they studied.

Some individuals also have private insurance plans, such as Medigap or employer-sponsored retiree benefits, that can help cover expenses not paid for by Medicare. Private insurance covered 12.5 percent of older adults' health care expenses. But neither Medicare nor most private plans cover long-term nursing home care, the median cost of which exceeds $80,000 per year.5 Researchers have estimated that U.S. adults face a 30 percent probability of spending at least 100 days in a nursing home; the average length of such stays is more than three years, at a cumulative out-of-pocket cost of more than $200,000.6 Many of these expenses are covered by Medicaid, which pays nearly all of the cost of nursing home care for low-income older adults and assists higher-income individuals who have exhausted their savings. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid assists 64 percent of nursing home residents, making it an important public insurance program for older adults. Jones and his coauthors found that Medicaid covered 9.4 percent of total health care spending. Including both Medicare and Medicaid, the government spent close to $14,000 per year on older adults in the bottom income quintile and slightly more than $6,540 on those in the top quintile. (See Figure 2.) Much of the difference is explained by the large portion of Medicaid spending that goes to nursing homes.

Many researchers have shown that higher-income people spend more out of pocket across all types of medical care than those with lower incomes. But if private insurance premiums are excluded, annual out-of-pocket spending is roughly equal across the income distribution, according to Jones and his coauthors.

Who Gets Medicaid?

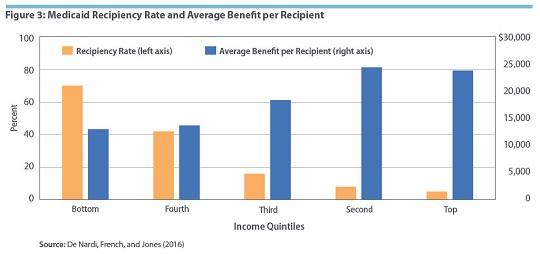

In another 2016 article, De Nardi, French, and Jones studied Medicaid spending in more detail, using data from the MCBS from 1996 through 2010 and the 1994–2010 waves of the Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old (AHEAD), a survey conducted by the University of Michigan.7 The authors compared Medicaid recipiency rates and Medicaid spending by permanent income quintile for single retirees, a group that is particularly easy to analyze.8

As stated above, Medicaid assists both low-income individuals and higher-income individuals who have exhausted their savings. Individuals in the first group, who qualify for Medicaid even if their medical expenses are small, are known as the "categorically needy." Individuals in the second group, who qualify only after their expenses exceed their financial resources, are known as the "medically needy." Not surprisingly, 70 percent of retirees in the bottom quintile — the categorically needy — received Medicaid benefits, compared with just 5 percent of those in the top quintile. However, higher-income individuals received significantly higher average Medicaid benefits: $23,790 per year for older adults in the top income quintile versus $12,990 per year for those in the bottom quintile. (See Figure 3.) Because richer people qualify for Medicaid only after they exhaust their savings, richer Medicaid recipients are more likely to face catastrophic medical expenses.

For lower-income retirees, Medicaid recipiency was fairly stable over retirement. But recipiency rates rose rapidly with age for those in higher quintiles. For example, in the oldest survey cohort the authors studied, the share of people in the top two quintiles receiving Medicaid was 4 percent at age 89; it increased to 20 percent by age 96. As this illustrates, even older adults with relatively substantial resources can face medical shocks large enough to drain their assets and qualify them for Medicaid.

In line with these findings, higher-income individuals also faced a greater risk of increasing out-of-pocket spending (including insurance premia). Out-of-pocket spending rose substantially with age, especially for those in the top quintile; lower-income people, who were categorically protected by Medicaid, spent less out of pocket.

The Value of Medicaid

De Nardi, French, and Jones developed a model to calculate how older adults value medical versus nonmedical consumption, and thus how they value Medicaid benefits. They found that the present discounted value of medical consumption (that is, the current value of expected future spending) was higher than the value of nonmedical consumption for individuals in the bottom permanent income quintile, while the opposite was true for those in the top quintile. The value of both types of consumption, however, was much higher for the rich than for the poor. The present discounted value of nonmedical consumption was $59,200 for the bottom quintile and $234,900 for the top quintile. The value of medical consumption was $108,300 for the bottom quintile and $229,700 for the top quintile.

Overall, richer retirees in the model paid more in Medicaid taxes than they expected to receive in Medicaid benefits, while poorer individuals paid much less. Those in the top quintile paid $4.59 in taxes for every $1 in expected benefits, while those in the bottom quintile paid just 20 cents per dollar of expected benefit.

Still, richer individuals seem to value Medicaid quite highly. The authors simulated various reforms to Medicaid and calculated the payment an older adult would need to receive (known as the compensating variation) in order to be as well off after the reform as before it. When Jones and his coauthors made the program less generous, they found that the compensating variation for people in the bottom three income quintiles was between $1,000 and $1,800 greater than the reduction in the present discounted value of Medicaid payments. But for people in the top quintile, the compensating variation was $3,000 more than the reduction in payments. Similarly, when the authors made Medicaid more generous, older adults in the bottom two quintiles valued the increase in benefits at less than its cost, while those in the top quintile valued the increase at twice its cost.

There are two primary reasons why richer individuals might place a higher insurance value on Medicaid. First, they have a higher level of consumption to begin with, and thus have more consumption to insure in the years before they enter a nursing home. Second, they face a greater risk than poorer individuals of living longer than their life expectancy and thus incurring very high medical costs late in their lives.

The picture changed somewhat when taxes were taken into consideration. Even though older adults with higher incomes valued each dollar of increased benefits at twice the cost, this value was still less than the additional taxes they would have to pay to fund the extra benefits. Older adults with lower incomes, who placed less value on increased benefits, still favored more generous benefits since their tax burden would increase by far less than the value. Overall, the authors concluded that the current Medicaid system appears to be about the right size for single retirees, meaning that the value older adults place on the benefits is about the same as the benefits themselves.

Conclusion

Several key facts emerge from Jones' and his coauthors' studies of older adults' medical spending. Spending is highly concentrated at the top of the spending distribution. Lower-income people spend more annually and have more of their spending covered by the government than higher-income people. Much of the difference is the result of higher nursing home expenditures, which are largely covered by Medicaid. However, older adults with relatively high incomes also can become eligible for Medicaid after they exhaust their savings. As a result, high-income people tend to value Medicaid at more than its actuarial cost because it allows them to consume more in their golden years without worrying about potential nursing home expenses down the road. Even so, the value that high-income single retirees would place on increased Medicaid benefits would be less than any associated increase in their taxes.

In short, medical spending constitutes a significant financial risk for older Americans, and Medicaid, generally thought of as a program for the young and the poor, provides significant benefits to older adults with high incomes as well.

John Bailey Jones is a senior economist and research advisor and Jessie Romero is an economics writer in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The Census Bureau estimates that the share of the population older than 65 will increase to 23.6 percent by 2060.

Mariacristina De Nardi, Eric French, John Bailey Jones, and Jeremy McCauley, "Medical Spending of the U.S. Elderly," Fiscal Studies, September-December 2016, vol. 37, no. 3-4, pp. 717–747.

Individuals in the bottom quintile had an average annual income of $8,000. Those in the top quintile had an average annual income of $68,930. The MCBS measures total household income during the past twelve months, including transfer and asset income.

See Table 3 in Mariacristina De Nardi, Eric French, and John Bailey Jones, "Medicaid Insurance in Old Age," American Economic Review, November 2016, vol. 106, no. 11, pp. 3480–3520. A working paper version![]() is available online.

is available online.

Medicare will help pay for up to 100 days in a skilled nursing facility under certain conditions.

R. Anton Braun, Karen A. Kopecky, and Tatyana Koreshkova, "Old, Frail, and Uninsured: Accounting for Puzzles in the U.S. Long-Term Care Insurance Market," Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper No. 2017-3, March 2017.

De Nardi, French, and Jones (2016)

More precisely, the authors study postretirement permanent income, excluding asset income, which they find is a reasonable proxy for lifetime permanent income. Average annual income is about $5,000 in the bottom quintile and $23,000 in the top quintile.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.