College-Educated Immigrants Bolster U.S. Productivity

The United States is the largest destination in the world for college-educated immigrants, but their path to employment in this country has become increasingly difficult during the past decade, a condition that can hinder productivity growth. This brief discusses the main contributions that college-educated immigrants make to U.S. productivity growth, such as providing scarce skills that supplement and complement those of native workers, contributing disproportionately to innovation and promoting job creation in the United States by foreign-based multinational corporations.

Attracting talented foreign workers bolsters the domestic economy because immigrants bring new skills, information and knowledge that improve productivity. This brief focuses on immigration of college-educated workers to the United States during the past 20 years.

Looking at college-educated workers separately is important because the path for immigration tends to be very different for workers with college degrees, particularly in the United States. Immigrants with college degrees come to the United States predominantly through the H-1B program or other employment-based visa programs, while those without college degrees come to the country predominantly through the family reunification path. In the H-1B program, employers select and sponsor immigrants to work in the United States for three years, with the option to renew for three additional years. Once the H-1B visa expires, employers can help those immigrants obtain green cards that allow them to continue working in the United States. But the number of employment-based visas awarded each year is capped, and when the number of applicants exceeds the cap, the United States allocates the visas through a lottery among all applicants. Both the visa cap and the lottery system have generated intense policy discussions in recent years.

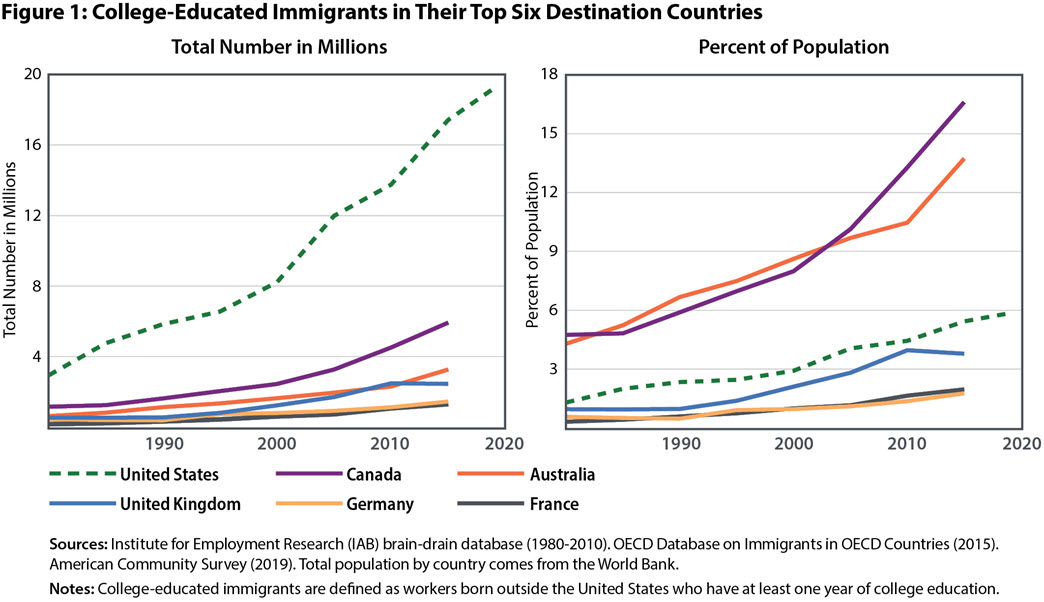

The left panel of Figure 1 shows that the United States is the main destination in the world for immigrants with at least one year of college education. The total number was larger than the next five nations combined in 2015, and immigrants with some college education represented 45 percent of all immigrants in the United States by 2019. However, when looking at the numbers relative to total population, the story is substantially different.

The right panel of Figure 1 shows that immigrants with college educations accounted for more than 13 percent of Australia's population and more than 16 percent of Canada's population in 2015. Both countries' immigration polices heavily favor skilled workers. The United States ranks closer to the United Kingdom, with college-educated immigrants comprising slightly more than 5 percent of the population in 2015.

Countries such as Australia and Canada seem to place higher value on the economic contributions of college-educated immigrants. These contributions fall into three main categories. One, immigrants increase productivity by bringing scarce skills that supplement and complement the skills of native workers. Two, immigrants contribute disproportionately to innovation. And three, foreign firms who want to invest in the United States benefit from home-country immigrants who can reduce communication and cultural barriers. Economic research overwhelmingly concludes that these benefits exceed any costs imposed on native workers and that the United States could benefit from reforming the process for granting work visas.

See Giovanni Peri and Chad Sparber, "Task Specialization, Immigration, and Wages," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, July 2009, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 135–169; also, see Peri and Sparber, "Highly-Educated Immigrants and Native Occupational Choice," Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, July 2011, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 385–411.

Jennifer Hunt and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle, "How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?" American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, April 2010, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 31–56.

Shai Bernstein, Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade and Beatriz Pousada, "The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States," Manuscript, July 2019.

Konrad B. Burchardi, Thomas Chaney and Tarek A. Hassan, "Migrants, Ancestors and Foreign Investments," Review of Economic Studies, July 2019, vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 1448–1486.

Nicolas Morales, "High-Skill Migration, Multinational Companies, and the Location of Economic Activity," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper No. 19-20, December 2019.

See William R. Kerr and William F. Lincoln, "The Supply Side of Innovation: H‐1B Visa Reforms and U.S. Ethnic Invention," Journal of Labor Economics, July 2010, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 473–508; also, see Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih and Chad Sparber, "STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in U.S. Cities," Journal of Labor Economics, July 2015, vol. 33, no. S1, part 2, pp. S225–S255.

William R. Kerr, "Global Talent and U.S. Immigration Policy," Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 20-107, April 2020.

Many nonprofit employers, such as government agencies and most colleges and universities, are exempt from the cap.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.