The Shortcomings of a Work-Biased Welfare System

The recently passed American Rescue Plan Act has once again brought attention to the U.S. welfare system. This EB provides an overview of the welfare system — including recent changes — and assesses the system's effectiveness in achieving its goals. The brief highlights a "work bias" that is embedded in many U.S. welfare programs and has both intended and unintended effects on the system's ability to combat poverty.

All advanced economies have implemented safety net programs with the goal of ensuring that basic standards of living are met for everyone. These safety net programs — collectively known as welfare systems — strive to put floors on how low individuals' consumption and well-being can go.

While opinions differ regarding the size and nature of welfare systems, most agree that any redistribution should be accomplished as efficiently and equitably as possible. Naturally, then, changes to how transfers are determined and carried out attract the public's attention.

The U.S. welfare system includes a broad variety of means-tested programs aimed at reducing poverty by providing government-sponsored benefits to eligible individuals and families. While these programs have helped shrink poverty dramatically in the U.S., it has not been eliminated. Currently, one out of every six Americans is poor according to the U.S. government's official definition of poverty, meaning they earn less than $12,880 per year.1

Poverty has negative consequences that are both long lasting and far reaching. There is good evidence of long-lasting harm to people — especially children — when they undergo even short, temporary stints in poverty.2

In addition, poverty affects a larger number of people than the poor themselves, because it is often associated with drug abuse, mental health issues, involvement in the criminal justice system, increased incidence of divorce, and teen and out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Negative effects on societal well-being that surpass the damage done directly to the affected individuals are called "negative externalities" by economists. Because these externalities are generally significant, they provide additional incentives for societies to provide welfare assistance — incentives that supplement more altruistic motives such as empathy and moral obligation.

The U.S. Welfare System's Work Bias

The U.S. is rather unique among industrialized nations in the modest magnitude of its welfare system. For instance, the U.S. is the only advanced economy that does not have universal health care.

In a uniquely American way, the debate over welfare is a debate not just about fighting poverty, but also about worthiness, fairness and work ethics. Though the system has a purported goal of alleviating poverty, the goal is often framed within the context of encouraging work and disincentivizing dependence on the system itself. Thus, the focus shifts from helping the poor to helping the working poor. The U.S. welfare system's "work bias" is embodied in stringent work requirements for welfare recipients and a distinct dearth of support for able-bodied, non-elderly, jobless individuals.

The U.S. has a deep-seated tension between the concept of a safety net and the concept of self-reliance. America is considered by many to be "the land of opportunity," and the welfare system's work bias reflects the assumption that such opportunities are there for those who work hard enough.

However, the very existence of a welfare system implicitly recognizes that some may need extra help from the government, as they may not be able to gain access to such opportunities otherwise, regardless of effort. The recent economic recession — induced by the COVID-19 pandemic — has put into stark relief the consequences of connecting support to the poor to their ability to work and has challenged the previously wide consensus on a welfare system that supplements the poor's consumption conditional on them working or looking for work. This represents, perhaps, one of the most momentous shifts in the public perception of the welfare system since the mid-1990s reforms.

The Main Parts of the U.S. Welfare System

The current U.S. welfare system is rather complex. There are two main types of programs: tax credits, and benefits for poor households in the form of cash assistance or in-kind transfers.

The main benefits programs are:

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), more commonly known as food stamps

- Subsidized housing programs, which defray housing costs

- Medicaid and CHIP, which provide health care assistance to poor adults and children

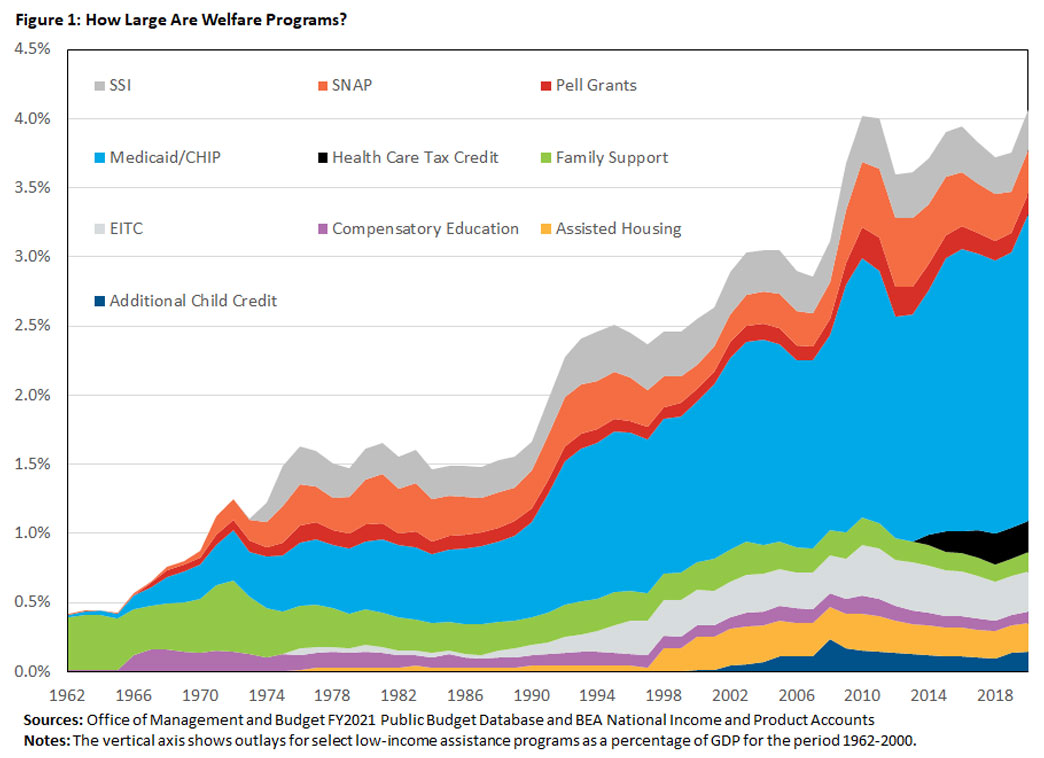

The health care programs are by far the largest and fastest growing, accounting for well over a quarter of the federal government's budget and 5 percent of GDP. (See figure 1 below.)

Benefits programs are mostly in-kind in nature: They provide food, housing or medical services. The only program not entirely in-kind is TANF. About one-third of TANF's budget is spent on cash transfers, while the other two-thirds fund a diverse array of services to boost job readiness for recipients.

Most of the benefits programs have stringent work requirements and are targeted to parents, so they are typically greatly reduced or not available to poor individuals who do not work or do not have children. For example, a single mother with two children between 5 and 18 years old needs to work at least 30 hours a week to be eligible for TANF. This requirement drops to 20 hours a week if one of the children is under 5 years old. Similar work requirements are in place for housing assistance, while SNAP and Medicaid are nearly universal.

Tax credits are another large part of the welfare system. The earned income tax credit, or EITC, is an annual refund on a family's tax obligations. It is only available to those with some work earnings and is much more generous to parents than non-parents or parents whose children do not live with them. For example, in 2018, the average EITC was $3,191 for a family with children, compared with just $298 for a family without children.

EITC refunds increase with income earned for very poor households before plateauing and eventually tapering off as households continue to increase their income. This structure is both cost-effective and successful in diverting more funds to households who need them most while incentivizing work. (This is because the credit grows as income grows for the poorest households.) This flexible structure has made the EITC — and its sister program the child tax credit, or CTC — very popular.

Economists also favor tax credits because the funds from the program can be used by households to purchase goods and services as they see fit, thus enabling poor households to supplement their consumptions in an unconstrained way, while other programs such as SNAP or TANF provide funds for specific goods and services only.

The EITC and CTC have been historically very successful at lifting parents and their children above the poverty line. This is because they both encourage parents to work more — the more they earn, the more they get back in tax credits (up to a certain threshold) — and directly provide cash to families that they can spend however they like.

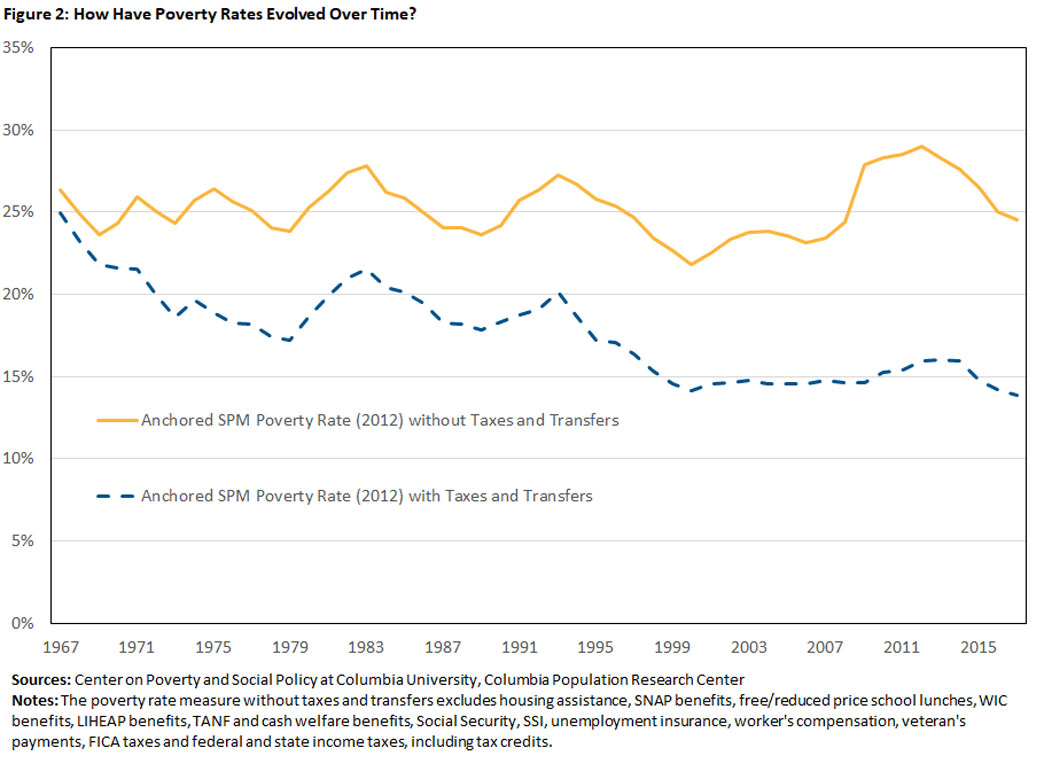

Indeed, if we include public transfers and tax credits when calculating the poverty rate, the after-transfer poverty rate went from 25 percent in the 1970s to approximately 15 percent currently. (See the dashed line in figure 2 below.)

Should we then interpret this figure as portraying a successful welfare system? Yes and no. It is true that the welfare system has been successful in supplementing the incomes of the poor and lifting them above the poverty line.

However, one also sees from figure 2 that the poverty rate excluding public support (solid line in figure 2) is remarkably flat over time: It currently stands at about 25 percent, as did in the 1970s. This means the ability of the poor to sustain a higher level of income independently of transfers has not changed over time.

I conclude that the welfare system has not been successful in lifting people out of poverty in a permanent way. Simplifying somewhat, we could say that it is a system that brings people out of poverty, but not up the income distribution. Despite its emphasis on self-reliance, the current structure of welfare programs has done little to foster independence and long-term income growth for poorer households. If it had, we would see the pre-transfer poverty level drop as fewer families would rely on public transfers to avoid poverty. This is unfortunately not the case.

Welfare support is relatively meager. As mentioned earlier, a single mother with two young children needs to work at least 30 hours to qualify for TANF. Even then, though, benefits are typically a small fraction of a state's median income. For example, a single mother with two children is eligible for a monthly benefit of $170 in Mississippi and a little over $1,000 in New Hampshire. The latter may seem large but is only 1.3 percent of New Hampshire's median income (and Mississippi's benefits are only 0.4 percent of that state's median income).

Although these transfers may avoid abject misery, they are hardly sufficient to purchase high-quality child care, safe and reliable housing and transportation, education and training, or health services — investments in welfare recipients' human capital that could improve their long-term earnings prospects and lower poorer families' reliance on welfare transfers to escape poverty.

The Benefits Cliff

There is also another aspect of the welfare system that hinders long-term income growth and sustained well-being for poorer families: benefits cliffs. As individuals improve their income levels, most benefit programs reduce assistance until this amount abruptly becomes zero after a pre-specified income threshold. At that point, an extra dollar earned is exceeded by the loss of benefits, resulting in net disposable income decreasing even as labor income increases.

Understandably, people facing benefits cliffs tend to turn down better-paying jobs to keep their income steady. Benefits cliffs are particularly steep for tax credits, but they are also present in all other programs.

For example, suppose that the single mother in our previous example works and qualifies for assistance (both cash and in-kind) of $1,000 per month. Let's further suppose she gets promoted to a job that pays an additional $500 per month, and this increase brings her income above the eligibility criterion for assistance. She gains $500 in labor income but loses $1,000 in benefits. So, even though she was promoted to a better-paying job, her income goes down.

Welfare, Recessions and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Another shortcoming of the current safety net structure is that the welfare system is not highly responsive to the economic cycle, making it largely unable to respond to higher poverty rates during recessions. This aspect is a direct expression of the work bias that informs the safety net: Most programs have work requirements, so people who are out of work are not eligible.

But recessions are precisely when people become poor due to losing their jobs. SNAP is a partial exception because it is available to jobless individuals, though assistance to those without dependent children is still limited, thus the reach of the program during economic downturns is far from universal.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light how inadequate the safety net was, especially for the most vulnerable: children. The pandemic has affected a large number of individuals and families, swelling the poverty rate; some estimates put it back at the 1970s level of 25 percent.3

The American Rescue Plan Act

This has made poverty more visible to many Americans who were previously unaffected by it. Though this is not the focus of this Economic Brief, we would be remiss not to notice how the COVID-19 pandemic amplified the interactions between poverty and racial inequality and prompted a debate on whether the welfare system can address this interplay, or the root causes of poverty. COVID-19 has also interrupted the upward trajectories of many families who had managed to climb the income ladder and reach the middle class. The American Rescue Plan Act that Congress recently passed attempts to address these unique circumstances.

The bill has two main components. First, it makes direct payments to individuals to cope with the effects of the pandemic and related severe economic downturn. Direct payments are almost universal. Thus, they are not addressed to combat persistent poverty but rather to relieve the temporary economic distress brought about by the pandemic.

Second, the bill reforms the safety net paradigm to better support working families with children. These provisions are more directly related to our discussion of the welfare system. These reforms include significantly expanding the size and scope of the EITC, CTC and the child and dependent care tax credit. These new benefits do not taper off with the number of children in households — unlike most other welfare programs — and have significantly higher income thresholds to alleviate the impact of benefits cliffs on low and middle earners.

These provisions plausibly signal a profound change in how voters — and the legislators they elect — envision the welfare system and its role in supporting families and children of lesser means. They recognize that we all have a vested interest in healthy, thriving children. Investing in children has high returns not just for individuals but also for society as a whole and, thus, is a worthy cause to spend public money on.

Though some of these provisions are slated to expire after one year and some after five years, I believe that the benefits from making them permanent would be substantial. My hope is that there is clear political will to consider such changes in a permanent way. Overall, both public opinion and policymakers have come to view a European-style safety net on American soil more favorably than ever before. I regard this as a momentous shift of the public opinion and a precious opportunity to reflect on what policies, programs and public interventions may lead more of us to share more broadly in the wealth our economy creates.

Claudia Macaluso is an economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

"2021 Poverty Guidelines," Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Jan. 26, 2021.

Hilary W. Hoynes and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, "Safety Net Investments in Children," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, March 8, 2018.

Zachary Parolin and Megan A. Curran, "Monthly Poverty Rate Declines to 13.2% in the United States in January 2021 (PDF)," Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University, March 4, 2021.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.