The Pandemic, Child Care and Women’s Labor Force Participation

The pandemic has changed how households work, spend and care for children. In this Economic Brief, we highlight economic research that examines the patterns seen in women's work experiences in particular. We look at both the pandemic and, more generally, how shocks to the economy affect women's work decisions. Throughout, we will try to connect what we observe to households' broader economic environments and will emphasize — in the case of the pandemic — the role of away-from-home child care.

This article was updated to reflect that the labor force participation rate for women without a bachelor's degree remains 4.0 percent (not 2.0 percent) below its pre-pandemic level.

The pandemic and subsequent policy response had plausibly significant impact on households' labor market and home production decisions. In this article, we'll look specifically at the impact on the labor force participation (LFP) of women.

The Pandemic-Driven Decline in Female Labor Force Participation

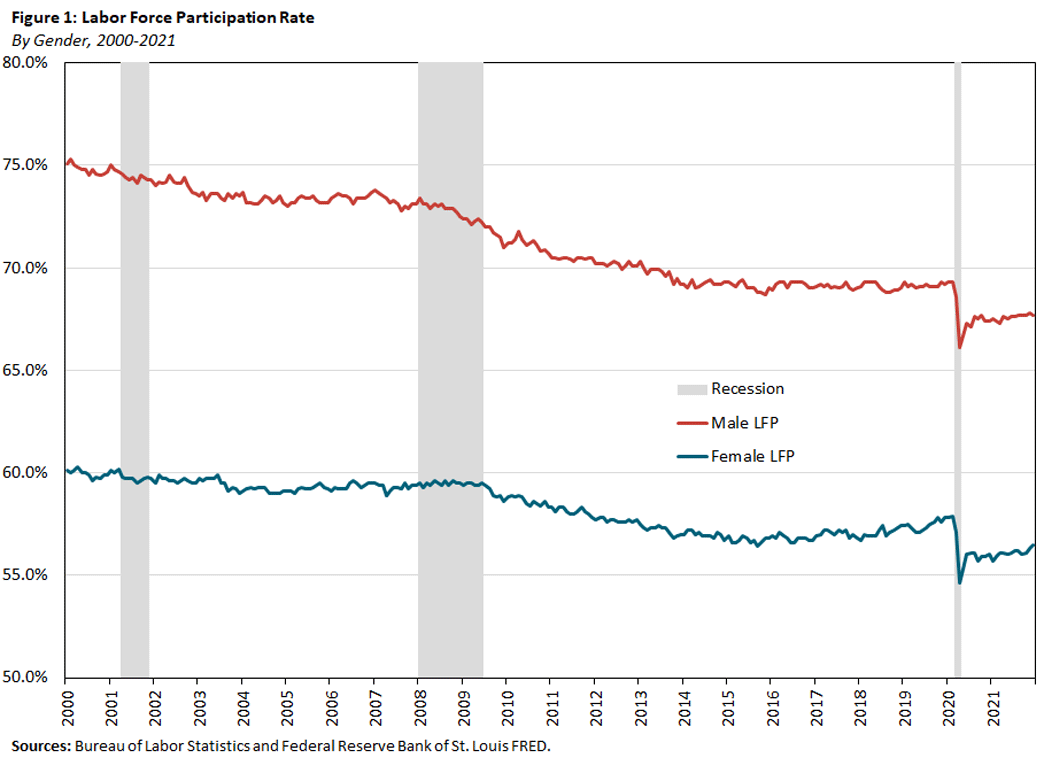

From March to April 2020, women's LFP fell 2.5 percentage points. While much of the initial drop recovered quickly, it still remains notably below the rate prior to the pandemic, as seen in Figure 1.

Men's LFP also declined significantly between March and April 2020, but the drop in women's LFP was notable because it differed from the pattern seen during previous recessions. As the figure shows, while men's LFP dropped during the 2001 and 2007-2009 recessions, women's LFP stayed relatively level.

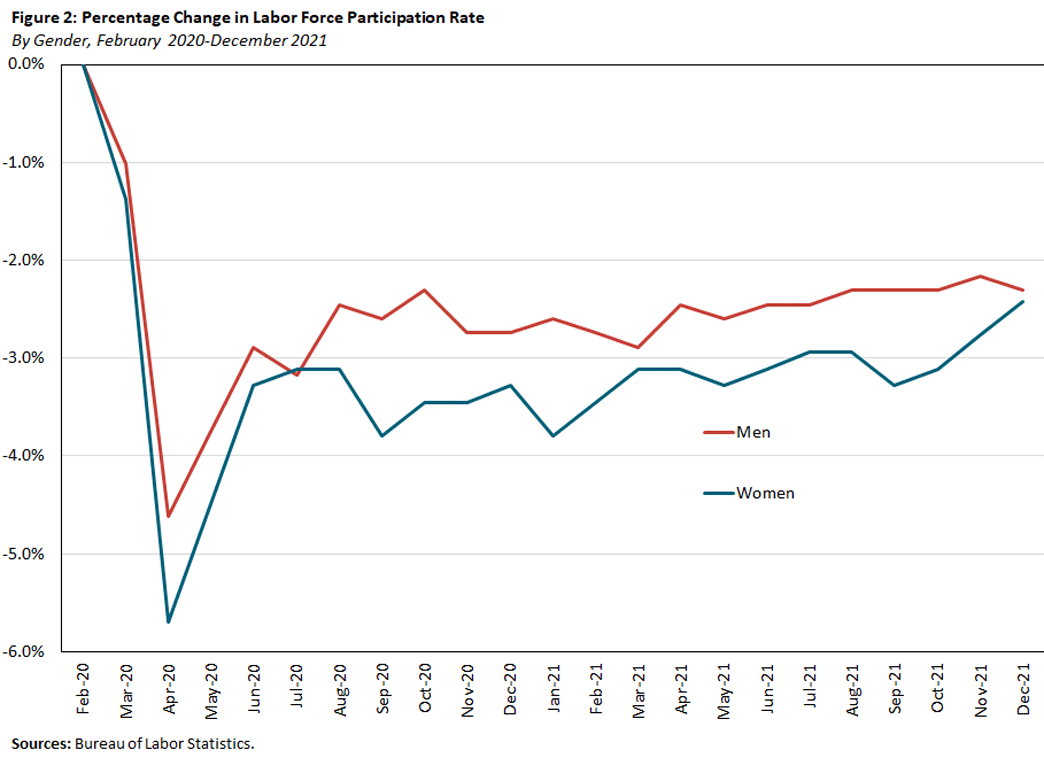

While LFP rates for both men and women have not returned to pre-pandemic levels, women's return to the labor force has remained slightly suppressed relative to men for the duration of 2020 and throughout 2021, as seen in Figure 2.

Economists have long been interested in how participation varies in booms and recessions, including along gender lines. According to the 2005 paper "The Business Cycle and the Life Cycle," the previous patterns might be partially explained by the fact that, historically, workers in goods-producing industries tend to have more volatile hours than service-sector workers, and women are less likely than men to work in goods-producing occupations. Thus, women were less apt than men to lose their jobs during a typical recession, also making them less likely to completely lose their attachment to the labor force. The pandemic-induced recession, however, disproportionately hit the service sector.

But while this could potentially explain a drop in employment, it doesn't necessarily explain why women would leave the workforce altogether, as seen in women's reduced LFP. However, the pandemic also had a significant impact on another factor that may be playing a role: child care.

Child Care and Shocks

In addition to its effects on the service sector, the pandemic recession also differed from a typical recession in that it meant the forced closure of businesses and other institutions that provided a key complement to facilitating work: the care and educating of children. When state governments issued stay-at-home orders and schools switched to remote learning in March 2020, at-home child care became necessary, and the amount of time families needed to fulfill household responsibilities increased. One interpretation of the data is that families often adjusted the time of mothers away from paid work and towards child care and education.

Of course, parents with young children have always been at risk of encountering minor shocks, such as temporary lack of access due to a sick caregiver or a sick child. In these circumstances, households will face strong incentives to place the burden of adjustment on the parent with the more "flexible" job. Furthermore, if one parent is more efficient at caregiving and educating, this also creates incentives for them to opt for more flexible roles to begin with.

In the literature, we also see that the effects of both major and minor shocks vary considerably depending on family structure and education levels. Of note:

- While college-educated persons could lose a greater amount of income if a shock prohibits them from working at all, they are far less likely to lose their jobs in recessions, a point developed in more detail in the 2016 report "America's Divided Recovery."

- College-educated couples are more likely to be able to work remotely when shocks occur, compared with couples with less than a college education, as noted in the 2021 article "Educational Attainment, Employment and Working From Home, February-May 2021." Couples with less than a college education are thus more likely to be at risk of one member losing hours and income as shocks arise and are less able to manage them via alternative work arrangements.

- Single parents — who tend disproportionately to be low wage, as discussed in the 2020 report "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020" — are most vulnerable of all, having no within-household buffer.

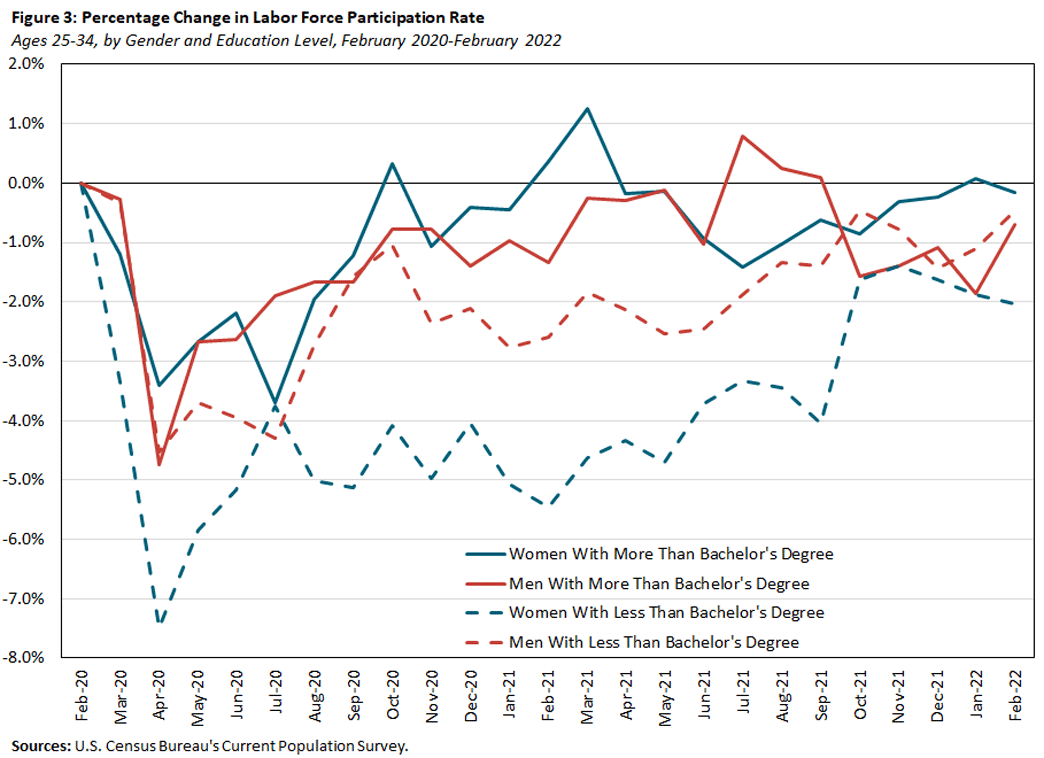

These facts could help explain why those with less formal education, especially women, were affected most strongly by the pandemic, as seen in Figure 3. For women without a bachelor's degree, LFP declined 7.5 percentage points in March/April 2020 and remains 2.0 points below its pre-pandemic level.

The Increasing Costs of Child Care

Child care can be costly to outsource (in any time, not just during a pandemic), because it is inherently a labor-intensive process. If the average level of wages and overhead expenses go up, so too will the cost of providing child care, barring technological or organizational innovations that allow fewer people to provide more care.

In the pandemic, these costs rose, due in part to a reduced supply of caregivers and an increase in marginal cost of providing services due to COVID precautions.1

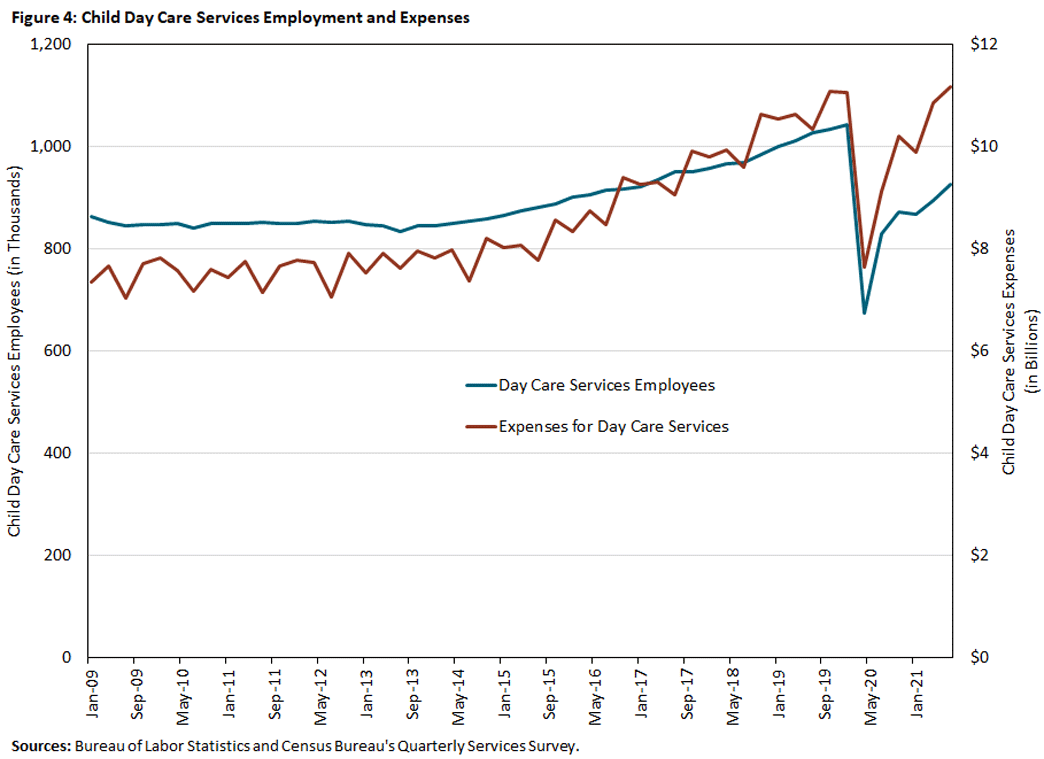

As seen in Figure 4, child day care employment has not returned to pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, the overall cost of providing care has increased at a faster rate than employment, meaning the cost per worker has increased. This will mean that some (in the data, mothers most often) will find it more cost effective to provide child care themselves and forgo market work altogether.

Such a scenario will likely affect less-educated women most, who typically earn less than their more-educated counterparts. Child care might consume most (or even all) of what they would earn — making the benefits of working in the marketplace too small to justify these high costs.

Regarding families with school-aged children, families with bachelor's degree holders are more typically able to afford to send their children to private schools, which generally resumed in-person instruction sooner than public schools. This may have enabled women with more education to continue working or to return to work sooner, though the effects are not known with certainty. On the other hand, because people tend to partner with others at their same education level, women with bachelor's degrees may also have partners who can support the family if they choose to stay home and provide one-on-one caregiving.

Increasing Resilience in the Labor Force

In her 2021 book "Career and Family: Women's Century-Long Journey Toward Equity," economist Claudia Goldin describes the COVID-19 recession as "the first major economic downturn during which the care sector will determine the fate of the economic sector." And the effects on women's labor force participation could reverberate long past this business cycle.

Being out of the labor market not only reduces the income of women directly, but it also reduces overall economic productivity as skills depreciate. And given that the share of women with bachelor's degrees has been growing relative to that of men, the cost associated with women being out of the labor force is only growing.

Parents (especially those with young children) must scramble when child care options become scarce. And when that time comes, women appear to do more of it. As a result, any reduction in connection to the workforce is immediate and potentially supports a "vicious cycle" of expectations. Namely, if employers expect women to leave at higher rates when shocks occur, they may pull back from investing in their female workforce now. Yet that only blunts the incentive of women to invest in their own career paths, which then makes it more likely that they will — yet again — be the ones who "flex" as future disruptions occur.

Thus, so long as the expectations loop is at all in play, society as a whole loses. Yet, this dismal possibility may mean that policymakers have an opportunity for a win-win. One option for supporting women's connection to the labor force is universal child care credits — conditional on maternal work. These could increase LFP — with the largest effect at the bottom of the skill distribution in the short run — and change women's career pathway decisions in the long run.

However, universal programs are expensive. In many cases, then, means-tested policies appear realistic and can allow cost-effective gains to recipients and society, as argued in the 2021 paper "Child-Related Transfers, Household Labor Supply and Welfare."

Regardless of what policymakers choose, resilient child care and flexible workplace environments will likely allow society to better realize the full marketplace potential of the female labor force.

Kartik Athreya is director of research and Sierra Latham is a senior research analyst in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

As seen in the 2020 article "The True Cost of Providing Safe Child Care During the Coronavirus Pandemic."

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Athreya, Kartik; and Latham, Sierra. (May 2022) "The Pandemic, Child Care and Women's Labor Force Participation." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 22-16.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.