Casinos and Regional Economies: Has the Game Changed?

With casinos much more common across the nation than they were a generation ago, how might the development of a new casino impact its surrounding regional economy? We survey the literature on the local impact of casinos from a variety of economic and social perspectives. We find that, despite tax revenues being a major motivator for state legalization of casinos, there is little evidence that they boost state taxes. We also find that the job gains from casino development are limited to those in lower density areas that lack nearby casinos.

Casinos are more common across the country now than they were a generation ago. Until the late 1980s, commercial casinos were legal in only two states: Nevada and New Jersey. As of June 2022, they were legal in over 30 states and coexist with over 500 tribal casinos nationwide. This has generated much debate about their role in regional economic development.

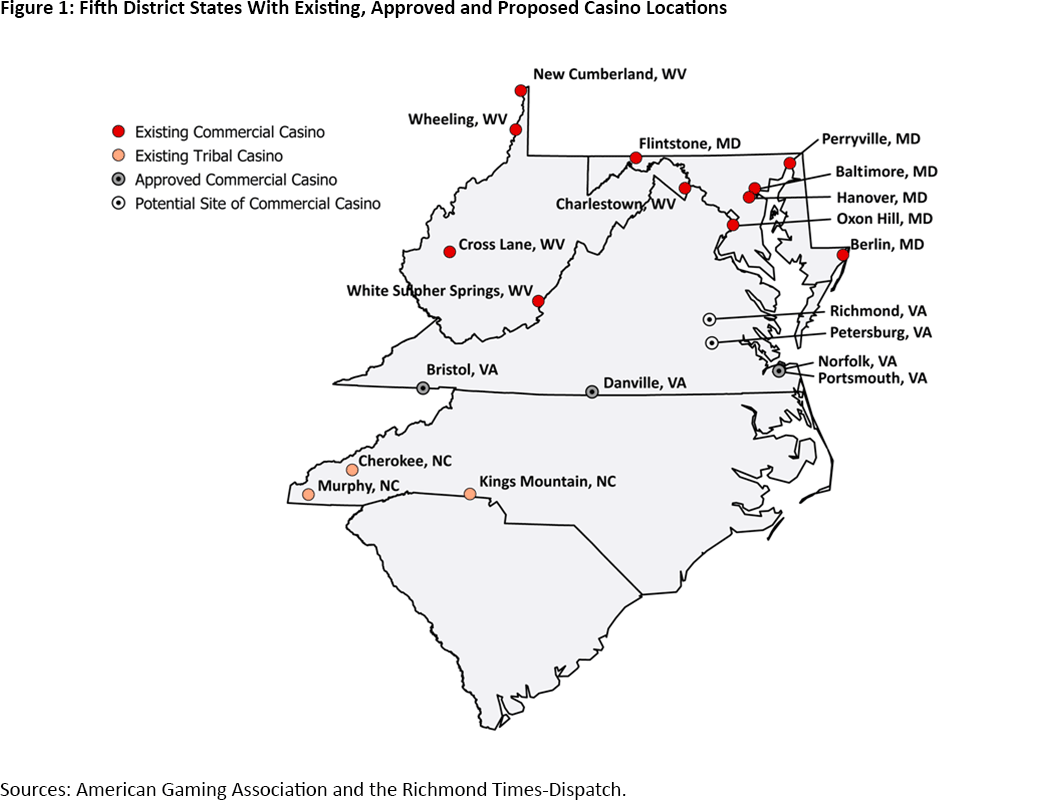

Such debate has occurred in the Fifth Federal Reserve District, where casinos are playing a potentially increasing role. The Fifth District is home to 11 operating commercial casinos (six in Maryland and five in West Virginia) and three tribal casinos (in North Carolina), which collectively employed roughly 38,000 people as of the end of 2021, according to the American Gaming Association. And in November, Virginia voters approved commercial casino development in four cities (Bristol, Danville, Norfolk and Portsmouth), while Richmond and Petersburg are potential sites for the state's fifth casino location.1

In this Economic Brief, I explore the recent history of commercial gaming in the U.S. and present evidence from the academic literature of its effects on regional economies from a variety of economic and social perspectives. The empirical evidence suggests that as commercial casinos and other gambling options have become more widespread, their ability to spur regional economic development has become more limited.

A Quick History of Modern Commercial Gaming in the U.S.

In the early 1930s, Nevada became the first state to legalize commercial casinos. It remained the only state with that distinction until New Jersey's 1976 referendum that allowed commercial casinos, limited to Atlantic City.

A major wave of casino legalization by states occurred in the late 1980s. The 1987 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians overturned state laws restricting gambling on federally recognized tribal lands. The following year, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which effectively delegated gaming regulatory powers to state governments.

As state governments managed their new regulatory duties for tribes, many states considered the legalization of commercial casinos as an economic development strategy for regions. Iowa became the third state to legalize commercial gaming in 1989, followed by several others in the early 1990s.2 Several states legalized commercial casinos from the mid-2000s through the mid-2010s,3 and improved technology enabled the introduction of online gambling in some states during this period.4

The next major historical moment for U.S. gaming occurred in 2018, when the U.S. Supreme Court broke a regional monopoly on sports gambling in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association. The court overturned the 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, which restricted state-sponsored sports betting outside of states with then-existing operations.5 As of May 2022, sports betting is legal in 35 states plus the District of Columbia.6

Casinos and Public Finance

While states have legalized casino gambling sporadically over the past 40 years, their primary motivator for casino adoption has remained consistent: tax revenues. The 2010 paper "Determinants of the Probability and Timing of Commercial Casino Legalization in the United States" finds three major drivers of commercial casino legalization in the period from 1985 to 2000:

- Addressing fiscal stress

- Keeping gambling revenues within the state

- Attracting "export taxes" from out-of-state tourists

On the surface, diversifying state tax revenue streams by adding casino gambling appears to stabilize state budgets without raising existing taxes, especially as taxes on commercial gaming are generally higher than on other goods and services. Unlike standard corporate taxes which are applied to profits, gaming taxes are typically applied to the net amount gambled. Gaming tax rates vary widely across states, with lower rates in states with more established casino markets, such as Nevada and New Jersey.

Tax revenues from gambling are often publicly earmarked for spending on "social good" programs. For example, pro-casino campaigns encouraged senior and disabled residents to vote yes on the 1976 New Jersey casino referendum, suggesting that up to 15 percent of gross gambling receipts would be used to fund programs for these groups.7 Additionally, Maryland's 2008 casino legislation established an education trust fund (PDF) to receive nearly half of the state's gaming revenue.

However, as earmarked funding is fungible, there is no guarantee that the additional revenue set aside would result in a net increase in spending for a specific social program. In other words, there is nothing stopping a state from, for example, offsetting an increase in senior program funding from a devoted revenue stream from casino taxes with a decrease from the general tax revenue stream. Even so, the 2007 paper "The Impact of Earmarked Lottery Revenue on K-12 Educational Expenditures" suggests that, while education expenditures do not increase dollar for dollar with earmarked lottery revenue, earmarked revenues have a higher probability of increasing school spending than non-earmarked revenue (when lottery taxes are deposited into the general fund).

With such an emphasis on gambling tax revenues, do commercial casinos bring in more tax revenue for states? The answer is inconclusive. The 2013 book "Casinonomics" suggests that whether legalized commercial casinos raise overall tax revenues depends on the degree of substitutability between the new casinos and any existing legal gambling options in the state (such as lotteries and horse racing) as well as non-gambling goods and services. In other words, if there is a high degree of substitutability, consumers who patronize the newly opened casinos will likely spend less both on lotteries (if available) and on other goods and services that generate state tax revenue. Therefore, net state tax revenues will depend on the difference in the changes in spending and the respective tax rates of the spending categories.

In one of the few comprehensive studies of legalized gambling on state tax revenues, the 2011 paper "The Effect of Legalized Gambling on State Government Revenue" finds that commercial casinos tend to slightly decrease state tax revenues on average due to state residents substituting their spending away from other consumer expenditures.

Casinos and Economic Development

The 40 years of casino activity in Atlantic City has made it the subject of much empirical work to understand the effects of gaming. The intention of casino development in Atlantic City was not just to boost tax revenue, but also to help redevelop the city.

A successful resort in its early 20th century heyday, Atlantic City had fallen on hard times by the 1970s. According to the 2004 book "Boardwalk of Dreams," the city's population had fallen by a quarter, widespread air travel made resort destinations in Florida more accessible to well-heeled tourists, and potential local visitors had reoriented their beach trips to more family-friendly destinations along the Jersey Shore. Being the only destination on the East Coast for legalized gambling, commercial casinos offered "a unique tool of urban redevelopment for Atlantic City" according to the amendment to the state's constitution.

However, many researchers conclude that the industry did not have a significant lasting positive impact on the city's economy, nor did it spur widespread urban development beyond the casinos themselves.8 Despite booming casino development in the 1980s, the city's central business district continued to struggle, and significant amounts of developable land remained vacant and deteriorated. To this day, the city notoriously has difficulty keeping a single grocery store open.

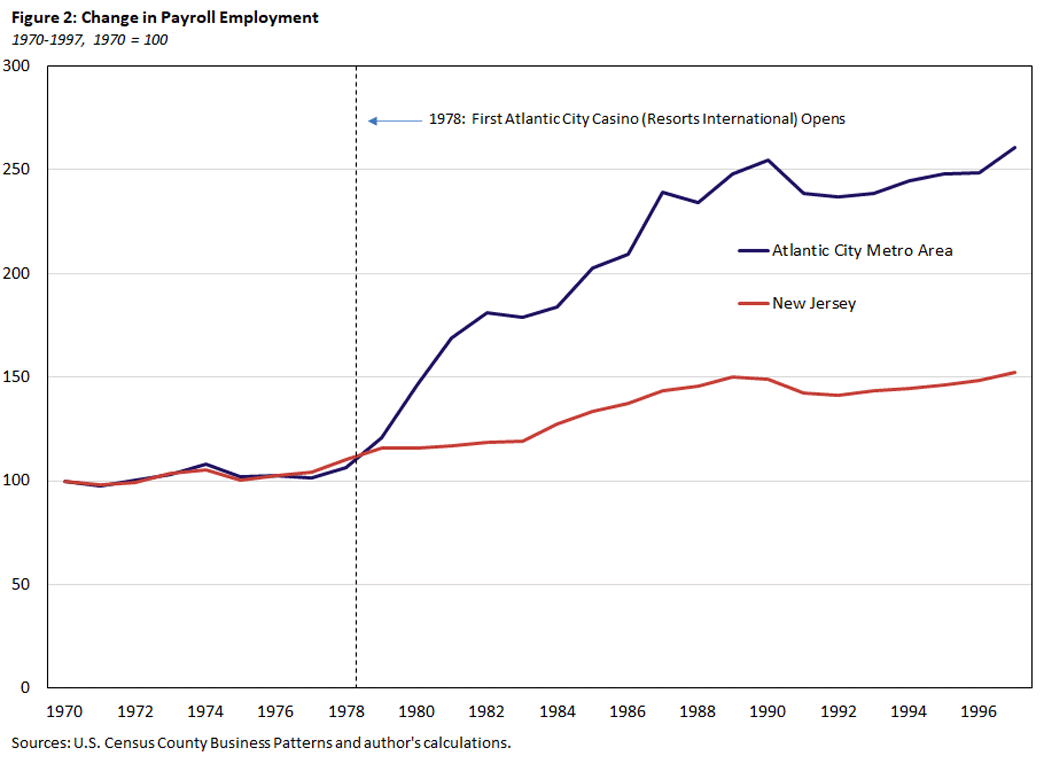

But the 1996 paper "Lessons From the Atlantic City Casino Experience" does suggest that Atlantic City casinos revived Southern New Jersey's "once desperate" regional economy through the 1980s and 1990s by generating capital investment, high-paying jobs and a consistent flow of tourism to the area. Payroll employment in Atlantic City's metropolitan area more than doubled in the 10 years following its first casino (Resorts International) opening in 1978, as seen in Figure 2. Therefore, while the city might not have realized its broader development goals, the region benefited from a steady inflow of jobs.

Moreover, much of South Jersey's early success in generating regional economic development was likely predicated on Atlantic City's regional monopoly on gaming in the Northeast. With nearby states such as Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New York approving and developing commercial casinos over the past 20 years, casinos are less likely to be the regional growth engines that they once were for Southern New Jersey according to recent research.

Atlantic City's experience brings up two questions related to the economic effects of commercial casinos:

- What is the geographic scale of their economic impact?

- How might the existence of other nearby casinos ("market saturation") attenuate it?

The 2008 paper "The Effect of Casinos on Local Labor Markets: A County Level Analysis" studies the labor market effects of commercial casinos and finds positive effects on employment and earnings in surrounding communities. Additionally, the analysis suggests that the employment effect of casino development in a county is inversely related to its population size: Smaller counties tend to benefit more in terms of job growth.

The 2016 paper "Riverboat Casino Gambling Impacts on Employment and Income in Host and Surrounding Counties" studies the introduction of casinos to riverboat states (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi and Missouri) in the 1990s and finds positive impacts on key economic county indicators (per capita income, labor force participation and unemployment rates), with more pronounced impacts in rural areas. The paper finds that the income benefits of casinos are not limited to host counties but also spill over to neighboring ones.

However, this paper also finds that competition between casinos — when casinos open in counties next to other casino counties — diminishes the regional economic benefits. This market saturation effect is further explored by the 2016 paper "An Empirical Framework for Assessing Market Saturation in the U.S. Casino Industry," which suggests that industry growth in saturated regions will depend on either local population growth or income growth. Without such sources of increased demand, the introduction of new casinos will likely come at the expense of nearby existing casinos' revenues.

Vice or Entertainment?

An argument against casino development is that casino gambling is associated with certain ill societal effects, such as problem gambling and impulsive risk-taking behavior.

Problem gambling or compulsive gambling (when individuals gamble to the point where it disrupts their personal and professional lives) is estimated to affect between 0.4 percent to 2.0 percent of the population. Most of the costs of problem gamblers are incurred by several groups:

- The individuals themselves (income lost from work, depression, suicide attempts)

- Their families (divorce, bailout costs)

- Their employers (decreased productivity)

- Their community (strain on public services, theft to pay gambling debt)

The 2009 paper "Are Gamblers More Likely to Commit Crimes?" examines data from a nationally representative survey of young adults and concludes that gambling (particularly the problematic sort) is associated with other risky activities such as binge drinking, hiring prostitutes and using hard drugs. Furthermore, the 2010 paper "The Impact of Casinos in Fatal Alcohol-Related Traffic Accidents in the United States" finds a positive association between the presence of a casino in a county and the number of alcohol-related fatal traffic accidents, with higher rates of accidents in less-populated counties. In other words, impulsive risk-taking behaviors tend to be correlated with one another.

A Criminal Element?

More recent empirical evidence also brings into question the extent to which casinos attract a criminal element to their immediate neighborhoods. On the one hand, commercial casinos from Atlantic City to Las Vegas were notorious mainstays of organized crime for decades, and the prominent 2006 study "Casinos, Crime and Community Costs" suggests that casinos increase county-level property and violent crimes.

On the other hand, when researchers looking at the effects of commercial casinos on local crime rates began to adjust for visitors, the casino effect on crime disappeared, as noted in the 2013 book "Casinonomics." This suggests that casinos draw crime at rates similar to other tourist attractions. In any location, tourists are particularly vulnerable to crime because they are more likely to carry cash, less likely to be familiar with their immediate surroundings and less likely to report crimes to authorities.

Closing Thoughts

Rancorous public debate often blurs the facts on commercial gaming, which has long been a divisive issue in the U.S. To some, gambling is a vice that is detrimental to society and that draws criminal activity. To others, commercial casinos are providers of entertainment (much like sports arenas or amusement parks) that can generate jobs and tax revenues.

Research suggests that casinos are more likely to support economic growth in less dense areas that do not have to compete with nearby casinos, but the evidence of increased tax revenue is limited. While there is a documented empirical link to alcohol-related fatal traffic accidents, there is little evidence that opening a casino will increase crime in a community beyond that of any other tourist attraction.

As casinos and other forms of legalized gambling have proliferated throughout the U.S. over the past 30 years, both the potential upside for the regional economy and the negative community consequences have likely diminished. When gambling was more of a regional monopoly, communities stood to bring in more tourists if they legalized commercial casinos in their state. However, as the means to gamble proliferate and gambling-restricted states dwindle, commercial casino expansion is less likely to induce economic growth.

Adam Scavette is a regional economist at the Baltimore branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. The author would like to thank Thomas Lubik, Sonya Waddell and Doug Walker for their comments that helped improve this article.

In November, Richmond voters rejected a proposal to allow casino development in the city by a margin of under 3 percent. In January, the Richmond City Council voted to pursue a second referendum this coming November. However, the Virginia State Legislature explicitly blocked Richmond from holding a second referendum in 2022 in their budget for Fiscal Year 2023. The state plans to complete a study of an alternative site for casino development in Petersburg before Richmond may proceed with a second referendum in November 2023.

These states included South Dakota (1989), Colorado (1990), Illinois (1990), Mississippi (1990) Louisiana (1991), Indiana (1993) and Missouri (1993).

These states included Maine (2003), Florida (2004), Pennsylvania (2004), Kansas (2007), Maryland (2008), Ohio (2009), Massachusetts (2011) and New York (2013).

These states included Delaware (2012), Nevada (2013) and New Jersey (2013).

States that already allowed sports betting included Oregon, Delaware, Montana and Nevada.

This statistic includes states where single-game sports betting is legally allowed to consumers through retail and/or online sportsbooks.

The New Jersey Casino Revenue Fund Advisory Commission's 2016 annual report noted: "In 1977 legislation was signed into law and the Constitution amended permitting casino gambling in Atlantic City and providing 8% of yearly casino gross receipts to be deposited into the newly created Casino Revenue Fund (CRF) to be used solely for senior and persons with disabilities programs. The CRF was to benefit 'reductions in property taxes, rentals, telephone, gas, electric, and municipal utilities charges for eligible senior citizens and disabled residents of the State.'"

For example, see the 1984 paper "Casino Gambling in Atlantic City: Issues of Development and Redevelopment," the 1996 paper "Lessons From the Atlantic City Experience" or the 2013 book "Casinonomics."

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Scavette, Adam. (July 2022) "Casinos and Regional Economies: Has the Game Changed?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 22-28.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.