The Persistent Decline of LFP Rates for Older Individuals Around the Pandemic

Key Takeaways

- Labor force participation (LFP) rates of all age groups declined dramatically during the pandemic, and even though they have recovered for prime-age (25-54 years old) individuals, they have not recovered for individuals 55 and older.

- Accounting for trends in the LFP rates of older individuals suggests that the pandemic has not affected trends present before the pandemic, and that the prepandemic cyclical peak in 2019 may distort one's interpretation of the behavior of the older individuals' LFP rates.

- Finally, since 2019, the ongoing aging of the population — in particular, the increasing share of those 65 and older with very low LFP rates — has reduced not only the aggregate LFP rate but also the LFP rate of those 55 and older.

Labor force participation (LFP) experienced a bit of a roller coaster ride with the onset of the pandemic. But not all age groups experienced the ride in the same way. For example, we see two very different paths for the LFP rates of prime-age (25-54 years old) individuals on one hand and individuals over 55 years old on the other. In this article, I focus on the latter group, for which (as of September 2024) LFP rates have not recovered to prepandemic levels.

During the early stages of the pandemic, the aggregate LFP rate declined sharply from a cyclical peak of 63.3 percent in February 2020 to 60.1 percent just two months later. Since that decline, the LFP rate has now mostly rebounded to its previous cyclical peak. LFP rates declined for prime-age and older individuals, but while the prime-age LFP rate now exceeds its prepandemic cyclical peak, the LFP rates for those older than 55 have essentially remained at their pandemic levels. It has been argued that early retirement (commonly thought of as retirement before age 65) has played an important role here. Two prominent reasons for early retirement are health concerns exacerbated by the pandemic as well as stock market gains since 2020 resulting in substantial unexpected wealth gains.

In what follows, I will do some simple accounting of the effects of labor market participation decisions by individuals older than 55 on the aggregate LFP rate. This accounting suggests that pandemic changes in LFP rates of these older individuals may not have had persistent effects on the aggregate LFP rate. Rather, it appears that the prepandemic cyclical peak and the early pandemic period may have just obfuscated some long-term trends in LFP rates for those older than 55.1

Accounting for Trends in the LFP Rate

The accounting is based on my work with economist Marianna Kudlyak, where we study the impact of changes in the demographic and educational composition of the population on trends in the LFP rate and unemployment rate.2 We split the population into groups by gender, age and education. We first sort the population into age groups (16-24, 25-34, etc.) and then further divide groups 25 and older into four education groups: less than high school, high school, some college, and college or above. For each group, we calculate the average annual LFP rate from the Current Population Survey micro sample. We can write the aggregate LFP rate as an average of group LFP rates weighted by population share.3

Figure 1 plots the actual aggregate LFP rate and its estimated trend for the period 1976-2023. Like the aggregate LFP rate, we calculate its trend as the population-share weighted average of the trends of group LFP rates.4 The figure shows that the LFP rate is relatively smooth: Deviations from trend tend to be small, certainly compared to unemployment rate movements. Nevertheless, the LFP rate drop during the pandemic and its subsequent fast recovery is quite unusual for the period.

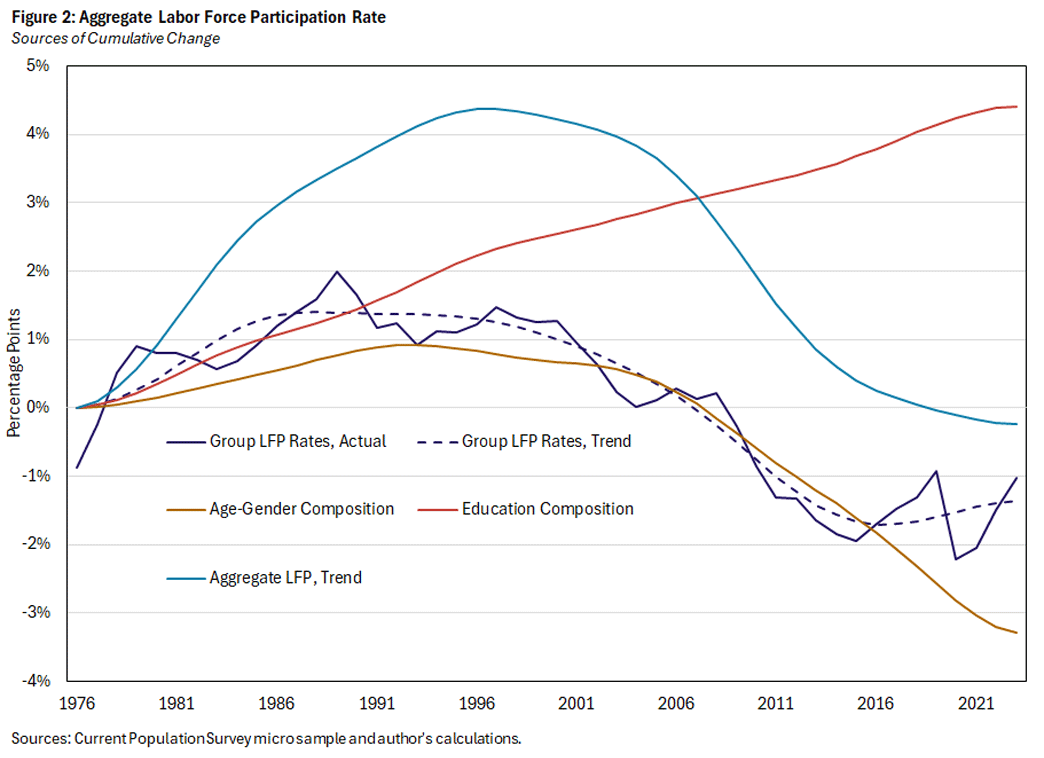

Figure 2 decomposes cumulative changes in the trend of the aggregate LFP rate into three components:

- Changes in the age-gender composition, or the population shares of age-gender groups

- Changes in the education composition, or the education shares of a given age-gender group

- Changes in the trend LFP rates of the different groups

The three components sum up to the trend in the aggregate LFP rate.

The contributions from the demographic factors are quite smooth, and they are important for the overall evolution of the trend in the aggregate LFP rate. Until the early 1990s, all three components contributed to an increase in the aggregate LFP rate: The population was still shifting towards younger and more educated cohorts with higher participation rates, and participation rates of women were increasing. Starting in the early 1990s, participation rates started stagnating for women and declining for men. And in the late 1990s, baby boomers began transitioning to age groups with lower participation rates. Since then, only increasing education has made significant positive contributions to the trend in the aggregate LFP rate.

In fact, even though the trend LFP rates for the demographic groups have positively contributed to the aggregate LFP rate since 2015, the aggregate LFP has continued to decline because of population aging. But changes in actual LFP rates for the different demographic groups before, during and after the pandemic have been unusually large, though also short-lived. The solid purple line in Figure 2 plots the contributions of changes in actual group LFP rates, as opposed to the trends of group LFP rates (the dashed purple line).

The marked cyclical increase before the pandemic stands out, as does the sharp drop in 2020 and subsequent recovery. As mentioned, some of that sharp drop has been attributed to additional early retirement of the older age groups due to health concerns and/or unanticipated wealth increases. But even if these two reasons contributed in 2020-21, it does not appear that they have had a persistent impact on the aggregate LFP rate. We now turn to a more detailed analysis of the LFP rates of the age groups 55 and older.

LFP Rates of Those Older Than 55

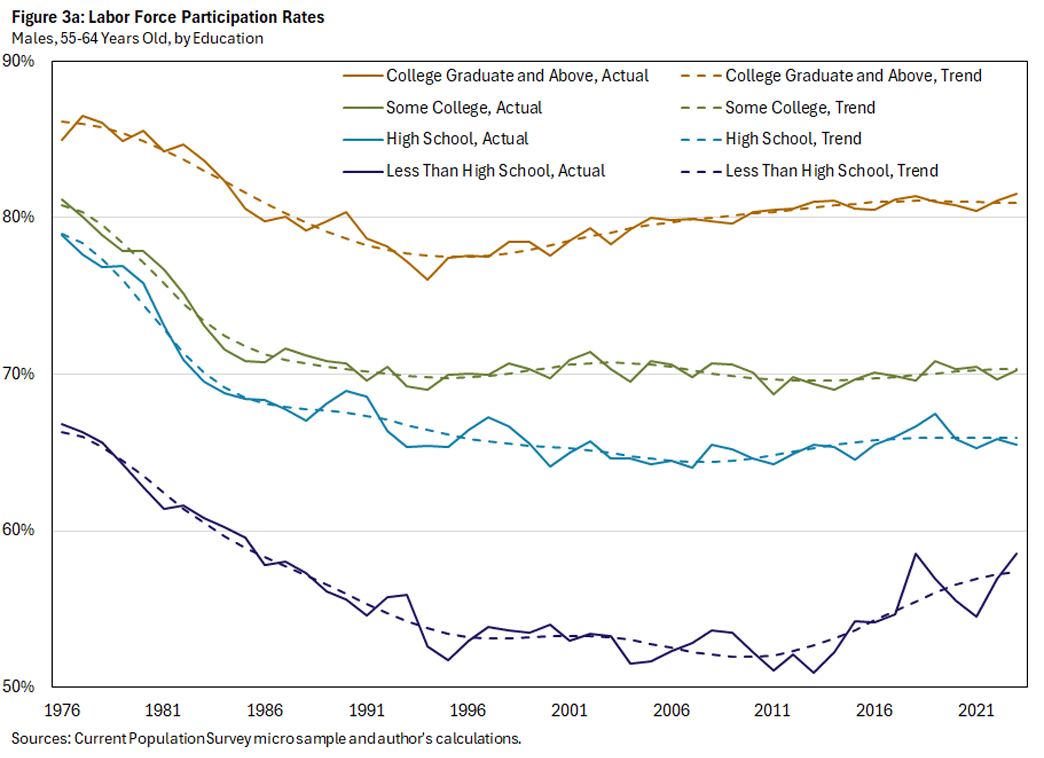

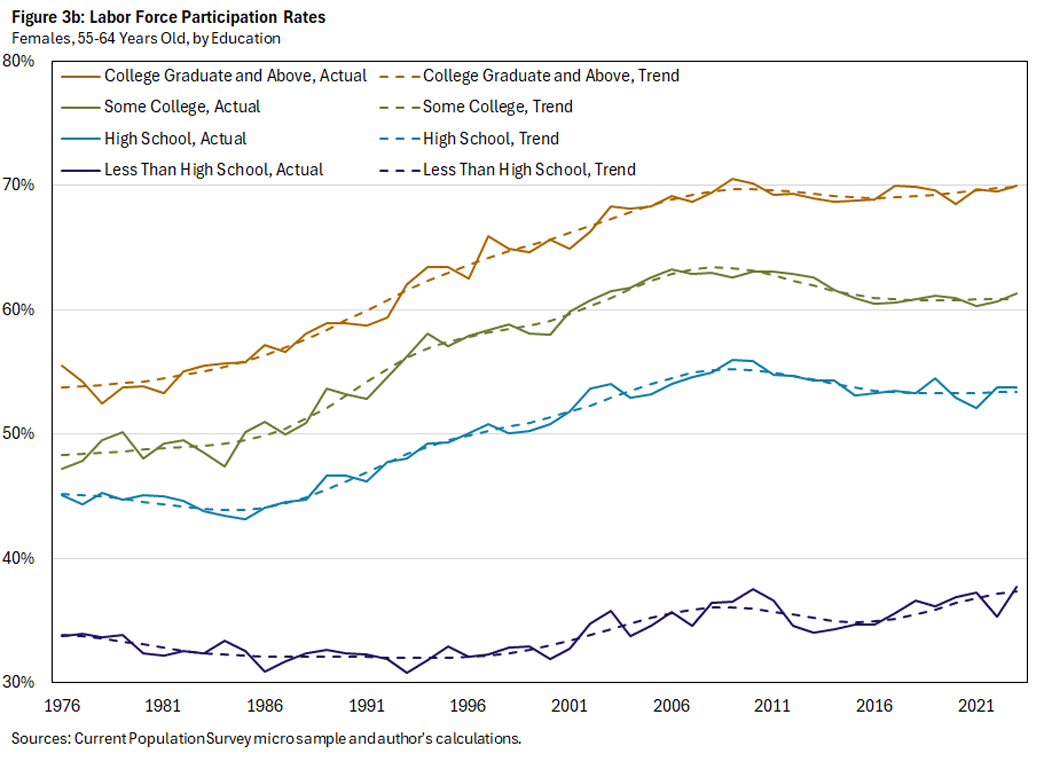

Figures 3a and 3b plot the LFP rates of men and women 55-64 years old by educational attainment. The solid lines represent annual averages, and the dashed lines the corresponding trends.

As we can see, LFP rates are increasing with education: Those with a college degree or higher tend to be about twice as likely to participate than those with less than a high school education.

If we think of early retirement as taking place before age 65, then early retirement does not appear to be a significant factor in declining LFP rates, as there does not appear to be a persistent change in the LFP rates of the age group 55-64. While LFP rates for most education groups drop in 2020, it is difficult to disentangle this decline and subsequent recovery from the 2019 cyclical peak of LFP rates. Consequently, the trend estimates for the groups' LFP rates smooth through the prepandemic and pandemic periods and suggest no change in their trend values with one exception: The group of men and women with less than a high school education displays an increasing trend in LFP rates since at least the mid-2010s.

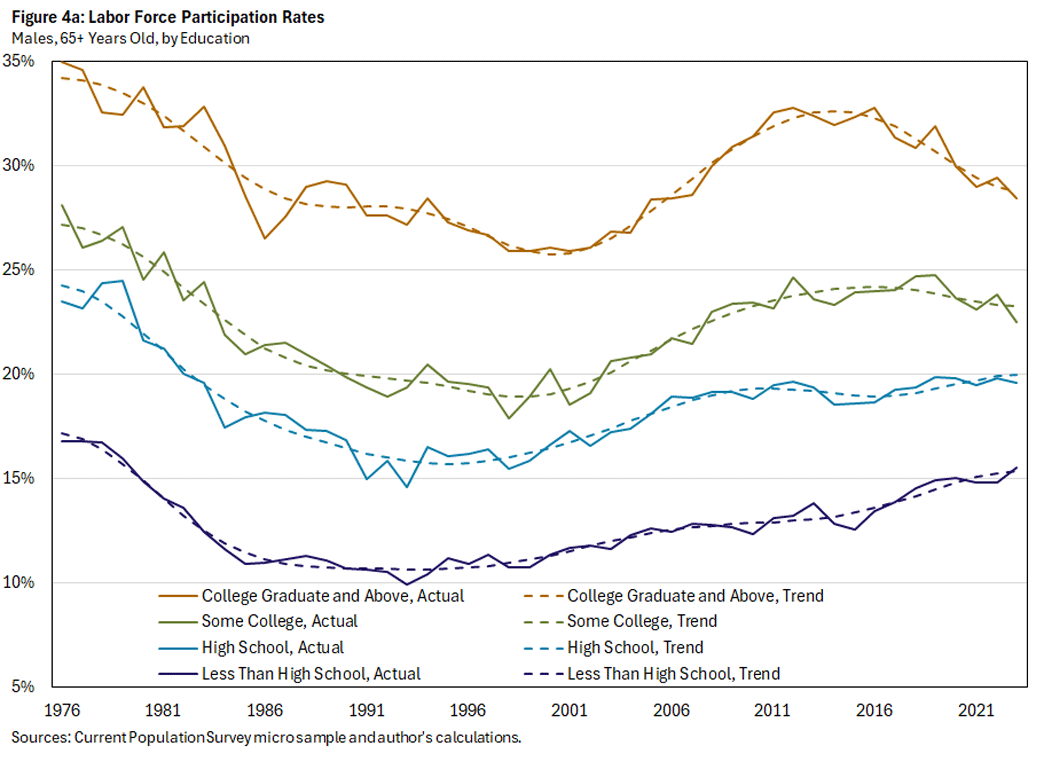

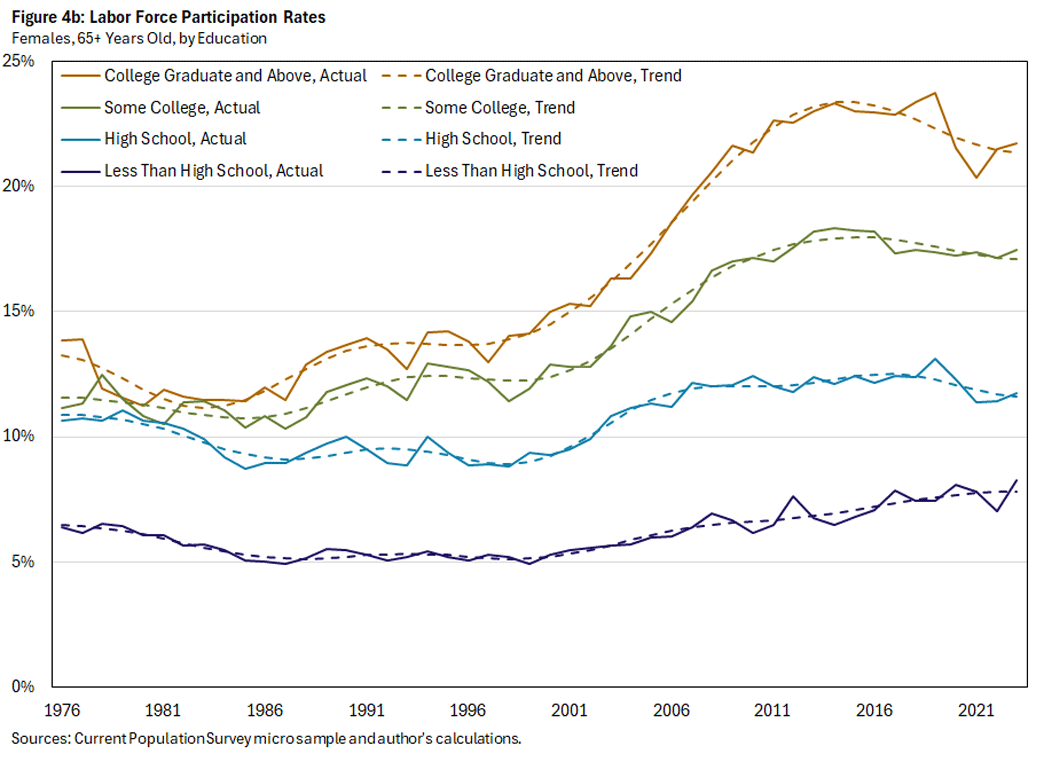

Among those older than 65 years, a persistent decline in LFP rates is apparent for the more educated, as seen in Figures 4a and 4b. It is certainly present for those with a college degree, but after smoothing through the cyclical peak, the 2020-21 drop and subsequent recovery, the decline seems to be a continuation of a trend that started before the pandemic. However, trend LFP rates for those with less than a high school education continue on an upward trend, like those for the ones aged 55-64 years.

To summarize, the trend LFP rates of the 55-64 age group are mostly flat since 2020, whereas the trend LFP rates of those 65 and older mostly continue on their previous downward trend for those with more than a high school education and upward trend for those with a high school education or less.

So, why does the unconditional LFP rate of those 55 and older show a discrete drop in the pandemic with no subsequent recovery? There are two reasons for that. First, when LFP rates attained a prepandemic cyclical peak in 2019, they were above normal. Second, the population is aging rapidly, and the share of those 65 and older among those 55 and older has increased by about 3 percentage points since 2019. Comparing Figures 3 and 4, we see that LFP rates of those 65 and older are about half of those aged 55-64. Thus, the increased relative share of those 65 and older will depress the average LFP rate of those 55 and older.

Conclusion

LFP rates dropped by unusually large amounts around the onset of the pandemic. At the time, this was often attributed to early retirement for older age groups due to health concerns or unexpected wealth gains. Looking at the behavior of these LFP rates during the pandemic period with the benefit of a few more years of data suggests that these drops were either not very persistent or partly reflected long-run trends. Thus, the more interesting questions for policymakers might involve what accounts for these long-run trends in participation rates: Why do they differ across education groups, and why do they seem to change over time?5

Andreas Hornstein is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

I study the behavior of LFP rates for older individuals, and retirement is only one possible reason a person may provide for not participating in the labor market. To the extent that one wants to know if there have been persistent changes in the shares of those available for work, it does not really matter which particular group accounts for these changes. For a paper that specifically focuses on changes in retirement among the older age groups during the pandemic, see the 2022 paper "The Great Retirement Boom" by Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith and Juliana Dajon. And the 2024 paper "Pandemic Labor Force Participation and Net Worth Fluctuations" by Miguel Faria e Castro and Samuel Jordan-Wood discusses how changes in net worth might have affected retirement decisions.

See, for example, our 2022 article "The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends."

We only consider annual data up to 2023, but this should not be too much of a limitation since the LFP rate has been relatively stable in 2024.

Unlike in our 2022 article, I calculate group trends using the methods in the 2008 paper "Testing Models of Low-Frequency Variability" by Ulrich Müller and Mark Watson. This method is frequency-based, and each group's trend is restricted to movements with a periodicity of more than 12 years.

The 2022 paper "Shocks, Institutions and Secular Changes in Employment of Older Individuals" by Richard Rogerson and Johanna Wallenius investigates some of the issues involved.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Hornstein, Andreas. (November 2024) "The Persistent Decline of LFP Rates for Older Individuals Around the Pandemic." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 24-34.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.