How Is Housing Handled in the National Income and Product Accounts?

Key Takeaways

- The housing sector largely contributes to the volatility of GDP and is behind recent inflation dynamics.

- We offer some insights on how housing is handled in the National Income and Product Accounts.

The National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) are prepared by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) to provide a comprehensive picture of the nation's economic performance. Measuring the multitude of economic transactions for a variety of spending categories, sectors and regions is a formidable task that often involves imputing missing data and choosing how to analyze specific statistics. In this article, we focus on how NIPA measures economic activity in a particular sector: the housing sector, as it is highly sensitive to business cycle variations and changes in monetary policy. In addition, as we discuss below, a significant part of the recent inflation surge is associated with inflation in the housing market. It is therefore instructive to understand how housing services are recorded in the NIPA and how they impact the overall measures of production, income and prices.

Measuring Domestic Output: GDP and GDI

Before discussing how housing shows up in the NIPA, we briefly explain how the BEA measures the overall output in the economy. Gross domestic product (GDP) is measured by summing all the spending on domestic goods and services, which is called the expenditures approach. Private consumer spending, firms' investment purchases, government spending and spending by other countries on U.S. goods and services (minus spending by U.S. consumers on goods and services of other countries) are all examples of expenditures that are part of GDP.

An equivalent way to measure production is to add up all the payments received by factors of production as well as the government. This is called the income approach to measuring production, or gross domestic income (GDI). GDI consists of labor income, firm profits, rental income (from housing or financial assets) and taxes. Since a dollar spent is a payment for a factor of production, GDP and GDI should in theory be equal.

GDP is "gross" because investment is recorded as a gross amount. That is, it includes spending not only on new investment but also toward maintenance and replacement of capital (called consumption of fixed capital or depreciation). To make GDP and GDI consistent, NIPA adds the consumption of fixed capital to the income approach.

How does the housing sector show up in the NIPA? We explain the contribution of housing into measurement of GDP and GDI, respectively.

Housing in GDP

When a new house is built, the economic resources spent for its construction are recorded in GDP under the category of residential investment. This category includes the value of new construction and improvements or additions to existing housing units, as well as costs associated with selling houses (the movements of which can significantly impact residential investment). Purchases of equipment built into the house (such as a heating unit) also fall under the category of residential investment.1

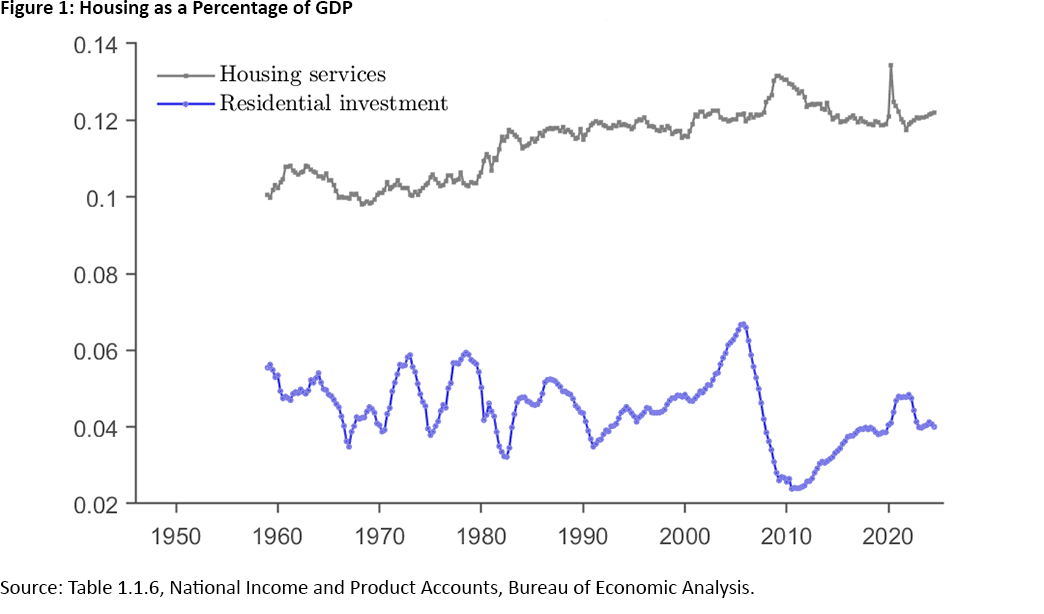

Figure 1 plots residential investment over time as a percent of GDP. Residential investment was about $1.1 trillion in the second quarter of 2024, is approximately 4 percent of GDP and is one of the most volatile components of GDP.

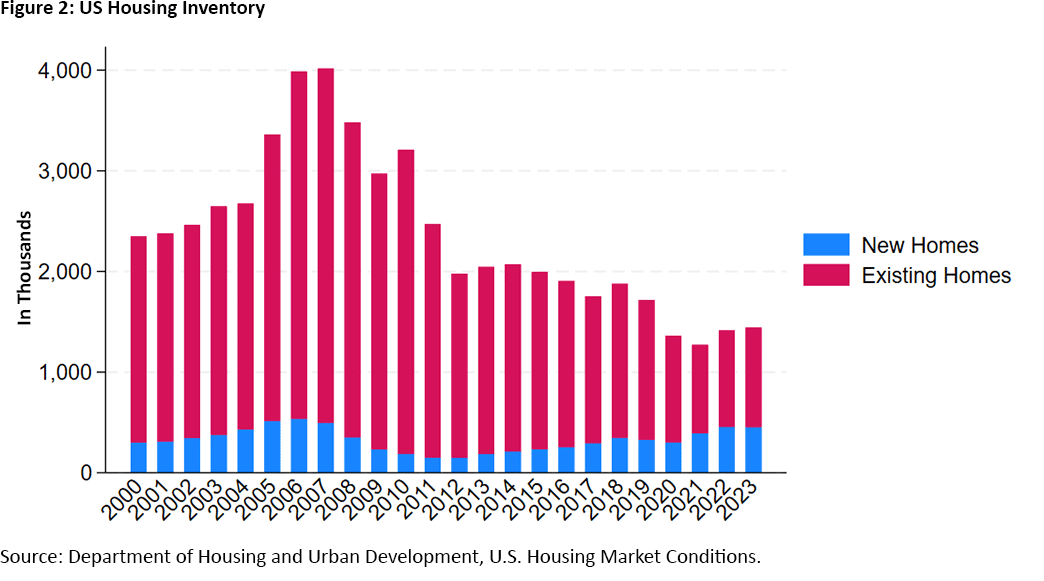

Figure 2 shows the number of houses available for sale over time, with around 1.4 million homes up for sale in 2023. Over the last 10 years, the number of existing homes on sale has declined, but construction of new homes has increased.

Housing affects GDP not only through investment but also through consumption. An example would be a machine in a factory. When the machine is produced, the spending of economic resources is recorded under investment spending. But the machine itself also produces some goods or services, which are counted for GDP as well. That is, there is production of the capital good itself, and there is also production arising from the newly produced capital good.

In a similar fashion, construction of a house uses economic resources, and the house also produces an important service (providing shelter to its tenant). When a household rents a house, the rents constitute spending recorded under private consumption expenditures (in particular, services) in GDP.

But how should we classify spending if the owner of the house stays in the house? The NIPA treats home ownership as if the owner-occupants rent the homes to themselves. The "spending" associated with the services from owner-occupied housing is computed based on similar tenant-occupied housing. Even when houses are temporarily vacant, they technically still provide services to the owner. This way, what matters for consumption expenditures is the number of houses and the rental value of units, not the division of households between homeowners and renters. Figure 1 also plots the housing service component of GDP, which was around 12 percent of GDP in the second quarter of 2022.

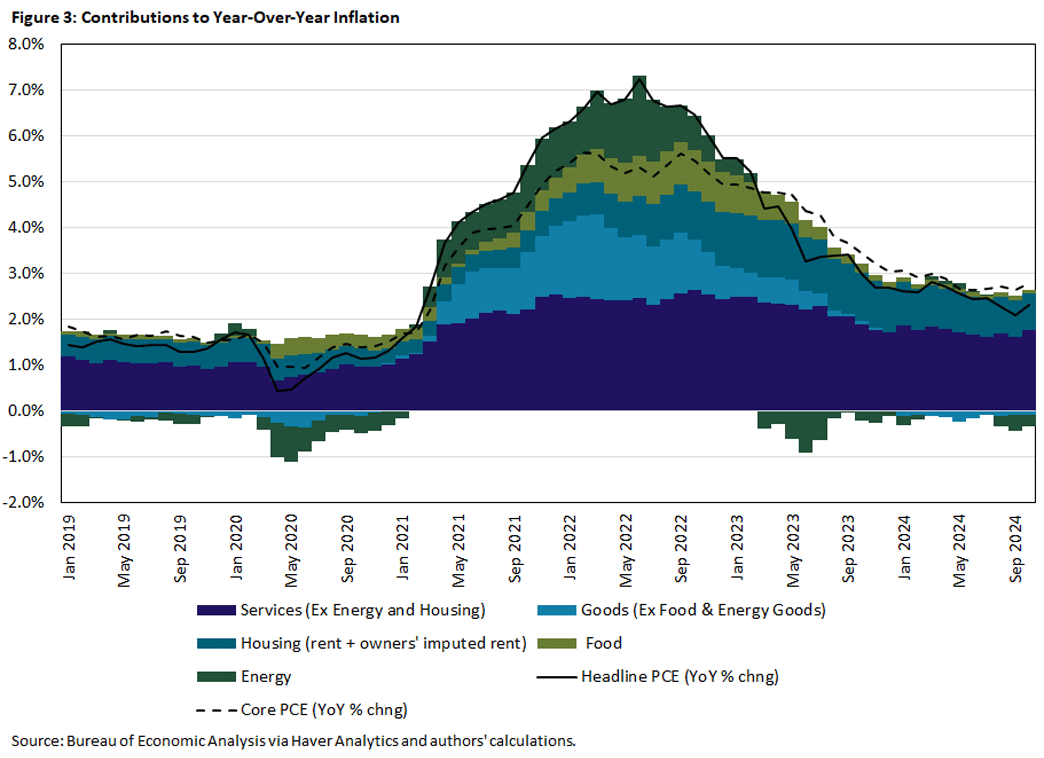

Housing services — particularly the "imputed rents" of homeowners — play a key role in inflation. Because rents are slow to change — as they generally remain fixed over the life of a lease (typically one year) — this component of inflation can introduce significant persistence in overall inflation readings. As shown in Figure 3, a significant part of the COVID-related inflation surge is associated with housing inflation: The housing component remains elevated through the present, despite a normalization in other inflation categories such as core goods, energy and food.

Housing in GDI

Earnings from house rentals are also part of GDI. Rental income was around 3.5 percent of GDI for the second quarter of 2024, and these rents include both rents that tenants pay to landlords and the imputed rental income of owner-occupants.

The NIPA treats a housing unit similarly to a business. Just like a business owner subtracts production expenses when measuring business income, the homeowner measures rental income net of depreciation and costs associated with maintaining the property. Examples of such expenses include maintenance, property taxes and mortgage interest. Once they are deducted from the rent, what remains is a "profit-like remainder" of rental income.

Subtraction of these expenses from rental income does not imply subtraction from national income itself. For example, property taxes are recorded as income of local governments. Meanwhile, the interest portion of mortgage payments contributes to the revenue and profits of the financial intermediates that issue mortgages. Profits made by these companies are generally counted in the corporate profits' component of GDI.

Conclusion

In this article, we described how economic activity in the housing sector is recorded in the National Income and Product Accounts. Houses are investment goods and also provide consumption services. Understanding how these components are measured offers insights into recent inflation dynamics.

Marios Karabarbounis is a senior economist and John O'Trakoun is a senior policy economist, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Karabarbounis, Marios; and O'Trakoun, John. (January 2025) How Is Housing Handled in the National Income and Product Accounts? Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-04.

Note that, beyond residential investment, there is also production of buildings and structures for firms (such as factories and offices). In this article, we focus only on residential investment for simplicity, but the same lessons can apply to these other structures.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.