The Debt Brake: Unsafe at Any Speed?

Key Takeaways

- The German debt brake is designed to prevent excessive accumulation of government debt. It is not just a simple fiscal policy rule but enshrined in the country's constitution to prevent political meddling.

- While it has served its stated purpose, it is also often blamed for Germany's lackluster economic performance in the form of low productivity and low GDP growth when compared to the other countries of the eurozone and especially the U.S.

- Theoretical research shows that fiscal rules like the debt brake can potentially destabilize economies or lead to real and nominal indeterminacy.

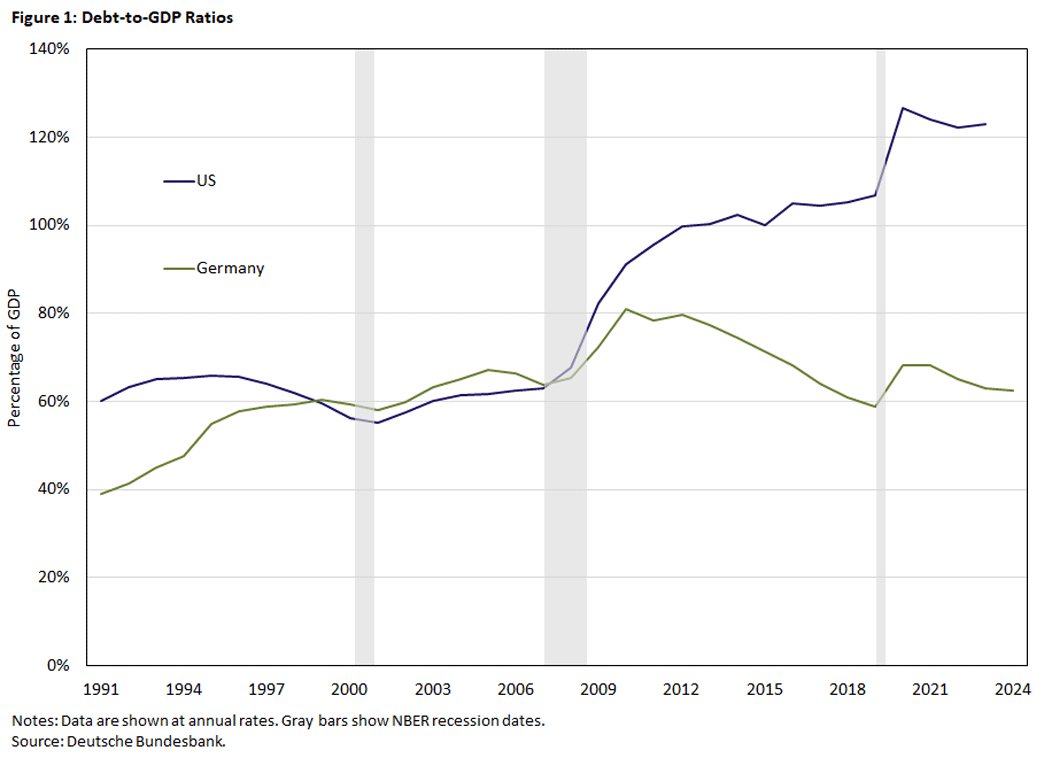

Over the last two decades, most advanced economies have seen a sharp rise in the level of government indebtedness: Debt-to-GDP ratios have reached levels above 100 percent, which many economists previously considered unsustainable. Broadly speaking, the two proximate factors for this rise are the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007-09 (and the connected European debt crisis in 2011-13) and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020.

However, one advanced economy that didn't experience such an increase is Germany. Figure 1 shows the growth of the government debt burden in Germany and the U.S. since the early 2000s. In both countries, the debt-to-GDP ratio was around 60 percent but rose sharply during and after the GFC. But while U.S. debt continued growing (albeit at a declining rate), the German debt ratio fell throughout the 2010s after its peak of 80 percent in 2011. Similarly, the pandemic led to another spike in U.S. indebtedness, reaching almost 130 percent in 2021. In Germany, a small increase during the pandemic was followed by a declining debt ratio back towards 60 percent.

In 2009, in the wake of the GFC, Germany introduced a bold constitutional reform designed to enforce long-term fiscal discipline: the debt brake (or Schuldenbremse in German), which was enshrined in the German constitution (the Grundgesetz or Basic Law). The debt brake is effectively a fiscal rule that limits structural deficits at both the federal and state levels, placing a ceiling on how much debt the government can accumulate outside of times of crisis. The goal was to insulate fiscal policy from short-term political pressures and safeguard public finances from the risk of unsustainable debt.

For more than 15 years, the debt brake has been a central pillar of Germany's economic governance, arguably succeeding in limiting (and even reducing) the size of the debt burden. However, it became a flashpoint in debates about Germany's broader economic trajectory. Supporters argue it has delivered on its core promise. But critics contend that this success has come with several costs:

- A sluggish economy

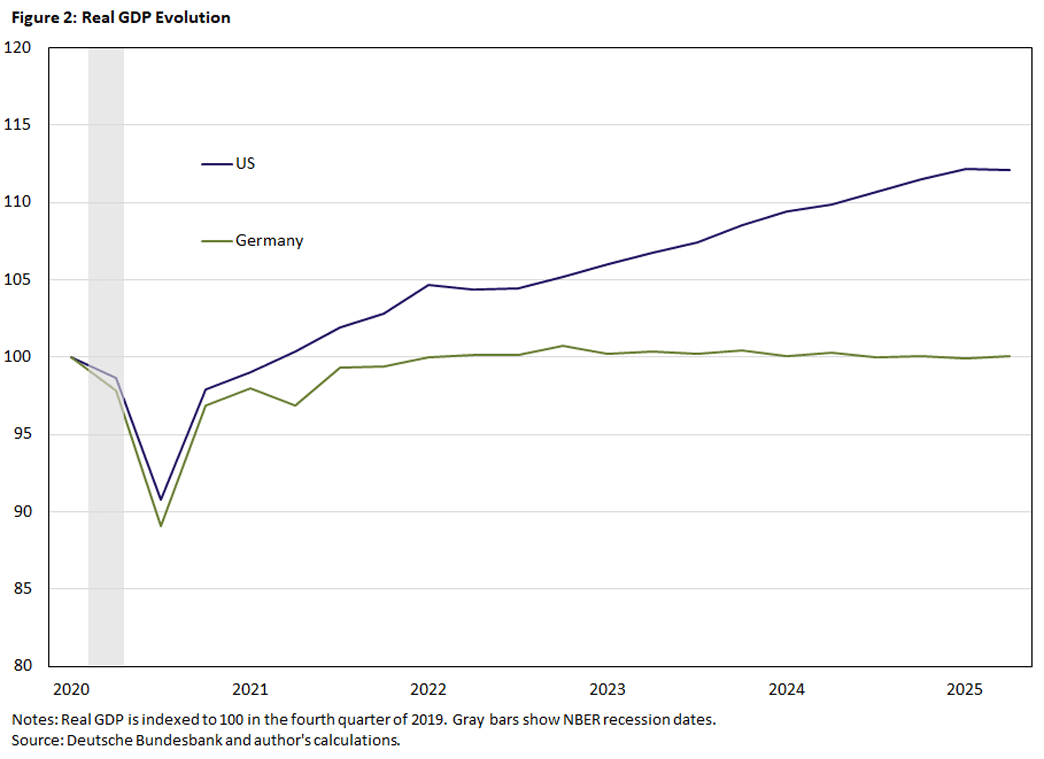

- Nonexistent GDP growth during the recovery from the pandemic (as seen in Figure 2)

- A lack of investment in infrastructure

- Inability to meet increasing demands for climate1 and military spending

- A general sense of malaise

In this article, I discuss the pros and cons of the debt brake against the background of Germany's economic performance over the past decade. I connect this debate with an academic literature from 30 years ago on the perils of balanced-budget rules. In doing so, this article asks whether the debt brake remains fit for purpose or whether (in today's context) it is unsafe at any speed.2

A Rule Born of Crisis: The Origins of the Debt Brake

The Schuldenbremse was introduced in 2009 against the backdrop of the GFC and the emerging eurozone sovereign debt crisis. Concerned about rising public debt levels and the erosion of market confidence in fiscal sustainability across Europe, German policymakers sought to embed fiscal discipline into the constitutional framework of the state. The result was a reform of Article 109 and Article 115 of the Basic Law, which imposed strict limits on structural deficits: no more than 0.35 percent of GDP at the federal level and a near-complete prohibition on borrowing at the state level.

In a sense, the debt brake was a child of its time, as it reflected a broader shift in European economic governance characterized by a strong emphasis on fiscal consolidation. But in Germany, the debt brake was more than a policy tool: It was a political statement. Designed to limit discretionary fiscal expansion and shield budgetary decisions from electoral pressures, it institutionalized a long-standing cultural preference for budgetary prudence.

In practice, the rule has been both binding and symbolic. While escape clauses allow for temporary suspension in times of emergency — a provision used during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example — the political commitment to the debt brake has remained strong. However, this consensus has started to fray over the last five years.

One key factor is certainly the poor performance of the German economy during this time. Figure 2 compares the pandemic recoveries of the U.S. and Germany. While GDP in both countries experienced similar initial declines, U.S. GDP picked up quickly, and it now stands 12 percent above its level in the fourth quarter of 2019, consistent with trend U.S. productivity growth over the last decades. On the other hand, Germany's GDP is at the same level as it was in 2019.

In late 2023, the German Constitutional Court ruled against the government's attempt to reallocate unused pandemic funds to the Climate and Transformation Fund as a violation of the debt brake, throwing a spotlight on the rigidity of the framework. In response, the German parliament passed a relaxation of the rule in March 2025 and reopened a national conversation about whether the debt brake may be inhibiting much-needed public investment.

The Popular Case for the Debt Brake

The economic rationale for the debt brake rests on the principle of intertemporal budget discipline, or designing fiscal policy in such a way to maintain the sustainability of a country's debt.3 According to the intertemporal government budget constraint, the present value of future primary surpluses must equal the existing stock of public debt for solvency to be maintained. If left unchecked, persistent primary deficits can push debt onto an unsustainable trajectory, increasing the risk of default. By capping primary deficits, the debt brake aims to enforce this intertemporal constraint through legal fiat.4

Such a rule-based framework enhances the credibility of fiscal policy, as a constitutional constraint serves as a commitment device that reduces the temptation to finance politically expedient spending through debt. History abounds with episodes where excessive spending ultimately led to sovereign defaults and hyperinflations. In the German context, the hyperinflation of 1923 scarred the German psyche to such an extent that excessive public and even private borrowing is seen as a moral fault and provides widespread support for the debt brake.5

But even short of such extreme outcomes, the debt brake is also designed to prevent electoral spending cycles or political business cycles. In this light, the debt brake functions not only as a constraint on fiscal policy but as a cornerstone of macroeconomic stability, particularly in a monetary union where individual member states lack monetary sovereignty.

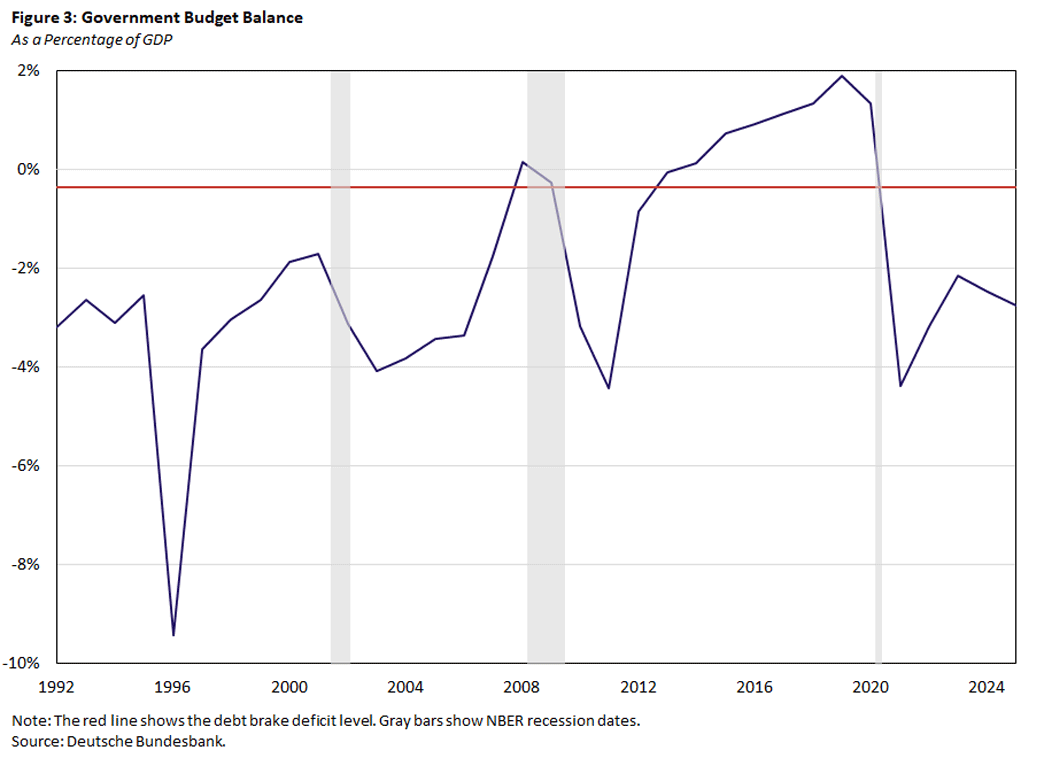

Empirically, proponents point to Germany's post crisis fiscal performance as validation. The debt brake has coincided with a steady decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio from its peak in the early 2010s, arguably helping Germany regain its role as a fiscal anchor within the eurozone. Figure 3 shows the German deficit-to-GDP ratio since reunification. The decline in government debt visible in Figure 1 coincides with the sharp rise in surpluses after the GFC when the debt brake was fully in effect. However, and notably, budget surpluses were considerably above the constitutionally imposed limits.

The Popular Case Against the Debt Brake

While the debt brake has contributed to fiscal consolidation, opponents argue that it has imposed significant economic costs, particularly in the form of underinvestment and structural stagnation. The constraint on borrowing (even for productive purposes) limits the government's ability to respond to long-term challenges such as aging infrastructure, digitalization and energy transition. This has led to concerns that Germany's fiscal orthodoxy, while well-intentioned, is ill-suited to the demands of an economy needing structural change, especially in a low-interest, high-investment global environment.

Conceptually, government borrowing is not inherently problematic. When public investment yields a return higher than the cost of financing, it can enhance long-run productivity and growth. Standard models of optimal fiscal policy suggest that governments should smooth consumption and investment over time, borrowing during downturns or periods of structural change. By tying the hands of fiscal policy even in favorable borrowing conditions, the debt brake generally inhibits this process and biases spending away from investment toward politically easier-to-cut expenditures.

Moreover, the last quarter century has been described as a period of secular stagnation, characterized by sluggish output and productivity growth, low and falling interest rates, and subdued inflation.6 In the presence of secular stagnation, the opportunity cost of public borrowing is arguably lower than in previous decades. That is, public investment financed by borrowing is effectively cheap in the sense that the social rate of return is higher than the rate at which the government can borrow. Under these conditions, failing to invest may be more harmful to intergenerational equity than modest debt accumulation.

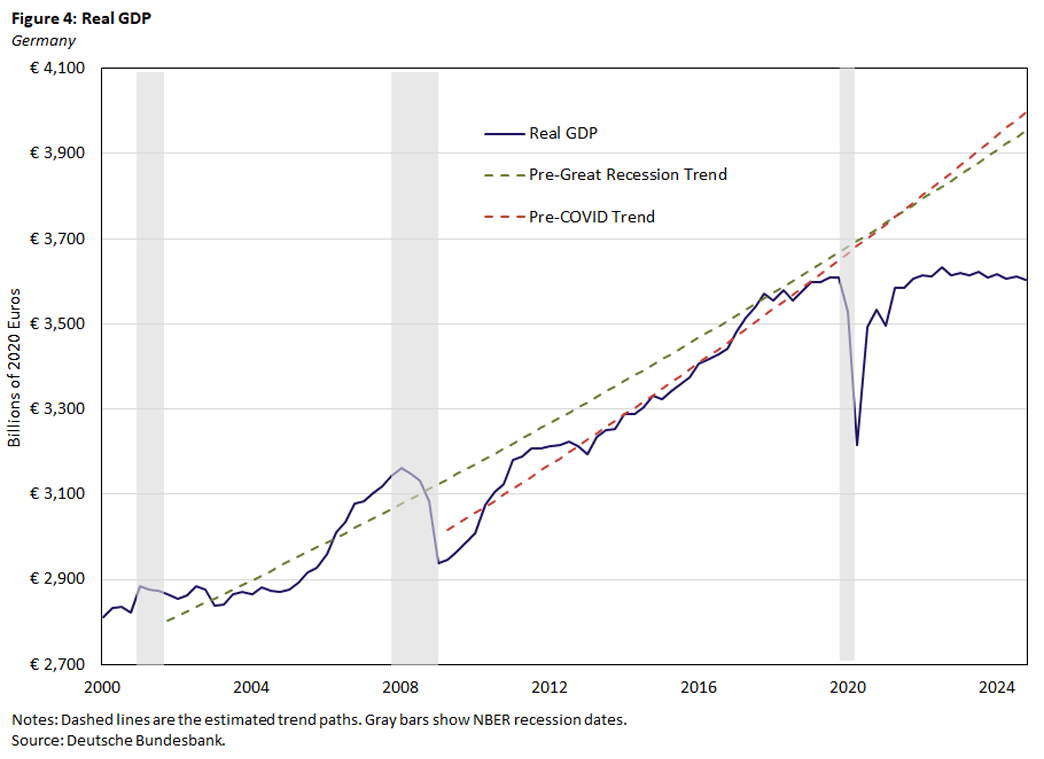

Figure 4 shows the level of German GDP since 2000. The dashed lines are the estimated trend paths for the beginning of the sample in 2000 until the fourth quarter of 2019 and for the period beginning at the end of the GFC through the fourth quarter of 2019, with growth rates of 1.49 percent and 1.82 percent, respectively. The figure suggests that the debt brake did not hinder GDP growth in the 2010s. If anything, growth was slightly higher than the longer trend. In fact, the decline in the deficit and the fall in the debt burden (seen in Figures 1 and 3) could have been precipitated by the strong economy and consequent tax collections.

At the same time, studies suggest that Germany's chronic public underinvestment has contributed to weak productivity growth and declining potential output. These trends predate the COVID-19 shock but have been exacerbated in its aftermath.7 As Figure 4 shows, growth after the pandemic has been nonexistent (which can also be seen in Figure 2), with current GDP at the same level as right before the pandemic. Had the German economy reverted to its prepandemic growth path, per capita GDP would have been €12,500 higher.

There are certainly plenty of other potential explanations for this anemic performance: Russia's attack on Ukraine (which disrupted the flow of cheap energy to the main German manufacturing sectors), China's emergence as a manufacturing powerhouse (which led to the waning of Germany's export-led model of growth), and the costs and distortions associated with the German government's avowed goal of an energy transition away from carbon-based sources to renewables. Yet, the debt brake presents a situation where the government is perhaps handicapping itself.

It has also been argued that the debt brake may be politically distortionary. By ruling out debt financing, policymakers may resort to off-balance-sheet mechanisms, creative accounting or underfunding essential services to comply with the letter of the law. This can obscure the country's true fiscal stance and shift costs into the future, precisely the outcome the debt brake was designed to avoid.

Balanced-Budget Rules as Sources of Macroeconomic Instability

The inflexibility of the debt brake figures prominently in the context of macroeconomic stabilization policies. Unlike discretionary fiscal policy (which can respond dynamically to shocks), a rigid rule-based approach can dampen the government's countercyclical capacity. Even though the debt brake has emergency clauses, the procedural and legal thresholds for activating them create uncertainty and delay. This rigidity may undermine fiscal policy's role as an automatic stabilizer, especially when monetary policy is constrained by the effective lower bound. But academic research has identified additional concerns.

In two seminal papers from the 1990s, economists Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé and Martin Uribe explore how fixed deficit rules (such as the German debt brake) lead to macroeconomic instability, the opposite of what is often considered one of the advantages of such rules.

In their 1997 paper "Balanced-Budget Rules, Distortionary Taxes and Aggregate Instability," they study the macroeconomic implications of balanced-budget rules in the context of a neoclassical growth model with distortionary taxation on labor income. Their central finding is that balanced-budget rules can give rise to aggregate instability. Specifically, such rules can generate expectation-driven fluctuations: When future tax increases are expected, they reduce current labor supply and output and, thus, tax revenue. In turn, these expected increases validate (through the budget constraint) the need for higher taxes, making the expectations self-fulfilling.

The mechanism operates through the interaction between labor income taxation and the government's need to finance spending without running deficits. Because taxes distort labor supply decisions, any anticipated increase in future tax rates lowers current labor supply and output, shrinking the tax base. This negative feedback loop can create multiple rational expectations equilibria (including unstable ones), even when the balanced-budget rule is perfectly adhered to.

At the heart of this mechanism is the inescapable power of the intertemporal government budget constraint. It stipulates that outstanding debt must be backed by future surpluses. While this puts a constraint on how much debt an economy can carry without default or policy changes (the so-called "fiscal space"), a deficit rule throws a spanner in the works. Anticipation of future downturns reducing tax collection or higher expenditure to finance military conflicts triggers anticipation of higher rates precisely because government debt cannot be used as a shock absorber.

In their follow-up 2000 paper "Price Level Determinacy and Monetary Policy Under a Balanced-Budget Requirement," Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe extend this argument to a monetary economy under various monetary policy rules. In the absence of the distortionary taxation mechanism, a balanced-budget rule remains treacherous, depending on the interplay of the fiscal rule with the specific monetary regime.

Under a nominal interest rate peg — that is, when the central bank maintains a fixed nominal interest rate — Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe find that the price level becomes indeterminate. This indeterminacy arises because the fixed interest rate combined with the balanced-budget rule restricts the government's ability to adjust fiscal variables in response to economic shocks, leading to multiple potential price levels consistent with equilibrium.

In contrast, under a regime where the central bank targets a constant growth rate of the money supply, the model implies that the price level is determinate. In this scenario, money supply growth provides a nominal anchor, even in the presence of a fixed deficit rule.

Finally, when considering typical interest-rate feedback rules, price-level determinacy hinges on the responsiveness of the interest rate to inflation. Specifically, the price level is determinate when the interest rate responds moderately to inflation but becomes indeterminate when the responsiveness is either too weak or excessively strong.

Both papers challenge the conventional view that fiscal rules promote stability and discipline. They show that balanced-budget requirements can in fact destabilize the economy. The key takeaway is that fiscal rules must be carefully designed in conjunction with both the structure of taxation and the stance of monetary policy. Germany's constitutional debt brake does not require a zero deficit, but it operates under similar constraints and carries some of the same risks. This is especially true if political or legal rigidity undermines the flexibility needed during downturns or structural transitions.

International Comparisons

Germany's debt brake is among the most stringent fiscal rules in advanced economies, especially given its constitutional status and limited room for discretion. While many countries have adopted fiscal rules — typically targeting deficit or debt ratios as in the case of the Maastricht Treaty that preceded the European Monetary Union — few have embedded them so deeply into legal frameworks.

The U.S., for instance, has long debated the merits of a federal balanced-budget amendment, but efforts to enshrine such a rule in the Constitution have repeatedly failed due to concerns about fiscal flexibility and macroeconomic management. Some U.S. states, however, operate under their own balanced-budget requirements, though enforcement mechanisms and definitions vary widely.

Within the European Union, the Stability and Growth Pact sets fiscal limits at the supranational level, but enforcement has proven inconsistent, and reform discussions are ongoing. In contrast, Germany's debt brake remains distinctive in its combination of legal rigidity, federal-state reach and political salience.

Summary and Conclusion

Once lauded as a model of fiscal discipline, Germany's debt brake now stands at the center of a growing debate over its broader economic consequences. A rich body of both theoretical and empirical research — including by Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe — suggests that strict balanced-budget constraints can produce significant macroeconomic costs, including real and nominal instability. In addition, a key concern has been that the debt brake inhibits vital public investment by disallowing deficit-financed spending, even when borrowing costs are low and infrastructure needs are high. This constraint has become especially pressing considering Germany's commitments to green transformation and defense modernization. The experience with the German debt brake thus presents a cautionary tale if the discussion about a balanced-budget amendment in the U.S. ever resurfaces.

Thomas A. Lubik is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Discussions of Germany's debt brake and its impact on government spending specifically cite the impact on Klima (or climate) and Klimawandel (or climate change), so we'll be referring to climate in this article.

In response to the rising concerns about Germany's current economic situation, the debt brake was amended in March 2025 to allow for specific exemptions. The German parliament approved changes that permit defense spending exceeding 1 percent of GDP to be exempt from the debt brake's borrowing limits. Additionally, a €500 billion infrastructure fund was established, with €100 billion earmarked for climate-related investments. While the debt brake's fundamental framework persists, these targeted modifications allow for increased borrowing in designated areas.

This idea is discussed in further detail in my 2020 article "Public and Private Debt after the Pandemic and Policy Normalization" (co-authored with Felipe Schwartzman) in the context of the run-up in debt during the pandemic. I expand on this topic in my 2022 article "Analyzing Fiscal Policy Matters More Than Ever: The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level and Inflation."

The debt brake allows for a small deficit. If the economy grows at a rate that is higher than the real rate of interest on its debt, then even deficits can be sustainable. The economy simply grows out of its indebtedness. This is slightly different from a balanced-budget rule.

The fiscal demands for reparations in the Versailles Treaty and the dire state of the German economy after World War I led the Reichsbank (the German central bank at that time) to print money to finance the deficit. It eventually (but then very quickly) led to hyperinflation. This and other hyperinflations are discussed in the 1982 chapter "The Ends of Four Big Inflations (PDF)" by Thomas Sargent in Inflations: Causes and Effects.

See the 2016 article "The Age of Secular Stagnation" by Lawrence Summers.

This debate is comprehensively discussed and summarized in the 2021 paper "The German Debt Brake: Success Factors and Challenges" by Lars P. Feld and Wolf H. Reuter.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Lubik, Thomas A. (June 2025) "The Debt Brake: Unsafe at Any Speed?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-22.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.