How Private Information Distorts OTC Market Outcomes

Key Takeaways

- Information frictions in over-the-counter markets reduce asset creation, trading volume and overall welfare compared to complete information economies.

- Because investors can't easily gauge others' private valuations of assets, potentially efficient trades are lost.

- Private information skews ownership and trading patterns, favoring high-valuation investors and reducing the role of middlemen.

In traditional exchanges — which include stock markets like the New York Stock Exchange — trading and communication about prices are centralized and subject to formal rules. Whenever a trade happens, the price is communicated to all market participants.

Unlike in a traditional exchange, trades in an over-the-counter (OTC) market aren't matched through centralized order books. Instead, buyers and sellers negotiate terms bilaterally (that is, investor to investor) with limited knowledge about, for instance, other quotes and executions in the market. Thus, OTC markets are said to be relatively opaque. Does this uncertainty and decentralized structure distort market outcomes, such as asset supply, trade volume and yields? One area where the effects of this question might be felt is public finance, as municipal bonds, for instance, are frequently traded in OTC markets.

I (Nicholas) study this trading environment in my working paper "Private Information in Over-The-Counter Markets," co-authored with Zachary Bethune and Bruno Sultanum. We build a quantitative model in which assets are first issued in a primary market and later traded in a secondary OTC market, and we calibrate this model with data from the U.S. municipal bond market. Our findings highlight several negative effects of information frictions, including various inefficient market outcomes and an inefficient distribution of investors.

Model Setup

Two types of agents operate in the model:

- Issuers, who create new assets but don't want to keep them

- Investors, who can buy and hold assets

An investor is either an owner (holding one asset) or a nonowner (holding none). All assets pay a known and fixed dividend, but each investor values holding an asset differently. This personal valuation is called their "type" and is private information.

There are two markets where assets can change hands. In the primary market, issuers sell newly created assets directly to nonowner investors. In the secondary OTC market, existing assets are traded between investors. Issuers in the primary market receive random opportunities to create assets. When one arises, the issuer draws a random cost of issuance and decides whether the potential profit justifies producing the asset. Meanwhile, in the secondary market, investors are matched at random with other investors and can trade if the terms are favorable.

Intuition for Trading Under Information Frictions

What can this model tell us about the impact of private information on market outcomes? Under complete information, trade happens efficiently: In the primary market, issuers sell assets to nonowner investors whenever the investor's valuation exceeds the cost of issuance. And in the secondary market, an investor sells an asset if the buyer values it more. This ensures assets are held by those who value them most.

But under private information, each investor's valuation is unknown to others and costly to learn. Sellers have difficulty appraising buyers' true valuations, which allows buyers to extract "informational rent," or extra surplus gained due to their informational advantage. As a result, some trades that would be efficient don't occur: A buyer may value an asset more than the seller, but not enough to compensate for the informational rent the seller must pay.

This misallocation directly reduces welfare by itself, but there are indirect channels as well:

- When buying an asset, investors care about resale value. Under private information, future sellers expect to bear informational costs when selling, which depresses expected resale profits.

- The outside option of waiting to buy another asset improves, since future trades may offer the buyer a chance to extract informational rents.

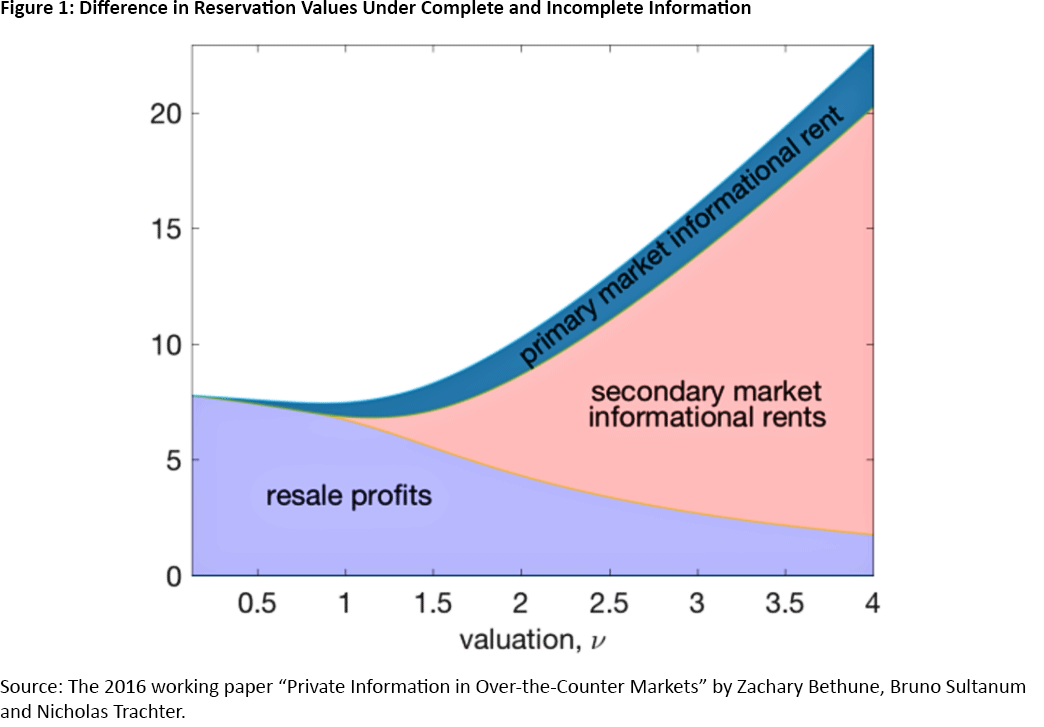

Together, these frictions make investors more hesitant, reducing the amount they're willing to pay (what economists call "reservation value"). This, in turn, discourages issuers from creating new assets and depresses overall market activity. The result is inefficiently low asset supply and trade volume. Figure 1 illustrates these indirect channels by decomposing the difference in reservation values under complete versus incomplete information. This difference is represented by the colored area.

First, notice that the area is positive: Reservation values are lower when valuations are private across all investor types on the x-axis. For low-valuation investors (such as those with ν = 0.5), the gap is almost entirely due to lower expected resale profits. For high-valuation investors (such as those with ν = 3.5), the dominant factor is a more attractive outside option: the chance to secure a better deal (and extract rents) in another trade in either the primary or secondary market. In any case, private information undermines market outcomes.

Data and Calibration

To estimate precisely how much information frictions distort real-world trading, we apply our model to the U.S. municipal bond market, which is a large, decentralized OTC market. We use a transaction-level dataset covering 2005 to 2014 and over 86 million trades across nearly 2 million different bond issues. Each observation includes information on the bond's characteristics (such as maturity date and coupon rate), the transaction itself (such as price, yield and timing) and features of the issuer (such as their geography and type).

Six parameters need to be calibrated in this model:

- The mean and variance of investor valuations

- The mean and variance of issuance costs

- The meeting rates in the primary and secondary markets

To identify the first four parameters, we use the distribution of yields across trades. For this model, yield variation arises solely from differences in how much investors value bonds and how expensive it is to issue them, so the shape of the yield distribution can be used to back out how much heterogeneity must exist in those underlying fundamentals. Meeting rates in the primary and secondary markets are calibrated by targeting the observed frequency of trades in the data.

Observed Market Outcomes

Compared to a benchmark with complete information, the model calibrated to the U.S. municipal bond market under private information predicts weaker market outcomes: Asset levels are 21 percent lower, secondary market trade volume is 77 percent lower, and total welfare declines by 4 percent.

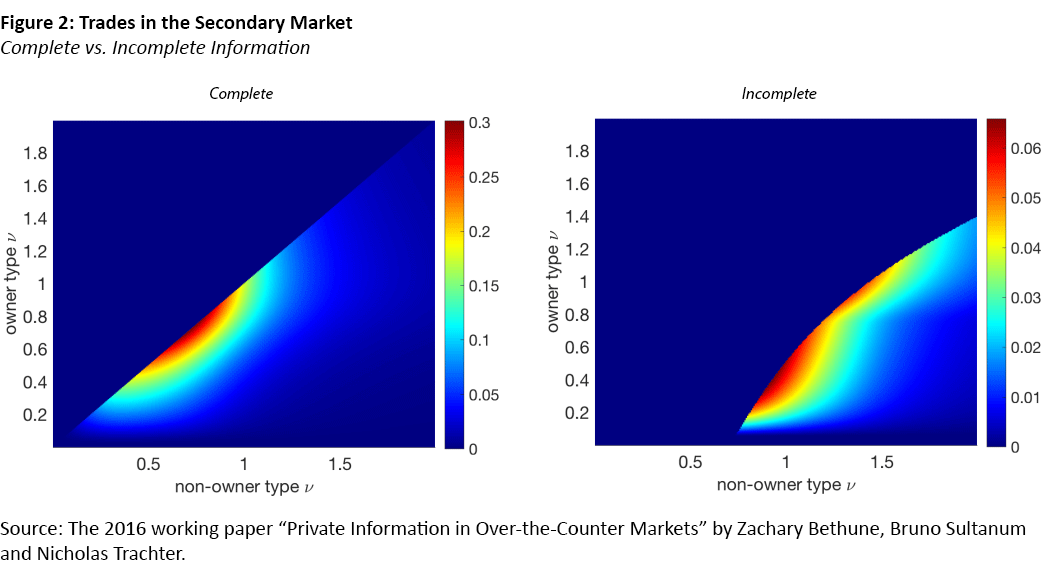

Another interesting outcome that stems from the informational inefficiency relates to the distribution of trades in the secondary market. The color scale of Figure 2 reflects the volume of trade between investors of different valuation types.

Under complete information, trades tend to occur between owners and nonowners with similar valuations (clustered around the 45-degree line), indicating a gradual movement of assets up the valuation ladder. That is, intermediate-valuation investors often act as "middlemen," reselling assets to higher-valuation buyers over time.

In contrast, under private information, this chain of trades breaks down. Owners target trades with buyers who have very high valuations, and the effect is a more concentrated and direct allocation of assets to top-valuation investors and a more passive role for middlemen.

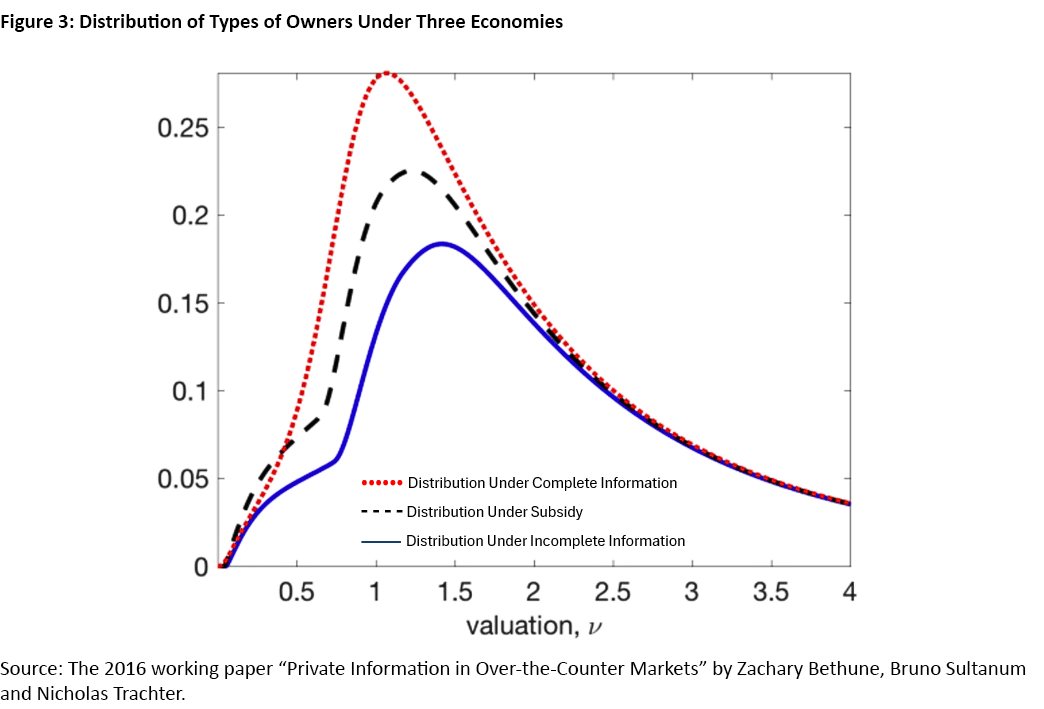

Can policy help correct these inefficiencies? Because private information discourages asset holding, a natural policy intervention is to make asset ownership more attractive. We simulate a simple policy: a lump-sum subsidy to asset holders of roughly one-third of the average investor valuation. We find that the welfare gap between the incomplete and complete information economies is reduced by nearly half as a result of the subsidy directly offsetting the costs of informational frictions.

Though substantial in effect, this simple policy is not targeted, thus encouraging even low-valuation investors to buy and hold assets when they otherwise might not do so. Figure 3 plots the resulting distribution of owners by valuation. In the world with a subsidy (black dashed line), there's an inefficiently high mass of owners of low valuation compared to a world of complete information (red dotted line). This is particularly noticeable at valuations less than 0.5. In short, while the policy boosts overall welfare, assets still aren't allocated quite as well as they would be under complete information.

Conclusion

This article highlights how private information in OTC markets creates significant inefficiencies, lowering asset supply, trade volume and overall welfare. Using a calibrated model of the U.S. municipal bond market, we estimate precisely how informational frictions distort trading incentives and ownership distributions. While simple policies like subsidies can partially offset these effects and improve welfare, they still do not achieve asset allocation efficiency.

Lindsay Li is a research associate and Nicholas Trachter is a senior economist and research advisor, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Li, Lindsay; and Trachter, Nicholas. (July 2025) "How Private Information Distorts OTC Market Outcomes." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-26.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.