What Drives Business Cycles?

Key Takeaways

- There is no clear pattern as to whether inflation tends to rise or fall during recessions.

- The apparent lack of correlation masks the fact that inflation has in fact risen and fallen with GDP over individual business cycles.

- The inconsistent historical patterns wash out on average but suggest policymakers should use data to discern the underlying drivers of any specific business cycle.

A central goal in economics is to understand the main drivers of the business cycle. Knowledge of these key disturbances and their propagation allows economists to better predict how recessions and expansions are likely to evolve, providing a crucial guide for policymakers.

The key challenge is disentangling causation from correlation. The economy consists of a vast network of interactions between consumers, firms and policymakers both domestically and internationally, making it hard to isolate the role of individual disturbances.1 Thus, pinpointing the source of, say, a decline in GDP growth is far from straightforward.

In Search of a Main Business Cycle Shock

Economists have developed numerous tools to disentangle these competing forces, extracting "shocks" from the data. To determine whether these shocks can be interpreted causally as capturing individual sources of fluctuations, economists apply a combination of economic and statistical theory to the empirical data.

In this article, we attempt to characterize the behavior of the economy over the business cycle by identifying the key driver of the observed fluctuations. We estimate a statistical model and then use econometric techniques to extract the sources of fluctuations. Our approach is based on the methodology established by economists George-Marios Angeletos, Fabrice Collard and Harris Dellas in their influential 2020 paper "Business-Cycle Anatomy." Our main object of interest is what we refer to as a main business cycle shock.

We estimate a vector autoregression — a standard statistical model used for economic and policy analysis — with macroeconomic data from the first quarter of 1960 through the fourth quarter of 2019. The estimates characterize how variables over different time horizons move together but do not identify the actual underlying drivers of these fluctuations. For example, unemployment tends to fall when GDP growth increases, but this variation could be caused by productivity improvements, increased demand or expansionary monetary policy, among other things.

We isolate the main business cycle shock using a novel econometric scheme. The idea is to find a disturbance that explains as much of the variation as possible of some target variable at business cycle frequencies, or movements over a time horizon of about two to eight years, which is usually considered the full length of historical expansions and recessions. By focusing on business cycle frequencies, the methodology avoids results driven by either very transitory or long-run movements in the data, both of which are arguably less relevant for the question at hand. We choose GDP as our target variable.

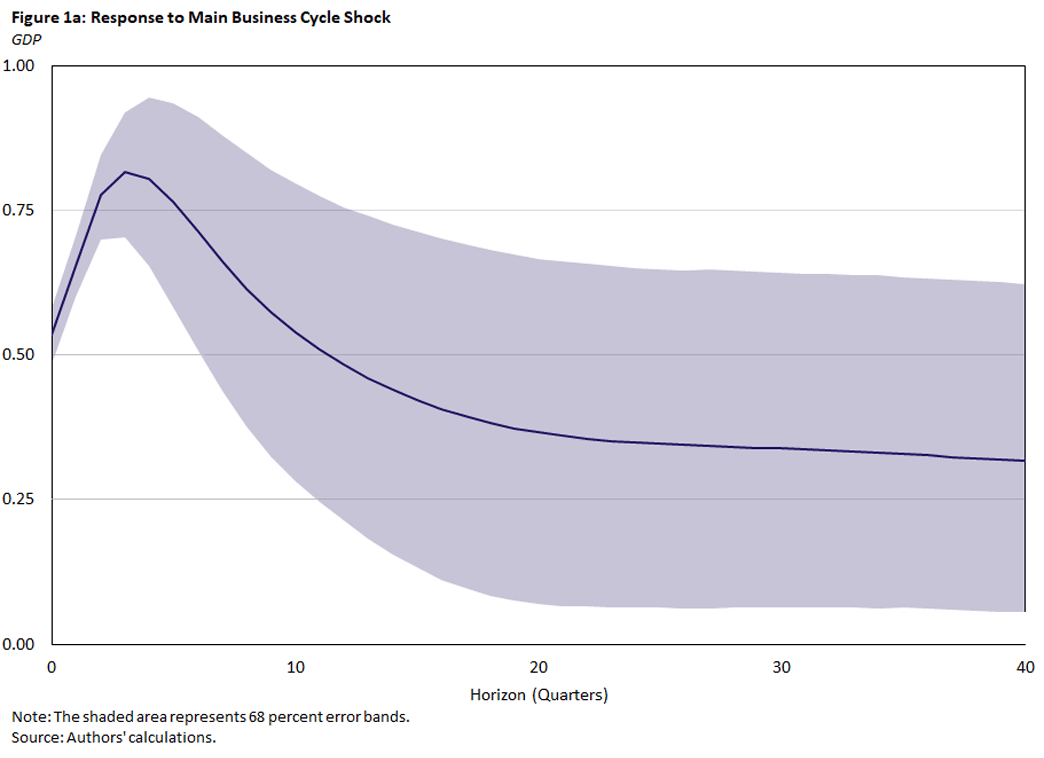

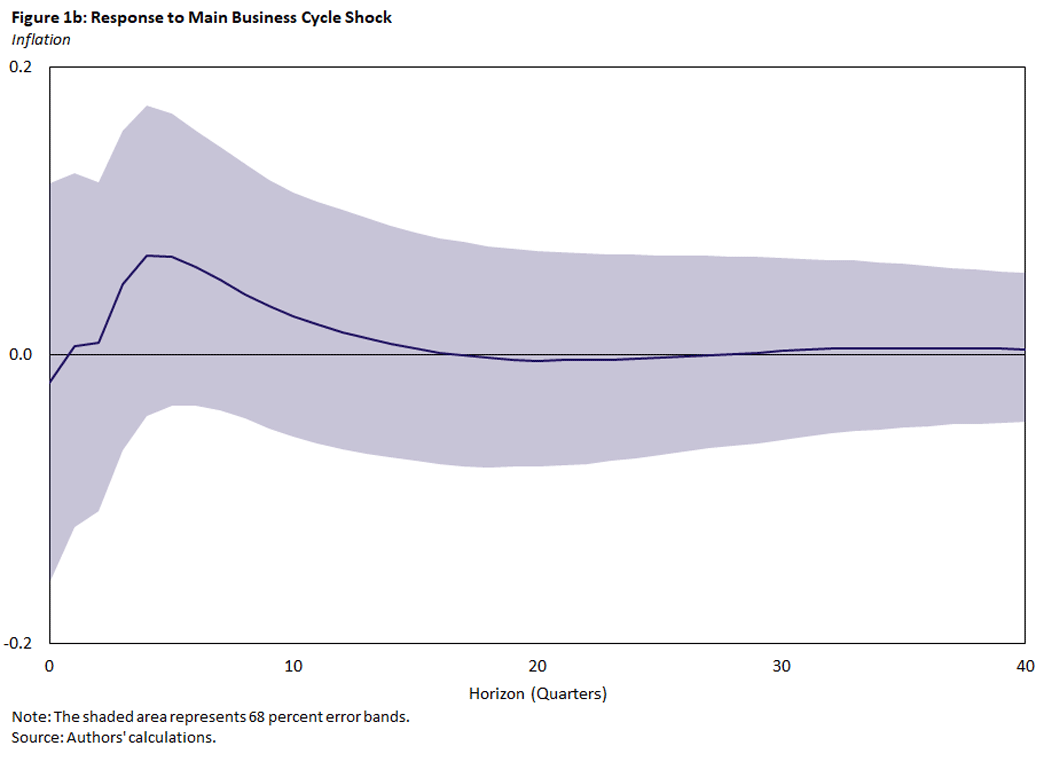

Figure 1 shows the responses (and associated error bands) of GDP and inflation to a one standard deviation increase in the identified main business cycle shock. The shock leads to a substantial increase in GDP, as would be expected. However, it has essentially no effect on inflation. On average, it explains around two-thirds of the variation in GDP but less than one-tenth of the variation in inflation at business cycle frequencies.

Given the main business cycle shock's importance for GDP fluctuations, it is tempting to view it as a single disturbance, around which we should construct a theory of how it impacts and transmits through the economy. Angeletos, Collard and Dellas argue that the lack of response in inflation contradicts (and, thus, rules out) many standard models of supply and demand shocks.

For instance, a demand-driven increase in GDP would likely raise inflation, while a surprise productivity improvement would lower inflation. However, an alternative interpretation could be that the identified shock conflates several shocks that have similar effects on output but opposite effects on inflation. Naturally, if the identified shock is not purely structural, it could potentially spell trouble for policy since its component parts would require different policy measures.

What Does the Main Business Cycle Shock Capture?

In fact, we show in a working paper on max-share identification that the main business cycle shock identified above is likely a combination of different actual drivers. In our paper, we make three different contributions and steps to make this case.

First, we derive results in statistical theory to show that the econometric methodology only isolates a single shock under conditions that are hard to satisfy in practice. Specifically, it would imply that GDP growth must respond to other disturbances in the economy (such as monetary policy surprises) in a way that contradicts both economic theory and previous empirical research.

Next, we check what the methodology yields when applied to artificial data generated from a typical macroeconomic model. The main business cycle shock in the artificial data replicates the empirical finding of a relatively small effect on inflation in actual data. In our experiment with simulated data from a theoretical model, we know how the artificial data were generated. We can thus determine whether the main business cycle shock represents a single disturbance in the model or a weighted average of diverse sources of variation. In the model with seven possible sources of disturbances, we find that the identified main business cycle shock is actually a mix of all of them. While the identification approach places substantial weight on four different disturbances, none receive more than 30 percent of the weight. In other words, the identified shock is a composite of all kinds of disturbances, which calls into question its validity as a single source driving the business cycle.

Finally, we can return to the empirical data and see if we can find evidence that challenges the interpretation of the main business cycle shock. In the previous exercise, we know the structure of the artificial economy and the nature of the shock, which we naturally do not in actual data. However, we show in our working paper that we can put a lower bound on the degree of contamination of the identified shock if we have knowledge of another potential shock present in the data. Our approach is to find a total factor productivity (TFP) news shock that explains as much of TFP as possible at the 10-year horizon and check if the main business cycle shock places any weight on this TFP news shock. We find that about one-quarter of the so-called main business cycle shock is explained by our TFP news shock. This contradicts the claim that the main driver of business cycles is effectively independent of productivity changes, which are among the sources of fluctuations that Angeletos, Collard and Dellas rule out.

In short, while the main business cycle shock summarizes how various variables tend to evolve over the business cycle with variations in GDP growth on average, we should not assign a causal interpretation to it. Instead, different forces are at play in generating business cycles.

Different Drivers of Different Cycles?

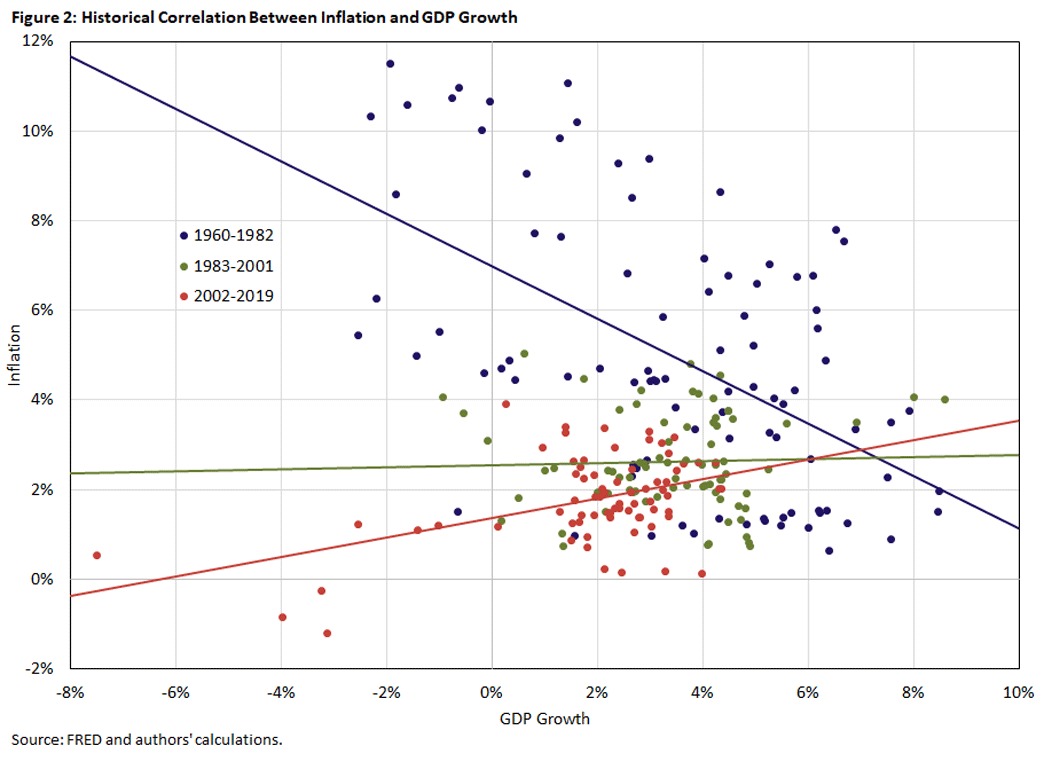

An informal way to study how different business cycles may have different drivers is to simply look at the correlation between GDP growth and inflation during different periods. A positive correlation suggests a role for demand forces, and a negative correlation suggests a role for supply forces. While this does not preclude the possibility that they could act simultaneously, it remains instructive given the key observation that the main business cycle shock has a small effect on inflation.

To that end, Figure 2 plots year-over-year inflation against year-over-year real GDP growth for the 1960-2019 period. We divide the sample into three subperiods: 1960-1982, 1983-2001 and 2002-2019.

The correlation between GDP growth and inflation changes substantially across periods:

- In the earliest subsample, the correlation is -0.54, driven in part by the stagflation in the 1970s and early 1980s.

- In the middle subsample, the correlation becomes close to zero (0.04), reflecting the relatively stable inflation during the so-called "Great Moderation."

- In the final subsample, the correlation turns positive (0.44), which is consistent with how inflation and GDP growth fell together during the Great Recession.

Therefore, even though inflation does not appear to have responded to business cycle drivers on average, it has moved substantially with individual business cycles. The degree and even the direction of these changes vary from one cycle to another.

At the very least, the substantial differences across subsamples show that the joint behavior of GDP growth and inflation has changed over time. One should thus be cautious trying to make general statements about how business cycles evolve. Given the simplicity of the exercise, we do not assign a causal explanation to the time-varying observed correlations. Besides the relative importance of supply and demand forces changing over time, other fundamental changes in the economy such as sectoral trends or the behavior of policy could be driving the differences across subsamples. Moreover, each subsample likely has multiple important sources of economic fluctuations.

Concluding Remarks

In an important contribution, Angeletos, Collard and Dellas identified a main business cycle shock that has the striking feature that it does not affect inflation. That is, conditional on this shock, inflation does not vary much over the business cycle with GDP growth on average.

However, we show in this article (based on our prior work) that the identification approach is fraught with misattribution problems. In other words, the main business cycle shock is contaminated by other shocks. Further investigation suggests roles for various drivers of business cycles whose importance have evolved over time. In any business cycle, we should therefore study the data carefully to discern the precise disturbances that may be most important at a given time to inform our forecasts and policymaking.

Liyu Dou is an assistant professor at Singapore Management University. Paul Ho is a senior economist and Thomas A. Lubik is a senior advisor, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See Paul's 2023 article "Why Are Economists Still Uncertain About the Effects of Monetary Policy?" for further discussion.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Dou, Liyu; Ho, Paul; and Lubik, Thomas A. (October 2025) "What Drives Business Cycles?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-37.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.