Trimming Off The Best Bits?

We hope you enjoy the first post in our new blog, Macro Minute. John O'Trakoun, a senior policy economist at the Richmond Fed, will take a look at the numbers beyond the headlines on the macroeconomy. John will have a new post every week, except during the Federal Reserve's blackout period on monetary policy communications in conjunction with each regularly scheduled meeting of the FOMC.

The latest monthly inflation data have been unusually elevated, leading some commentators to question whether we're headed for a period of sustained high inflation. In May, for example, CPI inflation was 5 percent year-over-year, the highest since August 2008, and year-over-year core CPI inflation was 3.8 percent, the highest since May 1992. Year-over-year PCE inflation was 3.9 percent, the highest since May 2008, and core PCE inflation was 3.4 percent, the highest since June 1992. But these recent data have been distorted by a combination of base effects because the pandemic depressed price indices a year ago and supply bottlenecks as producers struggle to meet a surge of pent-up consumer demand. To get a better sense of underlying inflation, policymakers have turned toward alternate metrics that try to remove these distortions from the data.

Policymakers have been using alternative metrics to look beyond short-term price spikes for certain goods and get a better sense of the direction of underlying inflation over the long term. One such metric is the trimmed mean PCE inflation rate, but does it risk miss anything?

One such metric is the trimmed mean PCE inflation rate, which is produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Trimmed mean inflation strips out the fastest and slowest growing prices each month, leaving behind a less noisy measure of core inflation. In May, the annual trimmed mean PCE inflation rate was 1.9 percent, below the Fed's 2 percent target and below the 2.1 percent observed in February 2020.

"Just as we wouldn't want to ignore the first confirmed cases of a viral infection in the early days of a pandemic, we might not want to ignore rising prices of some goods and services if they signal that a broader inflationary process lies ahead."

But does this trimming process miss anything? What if inflation spreads like a pandemic, starting off in individual price categories before spilling over and "infecting" the prices of other goods and services? Just as we wouldn't want to ignore the first confirmed cases of a viral infection in the early days of a pandemic, we might not want to ignore rising prices of some goods and services if they signal that a broader inflationary process lies ahead. In the early stages of inflation, rapidly growing prices might initially be chopped off by the trimmed mean, which could make trimmed mean PCE inflation a lagging indicator of inflation pressure.

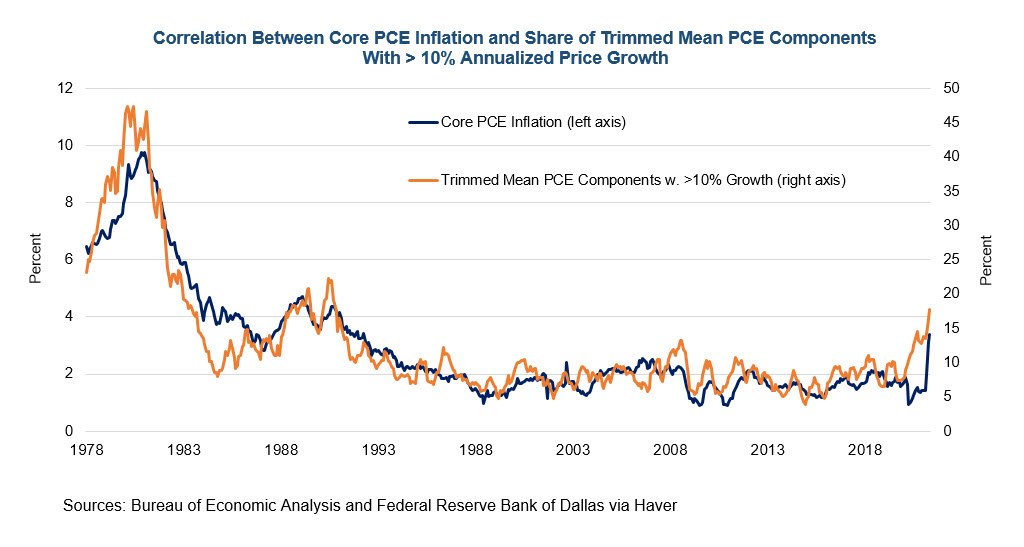

But some of those fast-growing prices might escape the trimming process, falling just under the cutoff threshold. These prices could send important signals about inflation, so the Dallas Fed provides additional information about the distribution of component price increases along with the top-line numbers. In May, there were a higher fraction of price changes at the faster growing end of the distribution. The share of included prices growing 0 to 2 percent on an annualized basis fell to 11.7 percent of spending, compared to 13.7 percent in April. The share of prices growing faster than 3 percent rose to 49.1 percent of spending, up from 43.6 percent in April. Prices rose 10 percent or more for 17.8 percent of spending, remaining elevated following the 19.5 percent share observed in April. Over a longer horizon, there's a strong correlation between core PCE inflation and the share of trimmed mean PCE components that have higher than 10 percent annualized price growth. That share has been rising since the onset of the pandemic. (See chart below.)

So, beneath the surface of May's modest trimmed mean PCE numbers, there are signs that underlying inflation may indeed have moved up somewhat. In this period of historically high policy support and recovery from an unprecedented pandemic, all eyes will be on the coming months' inflation data.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.