Rising Unemployment Risks: Suddenly, Then Gradually

In The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway wrote, "How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly." The risk of similar abrupt changes also exists for the labor market. For example, during the COVID-19 recession, economist Torsten Sløk said, "Clearly with the unemployment rate, we went up the elevator, and we're definitely going down the escalator." More recently, in the September 2025 post-FOMC press conference, Chair Jerome Powell said, "The concern is that if you start to see layoffs ... there won't be a lot of hiring going on. So that could very quickly flow into higher unemployment." In this week's post, we look at how asymmetric unemployment rate movements have unfolded during previous recessions.

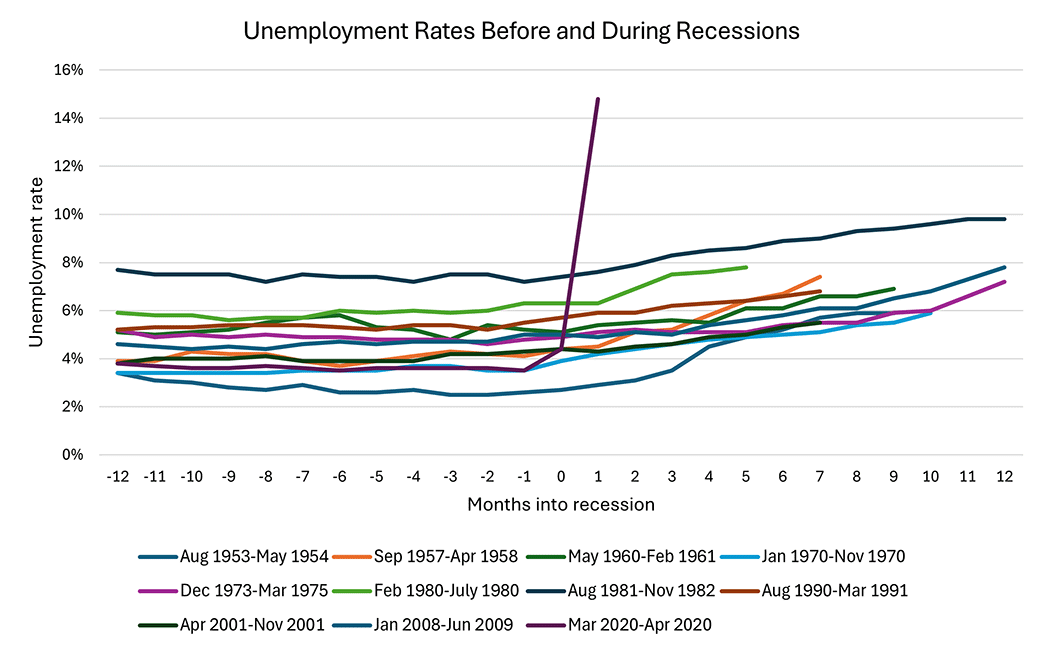

Figure 1 below plots the unemployment rate during the past 11 recessions. The COVID-19 recession jumps out as an outlier in terms of how steeply the unemployment rate rose. Unemployment during that period was characterized by an elevated share of pandemic-driven "temporary layoffs," which reverted relatively quickly as workers were called back.

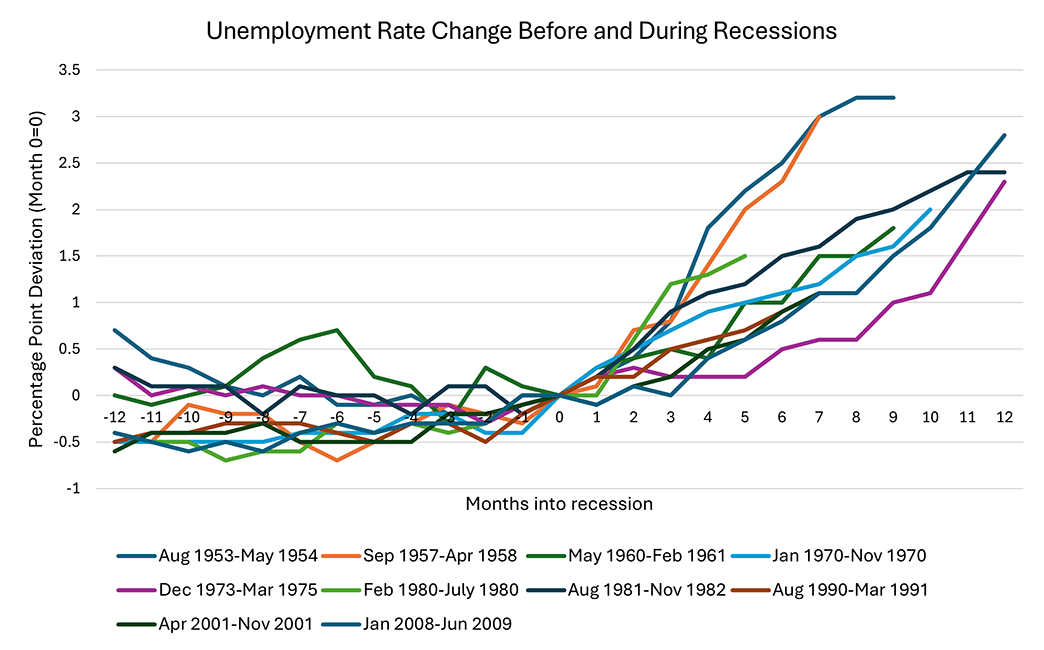

Figure 2 below omits the COVID-19 recession and normalizes the unemployment rate during the first month of the recession to zero. The asymmetry in unemployment rate increases is evident: In the 12 months leading up to a recession, the unemployment rate basically moves sideways. When the recession hits, the unemployment rate rises steeply.

What explains the sharper rise in the unemployment rate during recessions? As Chair Powell alluded to in the press conference, it stems from an interaction between two factors:

- Hiring (or job matching), which influences flows from unemployment to employment

- Separations (such as layoffs), which influence the flow of workers from employment to unemployment

During a recession, when the labor market sees a mix of lower job matching and higher layoffs, the combined impact of the two forces can drive a steep change in the unemployment rate relative to its pre-recession trajectory.

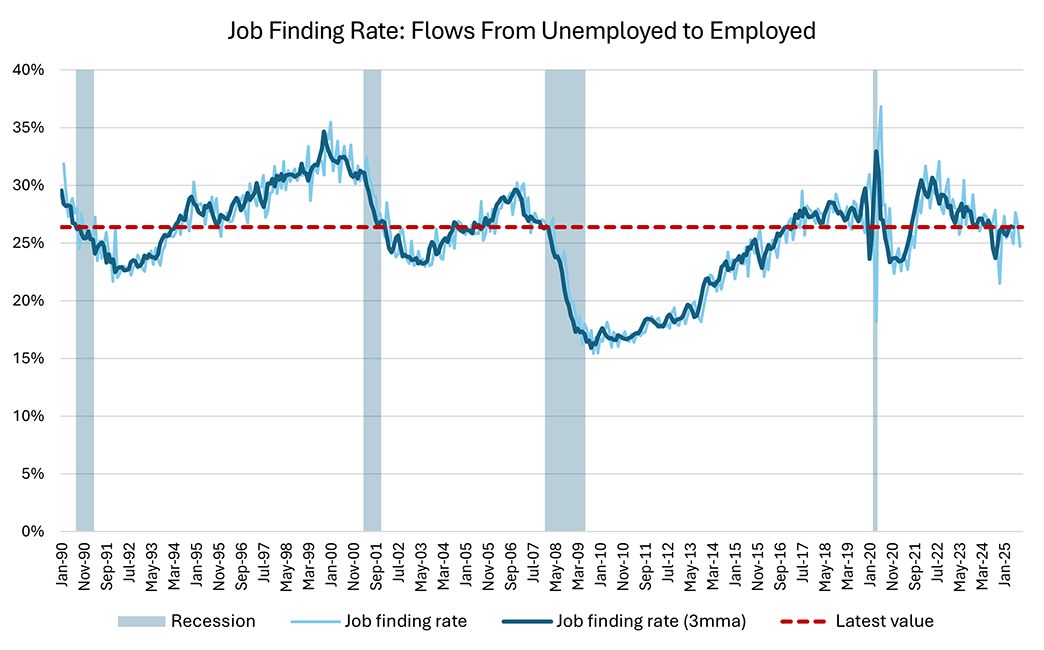

What do the latest data say about the current state of these two forces? Figure 3 below plots the job finding rate, which is the number of people who transitioned from unemployed to employed in each month expressed as a share of the prior month's unemployment level. The red dashed line indicates the most recent three-month moving average of 26.4 percent in August 2025.

The figure indicates that current job finding rates are already similar to recessionary levels observed in 1990, 2002 and 2008. While the 2008 recession shows that the job finding rate could fall much lower if the economy is hit by a big negative shock, the fact that today's job finding rates are already at low levels suggests there may be less room to fall in a more moderate economic slowdown.

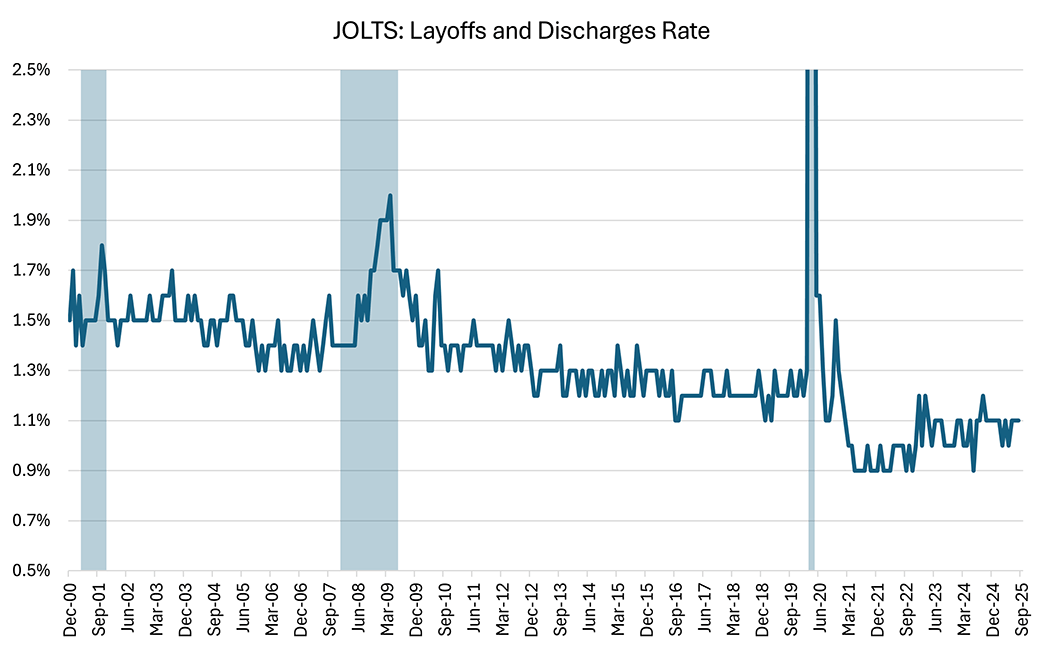

As for separations, the latest data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, suggest that the layoff rate of 1.1 percent in August is historically low, which means it may be prone to a larger increase if it returns to its historic average. (See Figure 4 below.)

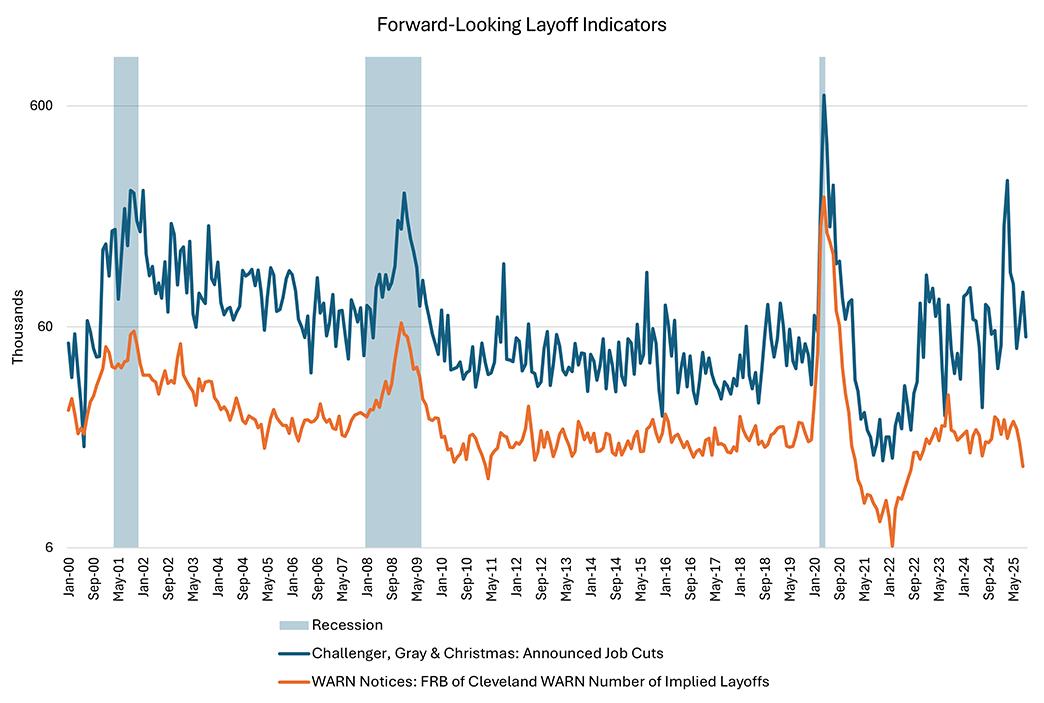

However, layoff announcements can give some advance notice of employers planning job cuts. Figure 5 below shows layoff announcements compiled by outplacement services providers Challenger, Gray & Christmas (blue line) and a national level index published by the Cleveland Fed based on Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act filings (orange line). The WARN Act requires larger employers to notify affected workers at least 60 days before a potential mass layoff.

September 2025's level of 54,064 announcements compiled by Challenger, Gray & Christmas is the lowest in three months and within the range observed from 2022 through 2024. And the latest observation from the Cleveland Fed index suggests layoffs are lower compared to the past three-year average, as well as the decade before the pandemic, a situation that Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin has called a "low hiring, low firing" environment.

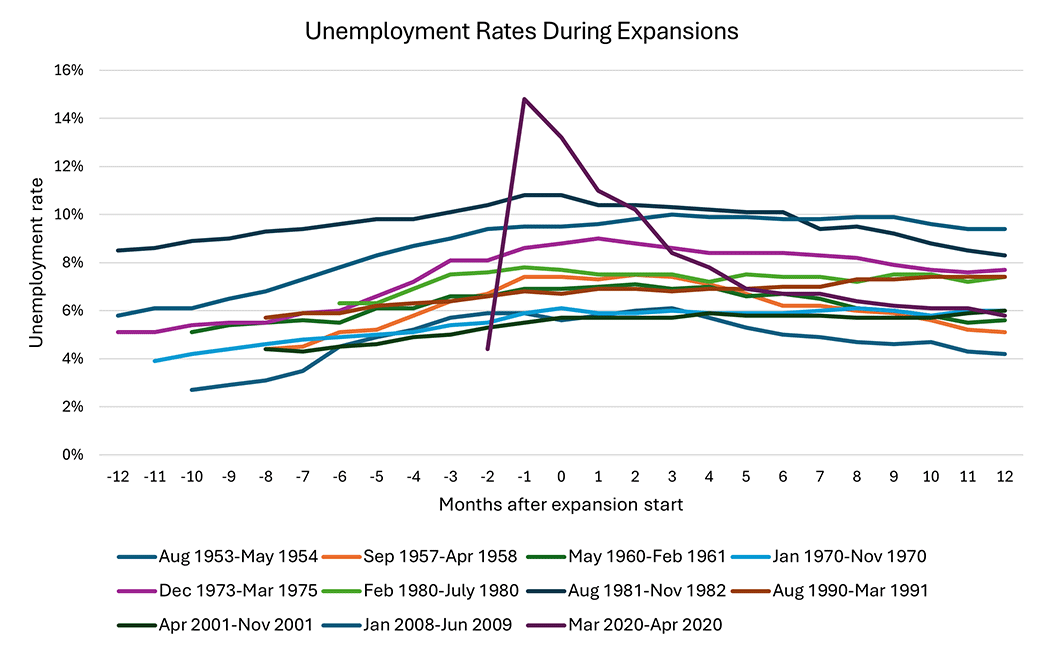

Having discussed the rise in unemployment rates in a recession, what happens during a recovery? Figure 6 below plots unemployment rates in the year following recessions. While there is variation across recessions, the first year of the expansion generally sees a gradual recovery in the unemployment rate (that is, an escalator ride down).

Academic researchers have identified systematic patterns to the behavior of the unemployment rate during expansions. For example, economists Robert Hall and Marianna Kudlyak find that U.S. unemployment declines at a smooth, slow and regular pace during recoveries. Economists Alisdair McKay and Ricardo Reis find that employment contractions are shorter and more rapid compared to expansions.

This post shows that the unemployment rate in previous recessions increases sharply relative to the pre-recession period of stable unemployment rates. Recent low levels of job finding rates could indicate that there's less room for job finding to fall compared to prior recessions, while low levels of layoff announcements don't appear to indicate elevated risk of a sudden rise in separations. Following recessions, the asymmetric behavior continues, with the unemployment rate typically following a smooth and gradual recovery relative to the recessionary rise.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.