Building the Aerospace Cluster in South Carolina

At the time of the Wright Brothers' first successful powered flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1903, few recognized just how big the industry would become or how transformative the location decisions of aircraft companies would be to regional economies. Today, aircraft manufacturing generates a tremendous amount of economic activity in clusters such as the Puget Sound area of Washington, Southern California, and St. Louis, Mo. — and, more recently, in South Carolina. State governments that recognize the tremendous economic value that aircraft manufacturing can bring their communities are actively courting such plants to bolster their aerospace clusters.

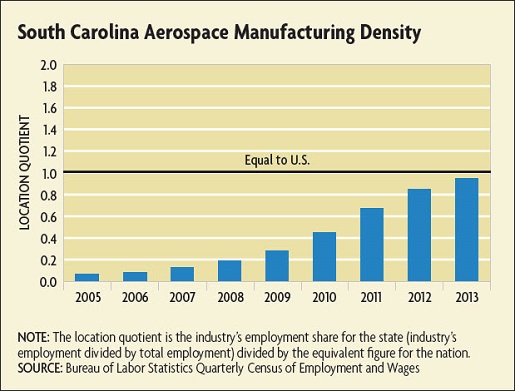

Boeing's 2009 decision to locate a 787 final assembly plant in North Charleston made South Carolina one of only two states with a large civilian aircraft final assembly plant. (Alabama will make it three when Airbus completes its A320 family assembly plant in Mobile later this year.) It is just the third site worldwide that is capable of assembling and delivering twin-aisle aircraft. Boeing's two decisions — first, to pursue the 787 project, and second, to locate a final assembly plant in South Carolina — resulted in a "big bang" for aerospace manufacturing in the state, creating an industry cluster out of virtually nothing.

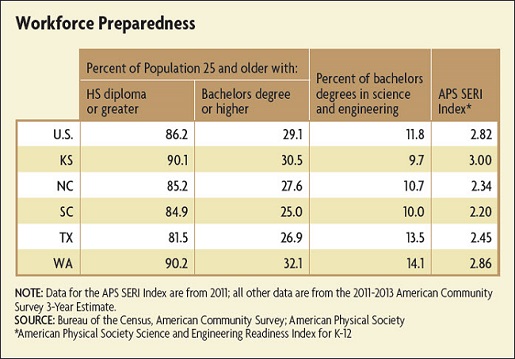

Inevitably, when a cluster grows so rapidly in such a short period of time, there are bound to be growing pains. The area around North Charleston, where the 787 assembly plant is located, is already suffering from shortages of skilled labor. And a Chamber of Commerce-sponsored report on the outlook for skills gaps in the region paints a challenging picture. How quickly South Carolina is able to build up its human and capital infrastructure will go a long way toward determining how much bang the state will get from its incentive bucks. This article explores why aircraft manufacturing facilities are such attractive economic development targets, and how well positioned South Carolina is to maximize the return on its economic development investment in the aerospace manufacturing cluster.

Targeting Aerospace Clusters

Targeting industry clusters is a common regional development strategy, and for good cause. Economic theory suggests there are considerable benefits to having similar businesses agglomerating in a region. Most notable among the benefits are the synergies and efficiencies that clustered firms can derive from attracting labor with specialized skill sets to the region, as well as inputs common to the production process. Moreover, productivity within the cluster increases as knowledge "spills over" from one industry participant to another.

An aircraft final assembly plant falls into a more narrowly defined industry cluster known as a traded, or exporting, cluster. As opposed to a non-traded industry cluster, where the majority of the industry's output is consumed locally, traded industry clusters sell the majority of their output outside the region.

State and local economic development entities have limited funds, so they strategically focus those resources toward industries, or firms within industries, that will provide the highest return on investment and limited risk. Two of the most important criteria in decisions to deploy economic development dollars are the potential for strong growth over the long run and the creation of high-paying, high-value-added jobs.

Growth Potential

With regard to the first investment criterion, potential for growth, the outlook for manufacturing of large civilian aircraft is quite favorable. The demand for these aircraft is a function of the demand for air transportation. As the global economy becomes ever more connected, and consumers and businesses in developing economies become more affluent, demand for air travel is expected to grow steadily for decades to come. The International Air Transport Association forecasts that the number of boarded passengers worldwide will increase from roughly 3.3 billion in 2014 to 7.3 billion by 2034. That is an average annual increase of 4.1 percent over the 20-year span.

Increasing air travel means stronger demand for civilian aircraft. Moreover, with expectations that air transportation will be increasing in all regions, the demand for commercial jet liners is geographically diverse. The first 787 that rolled out of Boeing's North Charleston final assembly plant was destined for Air India, and the vast majority of that platform's orders are coming from foreign-owned and operated airlines. As of the first quarter of 2015, more than 70 percent of Boeing's 787 backlogs were destined for foreign carriers. More geographic diversity in a company's orders limits its exposure to economic downturns in one region or another.

In addition, producing large civilian aircraft is a very complex undertaking that requires a highly specialized, high-tech set of inputs. Thus, civilian aircraft manufacturing is a subset of a larger and rapidly growing cluster of goods-producing and service-providing industries: aerospace. Components of the broader aerospace manufacturing cluster include, among others, aircraft and parts manufacturing (civil and defense related); search, detection, guidance, and instrument manufacturing; and guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing.

All of these manufacturing pursuits have something in common: powered flight. As a result, the core components of aerial vehicles are made up of precision parts and specialized materials that are held to a higher standard of quality. This is because the movements are more complex, and the costs of component failure so much higher, for vehicles that leave the ground. Thus, many of the materials, parts, or components used in civilian aircraft can be adapted for use in other aerospace pursuits (military aircraft or unmanned aerial vehicles, for example) and vice versa.

So in terms of economic development recruitment, Boeing South Carolina certainly offers high growth potential in a fast-growing manufacturing cluster. Moreover, given the level of investment the company has made into its facilities in the state, there is virtually no risk that the company will close the facility in at least a generation.

Job Quality

The second key criterion for investing economic development dollars is the number and quality of jobs being created by the targeted cluster. On this score, the aerospace manufacturing cluster ranks high as well.

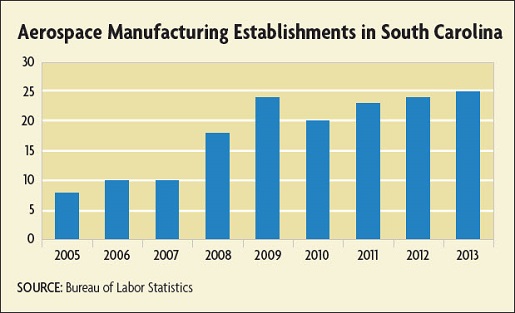

Employment growth in aerospace product and parts manufacturing was a big boost to South Carolina's manufacturing sector, which was particularly hard hit during the Great Recession. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that there were only around 450 workers employed in the state by firms classified in the aerospace product and parts manufacturing industry in 2005. By 2013, that number had increased more than 14-fold, to roughly 6,500 workers. Employment growth in the state began to increase rapidly in 2008 when Boeing started to buy out some of the companies and joint ventures that were supporters of the 787 project in North Charleston and consolidated those operations.

Those new jobs were particularly welcome during the first two years coming out of the trough of the jobs recession. Aerospace product and parts manufacturing was responsible for approximately 23 percent of all net new manufacturing jobs created in the state between 2010 and 2012, despite accounting for only 1.5 percent of the state's total manufacturing job base.

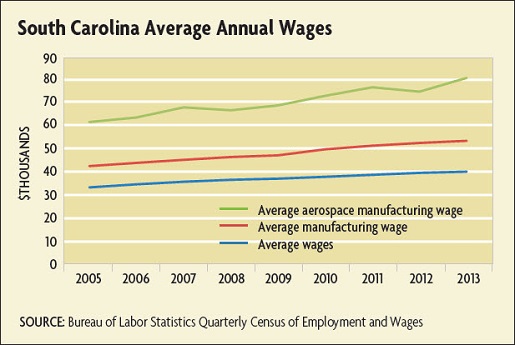

And the jobs created in aerospace manufacturing are well compensated. The average annual wage for workers in South Carolina's aerospace product and parts manufacturing industry was $80,757 in 2013, which is 52 percent higher than the average manufacturing wage in the state and more than twice the state's economy-wide average wage. Moreover, average wages are increasing faster in the industry than in manufacturing or across the state's economy (see chart 1).

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.