Show and TEL: Are Tax and Expenditure Limitations Effective?

More than half of the states in the United States are subject to some kind of limitation on their ability to raise taxes, spend money, or incur debt. Most states, at the same time, impose similar constraints on their local governments. These measures are commonly referred to as tax and expenditure limitations (TELs). TELs are part of a larger set of fiscal rules aimed at curbing the budget process with the objective of constraining decisions made by governments. Recent research has examined the effectiveness of TELs in achieving their intended objectives. This research mainly attempts to disentangle the effect of TELs on fiscal policies, policy outcomes, and economic performance. The findings are mixed: While a few studies assert that TELs do restrain governments, others hold exactly the opposite. Some research work even finds that TELs have been detrimental to the states' financial position.

Why Do TELs Exist?

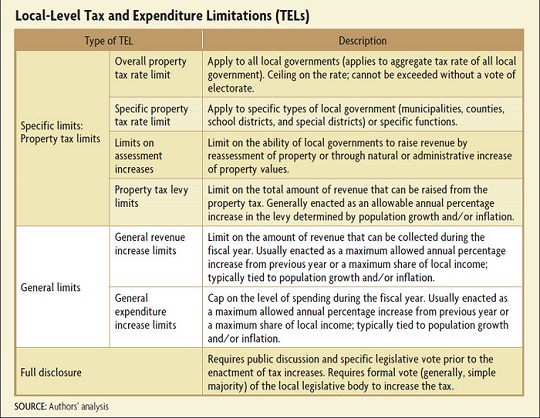

State and local government budgets are constructed following certain fiscal rules defined in advance. While some of these rules define specific guidelines that should be obeyed throughout the budgeting process in order to guarantee fiscal transparency and accountability, others explicitly restrict the size of the government. Among the latter, TELs are perhaps the most widely used among state and local governments. Specifically, TELs establish a set of rules typically defined in terms of limits on the growth of tax revenues, spending, or both, with the ultimate objective of constraining the growth in the size of government. Other fiscal rules, such as balanced budget provisions and debt limits, do not necessarily intend to limit the size of government.

James Poterba of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology argues that the role of TELs and fiscal rules in general can be characterized by two contrasting views: the institutional irrelevance view and the public choice view. The institutional irrelevance view claims that budgetary institutions simply reflect voters' preferences and do not directly affect fiscal policy outcomes. States politically dominated by electorates manifestly opposed to a strong government presence in the economy would tend to limit government revenue and expenditure regardless of the existence of TELs, so in this sense the rules will necessarily be nonbinding and simply viewed, in Poterba's words, as "veils, through which voters and elected officials see, and which have no impact on ultimate policy outcomes."

The public choice view, on the other hand, supports the idea that fiscal rules can constrain fiscal policy outcomes. This view implies that politicians and governments, driven by self-interest motives, choose policies biased toward higher levels of taxes and expenditures, and these choices do not necessarily benefit the public interest. In this context, fiscal limits, such as TELs, can potentially limit the set of alternatives that politicians may choose from and, consequently, influence policy outcomes. Even in this case, however, it is not clear which rules are effective and how the system should be designed.

Moreover, the implementation of TELs is challenging because it is subject to the well-known principal-agent or delegation problem. The idea is that once voters (the principals) set the limits through TELs, the implementation is ultimately delegated to politicians or government officials (the agents), who, as stated earlier, may prefer larger levels of taxes and spending. In order for TELs to achieve their intended objectives, voters should be able to follow the implementation of the rules and monitor governments' current and future actions. But such monitoring is not only costly but also imperfect. As a result, governments driven by self-interest motives might end up adopting alternative and circumventing actions that will partially offset the effects of the limitations. For instance, governments may strategically change their revenue structure and increase reliance on income sources not subjected to limitations.

State-Level TELs

As of 2010, some 30 states have enacted some kind of tax or expenditure limitations, of which 23 have only spending limits, four have only tax limits, and three have both spending and tax limits. The institutional differences across state-level TELs include the method of codification, approval procedures, type of limit, specification of the growth factors, treatment of surplus revenues, and provisions for overriding or waiving the limit. These institutional differences make some TELs more restrictive and binding than others.

Differences in the means of codification translate into differences in effectiveness. While in some states TELs are statutory, in others they are codified in the state constitutions. Statutory TELs can be more easily modified or rescinded by the legislature, so constitutional TELs are generally considered more effective tools to restrain the government's size.

The methods of approving TELs also vary across states. In general, one of the following procedures is used: citizen initiative (or referendum), legislative proposal, or constitutional convention. These alternatives are not mutually exclusive and a combination of the three may also be observed. For instance, the approval of a citizen initiative may require the approval by the legislature as well.

Differences in the type of limitation are also, of course, highly significant. States establish limits on expenditures, revenues, appropriations, or a combination of them. In principle, since most states also have balanced-budget provisions in place, expenditure limits should be largely equivalent to revenue limits. In practice, however, revenue limits are more restrictive than spending limits, mostly because spending limits do not generally affect all spending categories, and the spending limits usually apply only to general fund expenditures, not special funds. The latter means that the legislature can always avoid the limits imposed by TELs by transferring funding allocations from one fund to the other. The limits on appropriations are typically set as a percentage of the general revenue estimates.

State TELs vary in how they allow tax revenue or spending to grow. TELs generally allow tax revenue or spending to increase according to some combination of three variables: personal income growth, population growth, and inflation. Since personal income growth is generally higher than inflation or population growth, limits based on the former factor are considered less restrictive.

The treatment of budget surpluses is another area of variation. Some state TELs include refund provisions that establish precisely what to do in case of a surplus. The most restrictive TELs require state governments to immediately refund any surplus to taxpayers through rebates. Others mandate governments to use the surplus in other ways such as the retirement of debt, the establishment of rainy day or emergency funds, or budget stabilization funds.

Most TELs also include extraordinary procedures to override the constraints. These procedures include, for instance, a specification of majorities required to change the tax or spending limits. More stringent TELs require supermajorities in typically smaller bodies (such as legislative) and/or simple majorities in larger bodies (such as the electorate).

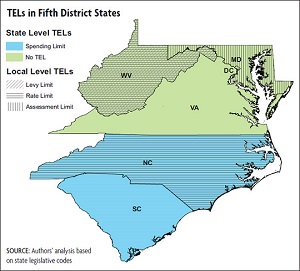

TELs in the Fifth District

North Carolina and South Carolina are the only two states in the District in which the state-level governments are subject to TELs. In 1991, North Carolina adopted a statute that limits general fund operating budget spending to 7 percent of the forecasted total state personal income for that same fiscal year. South Carolina's spending limit is mandated by the state constitution, which limits the annual increase in appropriations based on an economic growth measure that is determined by the general assembly. The current formula prescribes that an increase in appropriations be limited to either the prior fiscal year appropriations multiplied by the three-year average growth in personal income or 9.5 percent of total personal income reported in the previous calendar year, whichever is greater.

A larger number of Fifth District states impose TELs at the local level. In North Carolina, counties and municipalities are subject to property tax rate limits. Maryland also imposes property tax limits; however, the limit is on the assessment increase rather than on the rate. West Virginia has the most potentially restrictive set of TELs in the District, with limits on the overall property tax rate as well as specific property tax rates (for agricultural land, for example) and the amount of property taxes that can be collected. South Carolina and Virginia impose no TELs on their municipalities. The District of Columbia limits annual increases in the total property tax levy. (See map below.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.