Measuring Income Inequality and Economic Mobility

Measures of income inequality and economic mobility have been gaining the public's and policymakers' attention in recent years. This is due, in part, to a long-run trend of increasing income inequality in the United States since 1979. According to recent data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), after-tax average household income for the poorest 20 percent of the population grew by 46 percent from 1979 to 2013, while the middle 60 percent saw a gain of only 41 percent over this period. The trend is even more striking with regard to the so-called "1 percent": From 1979 to 2013, the CBO reported growth in household income of 192 percent for the top 1 percent of households.

It seems likely that the fast growth of income accruing to the top 1 percent of households has sharpened the focus on income inequality. These figures do not necessarily translate into impoverishment for those at the lower end, however: Despite the growing disparity in income among households, average household income, adjusted for inflation, has grown across all of the commonly reported income groups reported by the CBO analysis.

The interest in income inequality may also stem from more recent economic trends that have included relatively healthy growth in employment accompanied by only modest gains in average wages. For example, while employment has grown an average of 1.6 percent nationally per year from 2010 to 2015, real wages have grown by only 0.8 percent over the same period. (See "Will America Get a Raise?") These trends are particularly important because labor income accounts for a larger share of income for households in the middle 60 percent of the distribution, ranging from 75 to 82 percent of average market income (that is, income from sources other than government transfer programs). In contrast, the poorest one-fifth of households earned 66 percent, and the richest one-fifth earned 65 percent, of their income as labor income in 2013.

Measuring Income Inequality

Assessing the changes in income distribution in the nation, or in states or metro areas, starts with an understanding of how the different government data sources define income. Common data sources include statistics drawn from tax return data available from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the U.S. Census Bureau's "money income" series, and estimates from the CBO — but there are important differences.

Starting with the narrowest definition, the IRS measures pretax income derived from federal tax return data. While these data have the advantage of more complete coverage for the highest-income households, and therefore are favored for reviewing trends of the top 1 percent, they suffer from the exclusion of important government transfers and under-representation at the bottom of the distribution because many families are not required to file tax returns. The Census data include pretax household income plus government cash transfers such as Social Security, unemployment insurance, and cash public assistance. These additional elements of income tend to disproportionately benefit households at the lower end of the distribution. Finally, the broadest measure is the net after-tax income data provided by the CBO, which use more detailed tax record information combined with demographic characteristics and income data from the Census, but also include government transfers as well as capital gains income and some imputed noncash sources of income, and subtract direct and indirect federal taxes. These different measures can generate somewhat different conclusions about the trends in income inequality — for the magnitude of change, if not the direction.

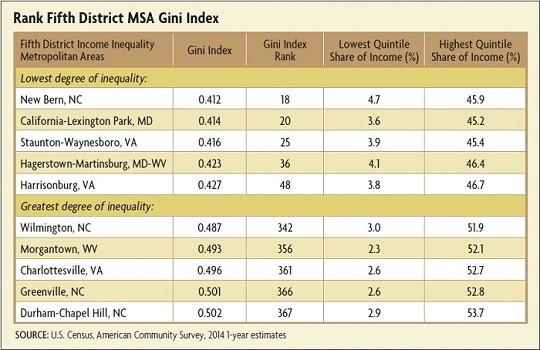

The standard measure of income inequality is the Gini index (sometimes called the Gini coefficient). The Gini index, developed in the early 20th century by Corrado Gini, summarizes the entire distribution of income in a single metric ranging from zero to one. A Gini index of zero would result if income were distributed equally across all groups, while a value of one indicates that all of the income is received by the highest-income group, with none going to the lower-income groups. This metric can be used to compare a single region over time or to compare geographic units such as states or countries.

The Gini index calculated from the CBO's broader definition of net after-tax income is lower than the same index based on before-tax income. Even so, the trend over time is very similar between the different measures. In 1979, the Gini index based on after-tax income was 0.36, but by 2013, it had risen to 0.44. The effect of government transfers and the progressivity of the federal tax system help to reduce income inequality. The Gini index on market income, which excludes these effects, was 0.60 in 2013. This higher value (more unequal distribution of income) is similar to estimates that economists have generated on pretax measures of income derived from federal income tax return data. (See chart below.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.