Land-Use Regulations: A View from the Fifth District

Land and housing can be costly in a city or region for a number of possible reasons. Places with recreational or cultural attractions or other amenities draw population so the demand for housing and, consequently, land is high in those areas. Prices could also be high at some locations if the supply of land is constrained by the geography. In some areas, however, the price of land is high as the result of heavy land-use regulations (LURs), which restrict the availability of houses.

LURs are often justified on the basis that they intend to correct for market imperfections. Their cost-effectiveness has been questioned by many researchers, however. Regardless of their merits, the use of LURs by local governments has become widespread and their intensity has been steadily increasing.

Understanding the impact of LURs is extremely important, but at the same time challenging. To the extent that LURs reduce housing availability and increase housing prices at certain locations, they may discourage productive labor migration from taking place. Moreover, since LURs tend to affect different interest groups in conflicting ways, some researchers simply view LURs as the outcome of a local political process. Due to the complexity of the large number of local rules in place, their consequences are still not completely understood.

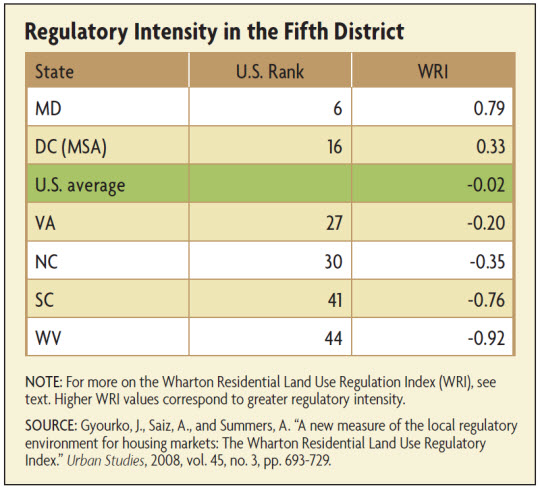

In the Fifth District, the importance and the role played by LURs is far from homogeneous. While LURs are notably constraining in places like Washington, D.C., and some parts of Maryland and Virginia, they are less important elsewhere. This article examines the determinants of LURs, reviews some of their consequences, and looks at their prevalence in the Fifth District.

What Are LURs and How Are They Quantified?

Urban life and the concentration of people and activities in a region have a number of advantages. High densities, at the same time, generate nuisances; zoning and other LURs are among the policy alternatives frequently adopted by localities to address the negative external effects associated with density. But the proliferation of LURs in the United States, a process that gained strength in the 1960s, has imposed substantial pressure on land costs, constrained the expansion of housing supply, and generated excessively high housing prices in some cities.

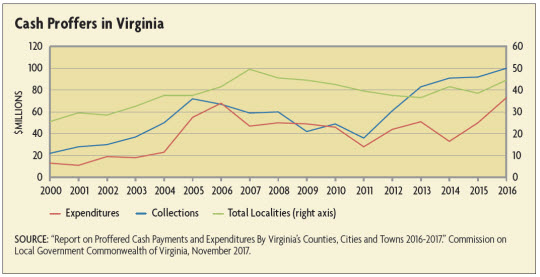

Cities regulate the use of land in different ways. The term land-use regulations generally encompasses all the rules and policies that set the standards for the development of land and housing construction. These regulations include zoning ordinances that determine how the land should be used (commercial, multifamily, or single-family use) and the type of structures that can be built. They also include rules that establish how the structures should interact with the surrounding area, such as minimum lot size requirements, maximum height of buildings, maximum units that can be placed on a lot, minimum setbacks for a building from its neighbors, and off-street parking requirements. Other frequently observed regulations are demands for developers to pay for infrastructure (roads, sewers, schools) and historic preservation policies. Together they constitute a fairly complex set of rules not only because they cover many different dimensions, but also because they generally involve the participation and intervention of several enforcement and control authorities. Making sure a particular development complies with all the regulations may result in a lengthy approval process for the construction of housing, raising the overall cost of the development.

Due to the complexity of land-use policies, it becomes difficult to precisely quantify their stringency. One of the most recent and comprehensive measures of the intensity of LURs in the United States is the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulation Index (WRI). This index, developed by Joseph Gyourko and Anita Summers of the University of Pennsylvania and Albert Saiz of the MIT Center for Real Estate, is based in part on the results of a national survey of local LURs conducted across a large number of municipalities. The main purpose of the index is to characterize the regulatory environment in a community.

The questions asked in the survey cover three different areas related to land-use policies. The first set of questions attempts to identify the authorities involved in the regulatory process. The second set asks about the type of regulations most commonly observed in the area (limits on new construction, minimum lot requirements, affordable housing requirements, open space requirements, or requirements to pay for infrastructure). The final set of questions focuses on the outcomes of the regulations. They ask, among other things, whether the cost of housing development has increased or if projects are delayed or take longer to be completed.

The WRI combines this survey information with other data sources that include local environment and open-space-related ballot initiatives, and data on legal, legislative and executive actions involving land-use policies at the state level. In this way, the index captures the overall intensity of LURs in a specific local area. The WRI index is one of the most frequently used indicators of regulatory stringency in the academic literature; some examples will be discussed below.

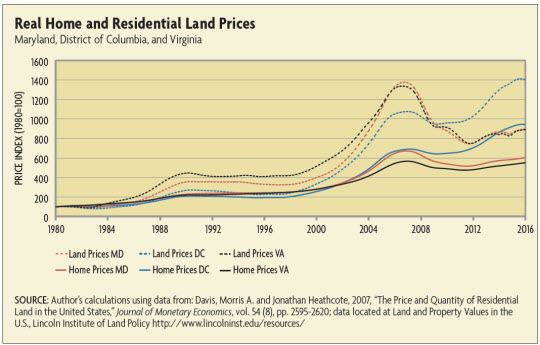

Another approach is to look at the evolution of the main cost components of housing: land and structures. In a 2003 paper, Edward Glaeser of Harvard University and Gyourko suggest that the stringency of the regulatory environment in a community could be assessed by comparing the difference between the local home price and the cost of housing construction (that is, the cost of the structures built on the land) per square foot. The idea is that LURs impose an additional cost to housing development, so the difference between housing prices and material costs would in part capture the cost of the regulations. Empirical evidence shows that in the United States, the gap between the two has been steadily increasing since the 1980s, concurrent with the rise in adoption of LURs. The increasing gap is mostly driven by home prices rising more rapidly than material costs throughout the period. The latter seems to suggest that housing availability may be constrained by the high development costs imposed by local barriers to land development rather than by changes in the cost of the structural component of homes.

Developable Land and Local Housing Supply

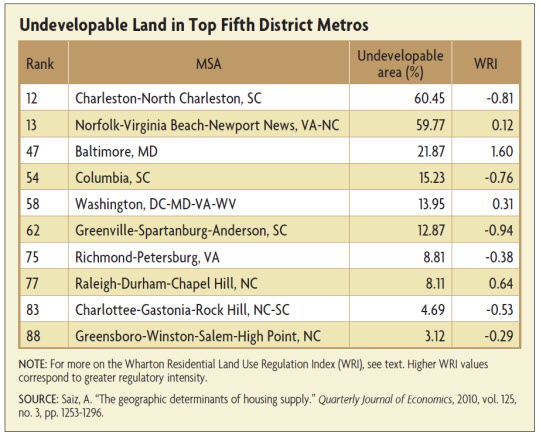

The supply of land, and therefore its price, can be affected by a locality's geographic conditions. In a 2010 article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Saiz estimates the percentage of undevelopable land in 95 U.S. metropolitan statistical areas (these are MSAs with population larger than 500,000). His approach incorporates topography and heavily relies on data from satellite images. It consists basically of calculating first the area within a 50-kilometer radius of the geometric center (or centroid) of each MSA and then removing the area lost to oceans, internal water bodies and wetlands, and the proportion of land with a slope in excess of 15 degrees. He later compares the percentage of developable land and the level and changes in housing values for the different MSAs and finds that they are positively associated. This corroborates the intuition that housing prices would be higher in certain areas simply because of geography.

According to Saiz's study, among the largest 95 metro areas in the United States (those with population greater than 500,000), MSAs in the Fifth District, such as Charleston-North Charleston, S.C., and Norfolk-Virginia Beach-Newport News, Va.-N.C. are relatively heavily land-constrained. (See table below.) The percentage of undevelopable land is approximately 60 percent in those areas. According to the WRI, regulatory stringency in the two MSAs, however, is relatively low. The impact of LRUs is, in contrast, very large in Baltimore, Md., with a WRI of 1.60.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.