Are Markets Too Concentrated?

Industries are increasingly concentrated in the hands of fewer firms. But is that a bad thing?

In its heyday in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Standard Oil Company and Trust controlled as much as 95 percent of the oil refining business in the United States. Domination of markets by large firms like Standard Oil was emblematic of the so-called Gilded Age, and it sparked an antitrust movement. Ultimately, in 1911 the U.S. Supreme Court would order Standard Oil broken up into more than 30 companies.

Today, many sectors of the economy exhibit similar levels of concentration. Google accounts for more than 90 percent of all search traffic. Between them, Google and Apple produce the operating systems that run on nearly 99 percent of all smartphones. Just four companies — Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile — provide 94 percent of U.S. wireless services. And the five largest banks in America control nearly half of all bank assets in the country.

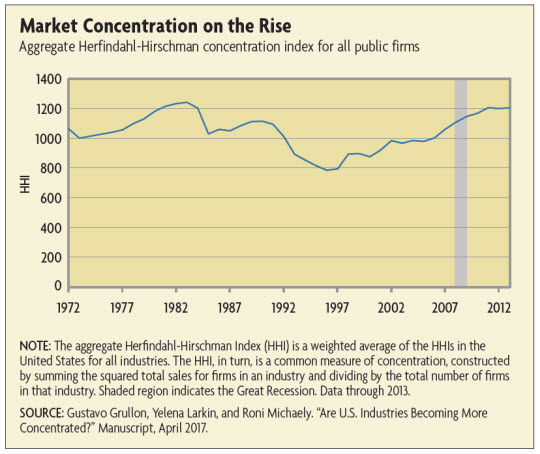

In response to rising concentration in these and other industries (see chart below), commentators and politicians from both sides of the political spectrum have expressed alarm. William Galston and Clara Hendrickson of the Brookings Institution wrote in a January report, "In 1954, the top 60 firms accounted for less than 20 percent of GDP. Now, just the top 20 firms account for more than 20 percent." And a 2017 article in the American Economic Review by David Autor, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; David Dorn of the University of Zurich; and Lawrence Katz of Harvard University reported that concentration increased between 1982 and 2012 in six industries accounting for four-fifths of private sector employment.

"Consumer Payment Choice in the Fifth District: Learning from a Retail Chain," Economic Quarterly, First Quarter 2016.

"Large and Small Sellers: A Theory of Equilibrium Price Dispersion with Sequential Search," Working Paper No. 14-08, March 2014.

"The Financial Crisis, the Collapse of Bank Entry, and Changes in the Size Distribution of Banks," Economic Quarterly, First Quarter 2014.

Several recent studies have attempted to determine whether the current trend of rising concentration is due to the dominance of more efficient firms or a sign of greater market power. The article by Autor, Dorn, Katz, Patterson, and Van Reenen lends support to the Chicago view, finding that the industries that have become more concentrated since the 1980s have also been the most productive. They argue that the economy has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of "superstar firms," which are more efficient than their rivals.

The tech sector in particular may be prone to concentration driven by efficiency. Platforms for search or social media, for example, become more valuable the more people use them. A social network, like a phone network, with only two people on it is much less valuable than one with millions of users. These network effects and scale economies naturally incentivize firms to cultivate the biggest platforms — one-stop shops, with the winning firm taking all, or most, of the market. Some economists worry these features may limit the ability of new firms to contest the market share of incumbents. (See, for example, "Interview: Jean Tirole," Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2017.)

Of course, there are exceptions. Numerous online firms that once seemed unstoppable have since ceded their dominant position to competitors. America Online, eBay, and MySpace have given way to Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Twitter.

"It's easy to say that because there are scale economies in these businesses there can never be competition," says Richard Schmalensee, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has written extensively on the industrial organization of platforms. "But there are scale economies in a lot of businesses. They limit the extent of competition, but they don't wipe it out."

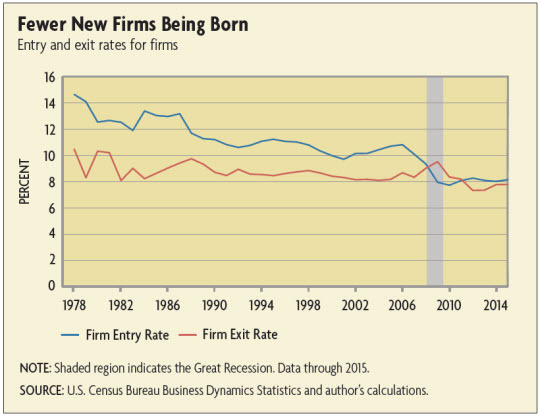

On the other hand, some researchers have argued that this time may be different. Entry rates for new firms have fallen in recent years, perhaps signaling that challengers are finding it increasingly difficult to gain a foothold. (See chart below.) This could be the result of anticompetitive behavior on the part of incumbent firms. Last year, European Union antitrust authorities hit Google with a record-setting 2.42 billion euro fine for allegedly manipulating its search engine results to favor its own services over those of competitors.

Related Listening

In the March 13, 2024 episode of the Speaking of the Economy podcast, Nicholas Trachter shares his research on the market concentration and power of firms.

"One of the potential issues with innovation is that you pay the cost today, but if you can't protect your innovation, then you won't reap the benefits in the future," says Thomas Philippon of New York University. This may be particularly true in industries where initial research and development costs are high but the cost of replication is low, such as in the pharmaceutical industry. The United States and other governments award patents — temporary monopolies — to incentivize firms in such industries to innovate. But it is also possible that firms with strong market power will choose to innovate less, preferring instead to reap the rewards from maintaining high prices on their existing products.

The two theories aren't mutually exclusive. Economists have suggested that the relationship between competition and innovation may follow an inverse U-shaped pattern. At low levels of competition, more competition incentivizes firms to innovate. But if competition levels are already high, innovative firms are more likely to be imitated by competitors, diminishing incentives to innovate. The question is, where do firms in concentrated industries today fall on the curve?

"For most industries in the United States, it looks like we are the side of the curve where more competition leads to more innovation, not less," says Philippon.

Firms' investment levels have been low since the early 2000s relative to their profitability, according to recent work by Philippon and Germán Gutiérrez, his colleague at New York University. After accounting for market conditions, such as lingering scars from the Great Recession, they found that firms in more concentrated industries invested less than those in more competitive markets. They argue this is due to lack of competition.

"When industry leaders are challenged, they actually invest more, both in physical assets as well as intangibles like intellectual property," says Philippon. "I'm sure you can find examples where competition has discouraged innovation, but I think we are far from that today."

No Easy Solutions

Many signs point to rising industry concentration in recent years. What that means for the economy is less clear. Some evidence suggests that rising concentration levels are tied to weakening competition, which is likely to have negative effects on consumer welfare and economic productivity. Other work suggests that efficiency is driving firm consolidation, which is beneficial for consumers. To complicate matters further, both forces could be happening at the same time depending on the industry, making it difficult to disentangle effects in the aggregate economy.

Context also matters for assessing concentration. Two localities can have similar levels of concentration in an industry sector but very different levels of competition. For example, a 2016 study of payment choices in the Fifth District by Richmond Fed economists Zhu Wang and Alexander Wolman found that having fewer banks in a rural setting corresponded with lower card and higher cash usage by customers, suggesting banking services were expensive and not competitive. But they found the opposite in metropolitan areas. Customers of banks in highly concentrated urban markets had higher card adoption. For rural banks, concentration appeared to be a sign of market power, while for metropolitan banks it reflected consolidation driven by efficiency gains.

Still, many have called for more vigorous antitrust enforcement or new laws to address the rise in industry concentration. Carl Bogus, a professor of law at Roger Williams University, wrote in a 2015 article that antitrust law prior to the rise of the University of Chicago view was concerned not only with the economic consequences of large firms, but also with the political consequences as well. Bogus argues for using antitrust law to curtail corporate political power, even if doing so may result in some economic inefficiencies.

Others are skeptical that antitrust is the right tool for this job. Carl Shapiro of the University of California, Berkeley, who served in the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice under President Barack Obama, has written that he supports vigorous antitrust enforcement but that other policies, such as campaign finance reform, are better suited to addressing concerns about corporate political power.

More than a century after the passage of the 1890 Sherman Act, which established American federal antitrust law, it remains a challenge for policymakers to balance concerns about large firms wielding too much market power with a desire not to punish companies that have succeeded on their own merits.

"You worry about a firm that has market power, ceases to innovate, and just charges high prices," says Schmalensee. "But competition sometimes has winners, and one of the worst things you can do as a policymaker is pick on the winners."

Readings

Autor, David, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen. "The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23396, May 2017. (Paper available with subscription.)

Benmelech, Efraim, Nittai Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim. "Strong Employers and Weak Employees: How Does Employer Concentration Affect Wages?" National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 24307, February 2018. (Paper available with subscription.)

De Loecker, Jan, and Jan Eeckhout. "The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23687, August 2017. (Paper available with subscription.)

Grullon, Gustavo, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely. "Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated?" Manuscript, August 2017. (Paper available with subscription.)

Gutiérrez, Germán, and Thomas Philippon. "Declining Competition and Investment in the U.S." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23583, July 2017. (Paper available with subscription.)

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Peter J. Klenow. "The Reallocation Myth." Center for Economic Studies Working Paper No. 18-19, April 2018.

Traina, James. "Is Aggregate Market Power Increasing? Production Trends Using Financial Statements." Chicago Booth Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State New Working Paper Series No. 17, February 2018.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.