What Makes Companies Invest?

Decisions about investment at the firm level are important to the path of economic growth

In November 2018, Amazon announced the site of its second headquarters, which it calls HQ2, in Northern Virginia. Amazon stated that over the next 20 years HQ2 would create 25,000 jobs and occupy upward of 8 million square feet of office space in the greater Washington, D.C., region. "It will mean more employment opportunities for our families, not only with Amazon but also with the companies that will grow up around Amazon," Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Chair Phyllis Randall told the Associated Press. "It will boost our economy as Amazon employees and clients spend money in our stores, restaurants and hotels. A rising tide lifts all boats, and we look forward to the whole community benefitting from Amazon's second home in Northern Virginia and the D.C. Metro region."

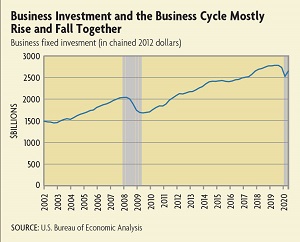

Business investment — like HQ2 — is of prime interest not only to local officials, but also to economists and policymakers concerned with the economic growth of the country as a whole. Over the past few decades, researchers have studied how businesses decide to invest and how those decisions affect the overall economy. In the short term, an increase in investment directly increases gross domestic product (GDP), all else equal. In the long term, investment can influence the economy's growth because investment in capital increases the economy's production capacity, which allows more goods and services to be produced with the same amount of labor. The increases in productivity that come with investment, moreover, are a primary source of improvement in our standard of living.

What, then, shapes the decisions that companies make about investment?

One answer is close at hand: The Fed uses its influence over interest rates in part to influence business investment decisions. Lowering rates decreases the cost for a business to borrow funds to finance investment projects, making a new project easier for the company to justify pursuing; raising rates does the opposite. Interest rates aside, though, there are many factors that influence the investment decisions of firms, including changes in productivity, the business cycle, bank lending, and economic uncertainty. In recent decades, economists have made strides in understanding them.

Investment Isn't Smooth

Business investment refers to something different from financial investment, such as the purchases of stocks and bonds; business investment primarily refers to new capital good purchases. For example, when an airplane company acquires jet engines, it is investing in equipment; when a paper manufacturer builds a new warehouse, it is investing in structures. Strictly speaking, business investment also includes inventory investment, but investments in fixed capital are what mostly interest economists.

Before the 1990s, it was common in economics research to think of a firm's investment behavior as mostly smooth and reflective of an investment demand curve in which investment is driven by changes in interest rates. As it turns out, however, investment behavior at the firm level is often characterized by periods of low or zero investment followed by large discrete changes, commonly referred to as investment spikes. Such feast-or-famine investment behavior can be called "spiky" or "lumpy" investment. Many spikes in the investments of small firms can add up, in turn, to significant changes in aggregate investment. Recently, economists have started to pay more attention to the macroeconomic effects of firm investment spikes, and policymakers have discussed the importance of investment spikes in considering policies to stimulate investment when it would otherwise be declining during recessions.

Two of the first economists to study plant-level investment were Mark Doms, the chief economist at the Congressional Budget Office, and Timothy Dunne, a professor at the University of Notre Dame. In a 1998 article in the Review of Economic Dynamics, Doms and Dunne observed that relying solely on national-level statistics — as many economists had done up to that point — would not explain the complex dynamics of different industries or operations of a typical plant. To account for these differences, they used data from the U.S. Census Bureau's Longitudinal Research Database and the Annual Survey of Manufactures. Analysis of these data led them to discover three things. First, many plants do not alter their capital stocks smoothly. Most plants alter their net capital stock by less than 10 percent every year, on average, but at some plants that pattern is punctuated by major investment increases. Second, those major increases are concentrated most often in smaller plants, plants that undergo a change in organizational structure, and plants that switch industries. Third, large investment projects in a small number of plants and changes in the number of plants undergoing investment episodes greatly affect aggregate investment.

The concept of investment spikes was explored in 2007 by economists Francois Gourio of the Chicago Fed and Anil Kashyap of the University of Chicago. In an article in the Journal of Monetary Economics, they showed the effects of plant-level investment spikes on aggregate investment using data from manufacturing plants in the United States and Chile. They defined plant-level investment spikes as periods in which the ratio of investment to capital stock was greater than 20 percent. The investment ratio describes the relationship between the amount of money invested and the value of a plant's existing capital stock.

They argued that one reason many firms choose not to adjust their capital smoothly is because investment has high fixed costs. "If a firm wants to do a big investment project, they may need to shut down the assembly line for a while," Gourio explains. "So sometimes it is better [for firms] to do everything at once rather than spread it out over many years." Gourio and Kashyap showed that for both U.S. and Chilean plants, the majority of the variation in national investment was caused by plants undergoing investment spikes. Upon further analysis, they concluded that changes in the number of firms making large investments had a greater effect on the variation in the aggregate investment ratio than changes in the average size of the investment spike per plant. Additionally, the prevalence of investment spikes in one year predicted future aggregate investment. Years with relatively more investment spikes were followed by years with relatively less investment.

The high fixed costs of investment prevent a firm from immediately reaping the rewards of its investment project. In a Business Review article, Aubhik Khan of Ohio State University wrote, "Because it takes time to manufacture, deliver, and install new capital goods, investment expenditures today do not immediately raise the level of a plant's capital." Thus, he explained, firms will tend to increase their investments only "in response to forecasted changes in the market's demand."

Productivity Shocks

Productivity also makes a difference for a firm's investment decisions. If productivity increases — that is, if the firm becomes able to create a larger quantity of outputs with the same level of inputs — then investment will likely increase. For example, a firm's productivity can increase if it finds ways to lower manufacturing costs. By lowering production costs, the firm can reap a higher profit per unit or sell more of its products at a lower price. Following this, the firm can expand and hire more workers, and investment will rise.

"How Do Small Business Finance and Monetary Policy Interact?" Economic Brief No. 20-11, October 2020

"Misallocation and Financial Frictions: The Role of Long-Term Financing," Working Paper No. 19-01R, January 2019 (revised August 2020)

The relationship between productivity and investment flows in both directions, however. A study recently published in the Journal of Business & Economic Statistics by Michał Gradzewicz of the National Bank of Poland investigated the relationship between investment spikes and productivity at the firm level. He used the financial reports and balance sheets of Polish firms to model the economic effects of investment spikes and how they relate to firm-level total factor productivity (TFP), the ratio of output to inputs. TFP is often used as a measure of productivity or economic efficiency because it explains the portion of growth in output that cannot be explained by growth in inputs of labor and capital. His model predicted that a firm's TFP would increase before an investment spike, fall immediately afterward, and then slowly recover. One reason for the drop in TFP is that firms need time to adjust their operations and train their employees on how to use new capital following investment. During this time, firms become less productive because they are gaining experience with the new equipment — their employees are learning by doing. On average, it took four years for TFP to surpass its initial level following an investment spike. For smaller firms, the fall of TFP was more pronounced and it took even longer to recover.

In another study, Thomas Winberry of the University of Chicago examined how aggregate investment responds to investment at the firm level and how aggregate and firm-level investment responds to productivity shocks and stimulus policy. Using IRS tax data, he constructed a model that matched both the volatility of firm-level investment and the real interest rate dynamics of national data. His model accounted for the procyclical volatility of investment, so it better matched the national response to changes in productivity. He concluded that when many firms are close to their adjustment threshold for investment, an additional productivity shock induces a large spike in aggregate investment; on the other hand, when only a few firms are considering investing, an additional shock makes less of a difference to aggregate investment.

Business Cycles

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.