Insert Coins

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the supply of many items, including cold hard cash

"The Decline in Currency Use at a National Retail Chain," Economic Quarterly, Second Quarter 2018

"Consumer Payment Choice in the Fifth District: Learning from a Retail Chain," Economic Quarterly, First Quarter 2016

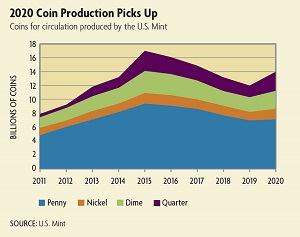

Officials for the Fed and the U.S. Mint, which produces new coins for circulation, were quick to assure the public that the United States did not have a coin shortage, per se. There was roughly $48 billion worth of coins in circulation, and the coronavirus did not cause that change to vanish. What it did do was dramatically slow the circulation of those coins through the economy.

Less than 20 percent of the coins that circulate through the economy each year are newly minted stock. The rest are older coins that are recirculated through the regular flow of commerce. The Fed distributes coins to depository institutions according to demand, and those institutions in turn supply coins to businesses and consumers. The supply of coins at banks and the Fed are replenished when businesses or households with excess coins deposit them at a bank or a coin aggregator kiosk like those operated by Coinstar, and the whole process starts over again. The average lifespan of a coin is 30 years, so change can be reused in this way many times before it is replaced.

The pandemic shook up economic activity in ways that disrupted the normal flow of coins. Some banks initially closed their lobbies and shifted business to drive-thru windows and online, making it difficult for businesses and individuals who might ordinarily bring change in for deposit to do so. And even where the option to deposit coins was still available, business owners and consumers sometimes chose to avoid the activity to limit potential contact with the virus.

Consumers also changed their payment habits in response to the pandemic. A Fed survey of consumer payment choice released in July reported that 22 percent of respondents had switched from making in-person payments to paying online or over the phone, and 28 percent of respondents were specifically avoiding paying in cash, using a debit or credit card instead. This may have stemmed from concerns that cash could be a transmission vehicle for the virus. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that people avoid touching their face and wash their hands after handling cash to minimize the risk of infection. A survey by the Bank of Canada found similar behavioral changes among Canadians: 35 percent reported decreasing their use of cash, and 17 percent said they were taking extra precautions when handling cash, such as washing their hands after making a purchase.

For years, some economists and lawmakers have called for eliminating the penny because it has long been costlier to produce than it is worth at face value.

But for the millions of households that still rely on cash as their only payment method, the coin disruption has been more impactful. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's 2019 Survey of Household Use of Banking and Financial Services, 5.4 percent of U.S. households (that is, about 7.1 million of them) are unbanked, meaning they do not have an account at a bank or credit union. Additionally, the Fed estimates that another 16 percent of American households are underbanked, which means they have a bank account but still regularly rely on financial services outside of the traditional banking sector, such as check cashing and payday loans.

Low-income households are much more likely to be unbanked and reliant on cash. Zhu Wang and Alexander Wolman of the Richmond Fed studied a dataset of 2 billion transactions between 2010 and 2013 at a nationwide discount retailer with thousands of stores across the United States. In a 2016 paper in the Journal of Monetary Economics, they reported that income and access to competitive banking options strongly influenced how often consumers chose cash. The stores in their sample were largely located in low-income ZIP codes, and most transactions consisted of small-dollar purchases. Consequently, even though cash use followed the national downward trend over the three years in their study, it remained the dominant payment method, accounting for between 75 to 85 percent of all transactions. In a follow-up study, published in the Richmond Fed's Economic Quarterly in 2018, they showed that this retailer's average cash share of transactions across ZIP codes remained at 70 percent by 2015.

"We found that cash is more likely to be used by consumers in neighborhoods with lower income, less banking competition, or smaller population density because consumers in those locations may not have easy access to electronic payments, or they face higher costs for using them," says Wang. "The coin disruption would presumably have more of a negative impact on consumers in those neighborhoods."

Before the current crisis, some retailers experimented with going cashless. Online giant Amazon opened several physical stores with no registers or cashiers. Customers would instead scan an app connected to their Amazon account when they entered and exited the store to pay for any items they bought. Concerned that such a trend would harm unbanked households, several states responded by passing laws requiring all stores to accept cash.

In a 2019 working paper, Atlanta Fed economist Oz Shy attempted to estimate the cost to consumers if all stores were to go completely cashless. Unsurprisingly, he found that the cost would be quite small for consumers who have debit and credit cards but use cash from time to time by choice. But for households who don't have access to debit or credit cards, Shy estimated a drop in their consumer surplus of nearly 31 percent per transaction.

Without cash and coins in circulation, it's harder for underbanked families to buy basic necessities and to fully participate in the economy," says Walker of FMI.

Getting Coins Moving

Officials at the Fed and the Mint are determined to get coins circulating again for the businesses and households that rely on cash every day. In July, the Fed convened a U.S. Coin Task Force in partnership with the Mint and other participants in the coin supply chain, such as retailers, armored carriers, and coin aggregators.

The Task Force declared October to be "Get Coin Moving Month," encouraging households to check their couches, cupholders, and coin jars for loose change and safely deposit it at banks or coin kiosks. Banks and retailers were also encouraged to run promotions for customers bringing in coins or paying in exact change. Since the Task Force was formed, many businesses and households have taken the opportunity to turn their change into cash while helping to recirculate coins into the economy. One aquarium in North Carolina shuttered by the pandemic put its employees to work hauling 100 gallons of coins from one of its water fixtures that had served as a wishing well for visitors since 2006. Overall, efforts like these have started to yield results.

"We are in a different place than we were in March and April," Melissa Murdock, vice president of communications and media relations for the Retail Industry Leaders Association, said in an email. "I haven't heard from my members about this in months."

But others have seen more modest improvements so far. Wallace said that in a recent survey he conducted of laundromat owners, less than 20 percent reported that coin flow and availability of coins at banks had improved. Walker heard similar things from grocery store owners.

"While coin circulation is improving, our members are still experiencing lingering challenges in getting a full coin supply into their stores," she said.

The Coin Task Force expects circulation will gradually return to normal as more parts of the economy reopen. But will demand for cash and coins return to its previous level? The pandemic seems to be accelerating some changes in the behavior of businesses and consumers, such as the widespread adoption of teleworking and e-commerce. Will payment habits be similarly affected?

"A long-term trend we have seen in the data is the continuous migration from paper payments to electronic payments," says Wang. "This has been driven by a couple of factors, including the income growth of consumers, technological progress in electronic payment means, and the increasing popularity of online shopping. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to add a further push to this migration."

In his survey of laundromat owners, Wallace was somewhat surprised to learn that 40 percent of respondents were looking into alternative payment systems such as card readers as a result of current disruption.

"Now, I'm not sure how many of them will actually go out and buy a new payment system," he said. "These are small mom and pop businesses for the most part, so the decision to add a new payment option is a capital investment they need to weigh against the benefits. But I think it's natural that business owners are thinking of ways to reduce their vulnerability to something like this should it happen again."

Readings

Chen, Heng, Walter Engert, Kim P. Huynh, Gradon Nicholls, Mitchell Nicholson, and Julia Zhu. "Cash and COVID-19: The Impact of the Pandemic on the Demand for and Use of Cash." Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper No. 2020-6, July 2020.

Kim, Laura, Raynil Kumar, and Shaun O'Brien. "Consumer Payments and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Supplement to the 2020 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice." Cash Product Office of the Federal Reserve System, July 2020.

Shy, Oz. "Cashless Stores and Cash Users." Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper No. 2019-11a, May 2019 (revised August 2019).

Wang, Zhu, and Alexander L. Wolman. "Payment Choice and Currency Use: Insights from Two Billion Retail Transactions." Journal of Monetary Economics, December 2016, vol. 84, pp. 94-115.

Wang, Zhu, and Alexander L. Wolman. "The Decline in Currency Use at a National Retail Chain." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Second Quarter 2018, vol. 104, no. 2, pp. 53-77.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.