Perspectives on the Banking Turmoil of 2023

The banking turmoil of March 2023 was a significant incident in the U.S. financial system that threatened to create a general macroeconomic problem. There were multiple factors at play that explain what happened. In this article, I discuss some of those factors in detail to gain a more complete understanding of why and how the turmoil happened and the way policy addressed it.

During the first two weeks of March 2023, several medium-to-large U.S. banks experienced significant stress, and two of these banks — Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank — were taken over by regulators and closed. As is generally the case, multiple factors combined to create the conditions propitious for these events. The crisis resulted in a massive shift in the way funds flow from depositors to banks and other investment alternatives. The Federal Reserve played a critical role in containing the impact of the crisis and redirecting some of the funding to where it was urgently needed. Incentives, market discipline and fear of contagion are important considerations behind the decisions taken during the crisis and the implications of the events for the future performance of the U.S. financial system. In this article, I provide some detailed perspectives on these various issues with a view to improving understanding of the forces driving the events and the way policy responded.1

The Early Gestation of the Crisis

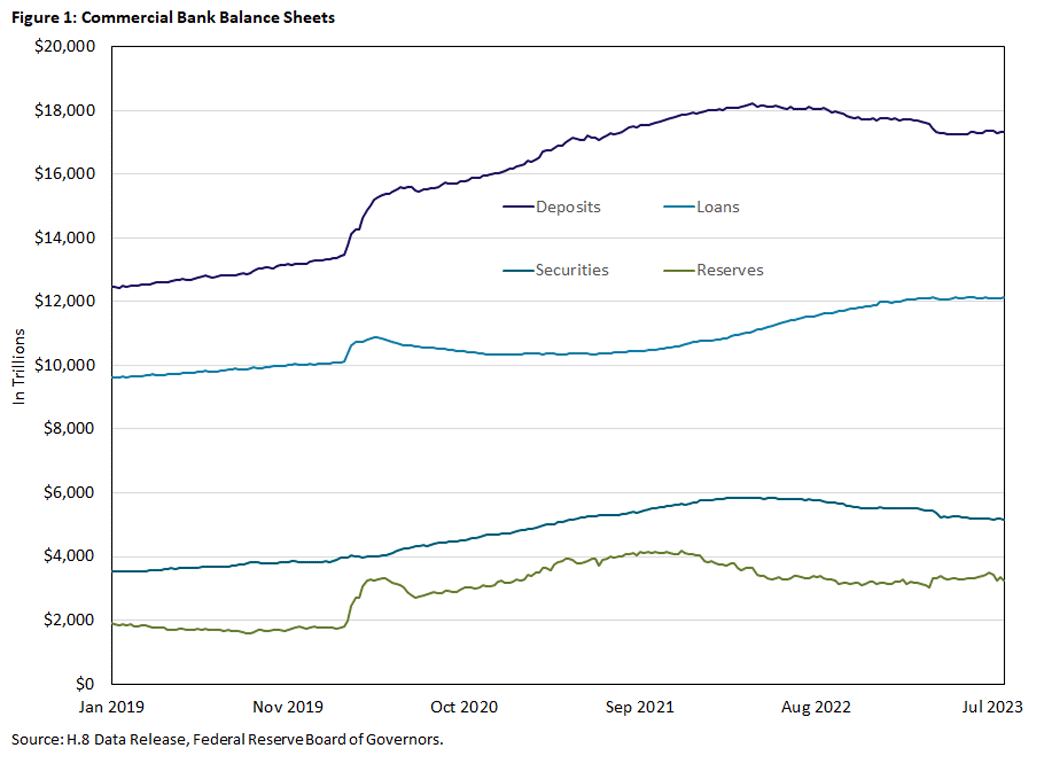

Many of the conditions behind the recent stress in the U.S. banking system originated a few years prior. To begin, bank deposits increased considerably during the pandemic, as shown in Figure 1. After an initial surge — which had as counterpart a surge in both business lending (via lines of credit drawdowns) and bank reserves — deposits continued growing rapidly for more than a year. As banks were receiving these extra deposits, the economy continued to struggle through the pandemic, with limited demand for new bank loans. Much of the increase in deposits, then, ultimately went to increase banks' reserves and, importantly, holdings of long-term securities.

At the time, expectations for the level of interest rates were very low, even for horizons of two to three years out. The U.S. economy was coming from an extended period of persistently low interest rates and inflation rates, and expectations for future inflation were notably subdued. The U.S. government was issuing large amounts of debt, the result of a huge fiscal effort intended to support businesses and households coping with the pandemic. The housing sector was very active, and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issuance was consequently quite high. Banks absorbed considerable amounts of MBS.

Treasuries and agency securities (debt and agency-guarantee MBS) have little-to-no credit (or default) risk. However, interest-rate risk can, in principle, be significant for securities with longer maturities. The expectation of persistently low interest rates and inflation made that risk less prominent at the time. And given the prospects for low future rates, securities with fairly long maturity were issued with very low coupon payments. It was a good time to issue long-term debt, and it also seemed relatively safe for banks to hold that debt as a way to allocate deposit funding that was widely available but not much needed for lending to businesses and households.

The Onset of Higher Inflation and Interest Rates

Around the second quarter of 2021, however, signs of inflation in the economy appeared more and more evident. Initially, it was hard to disentangle how much of that inflation was associated with the disruptions in supply and demand caused by the pandemic and also whether those inflation pressures would dissipate by themselves as health risks became more manageable and the economy returned to normal.

Later in 2021, however, it became clear that interest rates needed to increase and that the Fed would embark in a process of monetary policy tightening. The first rate hike occurred in March 2022, and the speed at which policy rates increased during 2022 was unprecedented.

These higher interest rates meant the securities purchased during the pandemic (at very low coupon payments) were no longer a great investment. Initially, banks' balance sheets and earnings did not show the impact of the repricing, as deposit interest rates often take time to adjust to changes in policy interest rates. This is particularly true when rates move fast, as they did in 2022.2 So, while interest payments from the banks' holdings of securities were low relative to the prevailing policy rate, the deposits funding those holdings were also paying relatively low interest rates. That is, low-interest securities were being financed with low-interest deposits.

If inflation were to prove temporary, perhaps policy rates could increase less and maybe even go back down soon enough. If that would have happened, losses for banks holding low-interest securities would have been less substantial: Deposit rates would have come back down, and the funding-cost mismatch would have lasted for only a few months. However, inflation persisted, and the policy rate continued to increase briskly during 2022. During the second half of the year, depositors reallocated large amounts of funds into higher-yielding investments. As bankers recognized this, deposits began to reprice.

The Height of the Crisis

With 2023 underway, more and more depositors realized there were very attractive interest rates available for investing cash in the market. Flows into, for example, prime money market mutual funds (MMFs) increased quickly, and bank deposit growth effectively stalled.

In early March, depositors at several mid-size banks — including SVB and Signature Bank — became concerned that deposits repricing at permanently higher interest rates would cause bank profitability to suffer, putting some of these banks in trouble.3 The large proportion of uninsured deposits at some of the banks was also a source of fragility.4 In fact, a few regional banks had multiple sources of weakness, and depositors fled from these weaker banks first, as is often the case during banking crises.5

As stress at regional banks got in the news, awareness among depositors increased, and repricing of deposit terms became more widespread. Earning prospects for banks holding significant bond portfolios looked a lot worse: Bonds were paying around 3 percent, and the cost of funding with deposits was anticipated to go up to 4 or 5 percent.

In this context, it is not surprising that banks' stock prices suffered. Arguably, the large drops in bank stock prices created even more awareness and concern among depositors. In many cases, deteriorating confidence in the financial condition of their banks drove depositors (both insured and uninsured) to move their cash holdings to other (larger) banks or outside the banking system.

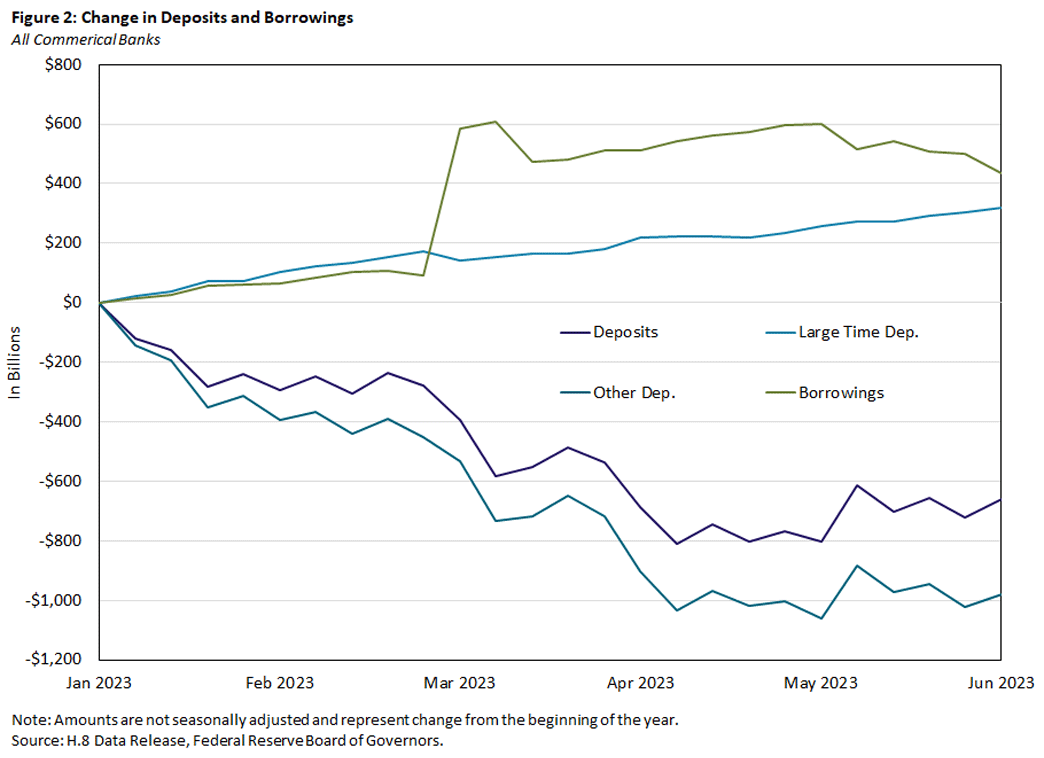

Figure 2 shows the evolution of deposits and borrowings for all U.S. commercial banks in the first half of 2023. Borrowings include collateralized loans from Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) as well as borrowings from the Fed.

As is clear from the figure, both borrowings and large time deposits increased consistently, with borrowings jumping abruptly during the first two weeks of March. Total deposits — driven mainly by other deposits, which include core deposits such as checking and savings accounts, a more stable source of funding for banks — decreased consistently until the end of April and then stabilized at a significantly lower level.

However, Figure 2 hides important differences in deposit flows across the size distribution of banks: The publicly available data only separates the top 25 largest domestic banks from the rest. As a result, visibility of this issue is limited. In May, economists at the New York Fed with access to more granular (confidential) data confirmed that there were significant flows of deposits in March 2023 from banks with assets between $50 billion and $250 billion (which the authors call super-regional and which included both SVB and Signature) to banks with more than $250 billion in assets.

The Shift in Bank Funding Sources

While large banks (those with assets over $250 billion) initially saw significant increases in deposits, those inflows had reverted to much lower values by the end of March 2023. Borrowing increased for banks of all sizes.

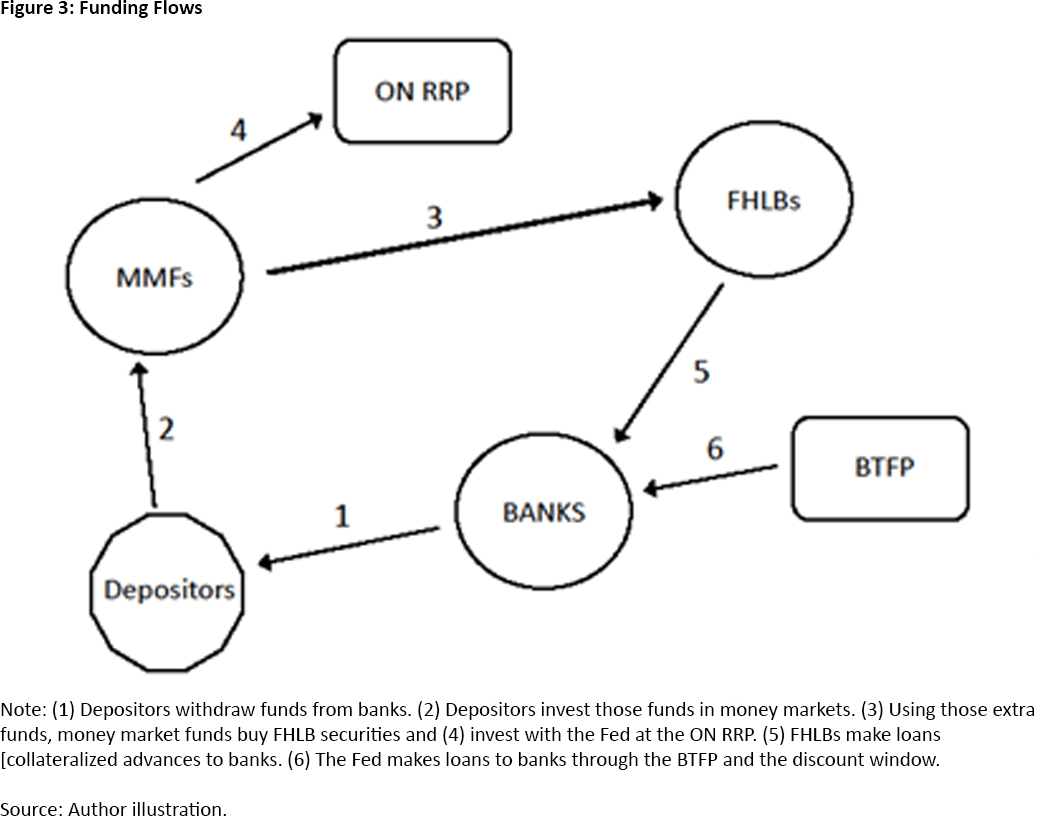

Figure 3 illustrates one aspect of the flow of funding to banks that resulted from this shift — in particular, the FHLB channel. We can think of this process as a partial rerouting of the existing bank funding. The funding that was going directly from depositors to banks before March became intermediated by MMFs and FHLBs after the turmoil.

There are two important implications of this rerouting of funds:

- Not all MMF funding goes to FHLBs to then lend to banks. MMFs also deposit with the Fed in the overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) and buy bonds directly in the market.

- FHLB funding to banks tend to reprice much faster than core deposits. So, this rerouting implied that the sensitivity of bank funding to interest rate movements increased considerably.6

Collateral Funding and the Fed's Response

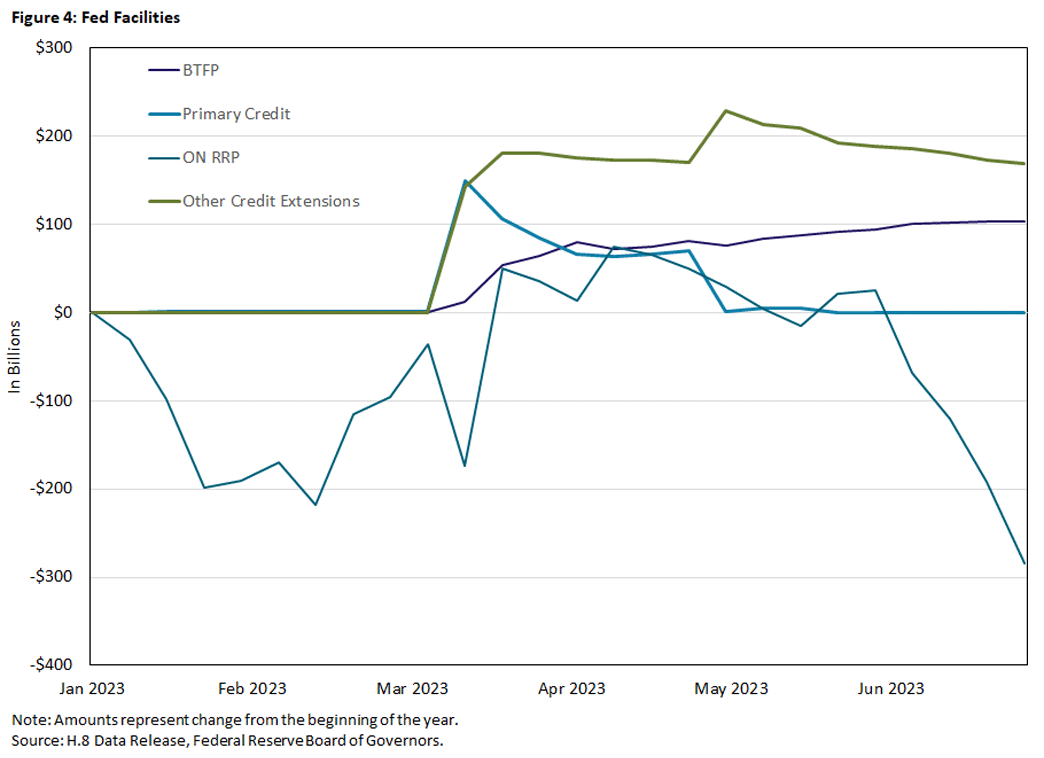

In an effort to contain the crisis, the Fed also created the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) during the second week of March. The program offered advances (collateralized loans) to banks with terms of one year or less at a market rate consistent with the expected path of interest rates in the year ahead from the day of origination (plus a premium of 10 basis points). The collateral was restricted to Treasury and agency securities (including MBS) valued at par and owned by the borrower when the program began. Note that these are the same categories of securities that banks had accumulated during the pandemic, as deposits surged.

One way to think about this new Fed-provided funding, then, is as a replacement of the funding by depositors prior to the banking stress. In summary, depositors' funding decreased and was replaced by funding from the FHLBs and the Fed. These sources of funding are, in principle, more tightly linked to the level of market interest rates and in that way diluted the advantage that banks were perceived to have as interest rates changed and core deposits were slow to reprice.

As Figure 4 shows, the primary credit facility at the Fed's discount window also saw an increase in activity during the height of the crisis, but that lending quickly normalized in the following weeks. The discount window only provides loans with a maximum maturity of 90 days. Also, while the collateral taken for those loans is broader (including business and consumer loans), haircuts are applied to the securities pledged at the discount window, making it less attractive to fund Treasury and MBS, with the no-haircuts BTFP as a better alternative. A notable pattern in Figure 4 is displayed by "Other Credit Extensions," which includes the loans that the Fed made to those banks that were eventually closed amidst the turmoil.

Interestingly, FHLB advances are also collateralized loans with more restricted collateral classes than the discount window but comparable to the collateral at the BTFP. In that way, FHLB and BTFP advances are closer substitutes. An important limitation for the BTFP, however, is that the collateral pledged for those advances had to be securities that the borrowing bank owned prior to March 12, 2023. In other words, BTFP funding could not be used by banks to purchase new securities after March. There are, of course, also differences in the way FHLB and BTFP advances are being priced, but conditional on term of maturity, those differences in interest rates are not likely to be significant.

On the other side of the same coin, then, from the perspective of collateral funding, we can think that a large portion of Treasuries and agency securities held by banks before March 2023 were being financed with deposits. After the March stress, however, funding for bank holdings of Treasuries and agency securities shifted, and banks instead funded a significant share of their eligible securities with FHLB and BTFP advances.

Policy and the Fear of Contagion

Both Signature and SVB were medium-to-large banking organizations. SVB grew rapidly during the pandemic, becoming the 16th largest bank in the U.S. by December 2022, while Signature ranked 29th. Both banks suffered a rapid loss of depositors' confidence in early March 2023. Abnormally high concentrations of uninsured deposits likely contributed to the massive shift in sentiment among depositors of these banks. At year-end 2022, over 90 percent of the deposits at these banks were uninsured. Other items influencing the sudden nature of the panic included the banks' customer concentration in particular industries as well as technological improvements allowing both increased communication among depositors and increased speed at which fund withdrawals could happen.

Bank instability has received a lot of attention in the financial economics literature. Indeed, the 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes work on this issue. This literature has made significant progress in understanding how rational behavior by uninsured depositors can result in panics triggering a wave of fund withdrawals from a bank, possibly generating inefficient liquidation of productive investment. These panics can be caused by factors that coordinate the change in mood of depositors even without constituting a significant reassessment of the financial conditions of the bank, aside from the obviously consequential loss of confidence by depositors itself.

When conditions are suited for bank fragility, instability in one bank may trigger a loss of confidence in another bank. This kind of contagion is a looming threat for bankers and policymakers trying to contain a crisis. It is reasonable to think that a problem in only one or two banks can be addressed by reallocating assets (and liabilities, in principle) to other banks, other financial institutions or large investors on the sidelines. However, if the crisis spreads to many banks through contagion, the situation can become unmanageable and have a significant impact on the aggregate economy. With these concerns in mind, government interventions during crises are often designed to be clear and assertive — "decisive actions" signaling unambiguous support to the financial system — and thus intended to suppress the possibility of mood-driven contagion. In March 2023, the decision was made to fully protect all depositors, insured and uninsured, in SVB and Signature.

These actions were taken in application of a systemic risk exception. The U.S. deposit insurance system contemplates insuring depositors up to a maximum of $250,000. Part of the philosophy behind this limit is the presumption that large depositors tend to be more sophisticated and can exercise helpful market discipline on bank managers over the way they run their bank.7 When the limit on deposit insurance is lifted ex post, that undermines the incentives of large depositors to oversee bank activities in the future. Presumably, optimal bank regulation should adapt and reflect this new situation accordingly. Regulators need to fill the gap left by inattentive depositors.

Similarly, larger banks in the U.S. (those with more than $250 billion in assets) are subject to stricter supervision and regulation in part due to the systemic concerns that financial trouble in those banks can bring to the system as a whole. When smaller banks are treated as "systemic," regulation also needs to adapt to this new situation. What constitutes a systemic event is not clear-cut and can change over time. We might have learned in March 2023 that some banks are more systemic than previously thought. If this is the case, then it makes sense for the bank regulatory framework to reflect this improved understanding going forward.8

It is also possible, however, that some of the ex-post response to the crisis reflects time inconsistency: The policies that were deemed ex ante optimal — in part to influence prudent behavior by economic agents, preemptive of crises — are no longer desirable ex post in the midst of the crisis. Finding ways to address the well-understood perils of such limited policy commitment is important.

At the same time, since regulation is costly, pressures to deregulate take a cyclical pattern, and they always come back. It seems unlikely that the answer to each new crisis is more and more regulation. Market discipline should play a role. Consequently, it remains an important assignment to try to design regulation in ways that make it more amenable (during a crisis) to maintaining commitment over the level of investor protection decided ex ante.

Conclusion

A lot of factors influenced the banking turmoil of 2023. This article provides perspectives on some of those factors without attempting to be exhaustive. Each of the banks that experienced stress had very specific situations that contributed to their problems. We have taken a step back from those details and have outlined some broader issues that also played a role on the way events unfolded. The hope is that these perspectives help in thinking about the various fundamental reasons behind banking crises to, then, be able to address those more accurately and effectively in the future.

Huberto M. Ennis is group vice president for macro, micro and financial economics in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

For additional perspective, see the recent remarks by Richmond Fed Research Director Kartik Athreya.

It seems unsurprising that deposits took some time to reprice. After experiencing a very long period of interest rates near zero, the fast pace of policy-rate tightening left many depositors with underpriced deposits and either not realizing or not having a good plan for how to reallocate money into higher-yielding investments.

A thorough account of the multiple weaknesses at SVB, for example, appears in the April 2023 review led by Federal Reserve Board Vice Chair Michael Barr.

On March 8, Silvergate Bank (a smaller institution providing services to cryptocurrency investors) was also closed and liquidated, adding to the sense of instability in the banking sector at the time.

For more on how bank runs tend to affect weaker banks more intensely, see the 1997 paper "Contagion and Bank Failures During the Great Depression: The June 1932 Chicago Banking Panic."

This was also a period of significant cross currents in the bond market, where MMFs are a critical group of investors. As a result of federal debt-ceiling tensions, the Treasury Department adjusted its issuance of debt and the amount of cash held in its Treasury General Account at the Fed. MMFs also shifted to invest heavily in shorter tenors given the uncertainty surrounding monetary policy. Furthermore, the Fed was reducing the size of its balance sheet (and continues to do so as of this writing), which implies that the private market needs to absorb an increasing portion of the outstanding government securities. The net impact of these various factors on the observed outcomes in the banking system is not easy to disentangle and is left aside for the purpose of this discussion.

Fed Vice Chair Barr's review clearly highlighted managerial failure as one deficiency in the case of SVB.

Discussions for reforming the current U.S. bank capital and regulatory framework are already underway. See also the recent speech by Fed Governor Michelle Bowman.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Ennis, Huberto M. (October 2023) "Perspectives on the Banking Turmoil of 2023." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 23-35.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.