Brush Up Those Resumes, Dust Off That Disco Ball?

With today's combination of high inflation, high gas prices, supply constraints and geopolitical tensions with Russia, some observers have commented on parallels between the present moment and the 1970s. We might have another item to add to the list: labor market tightness.

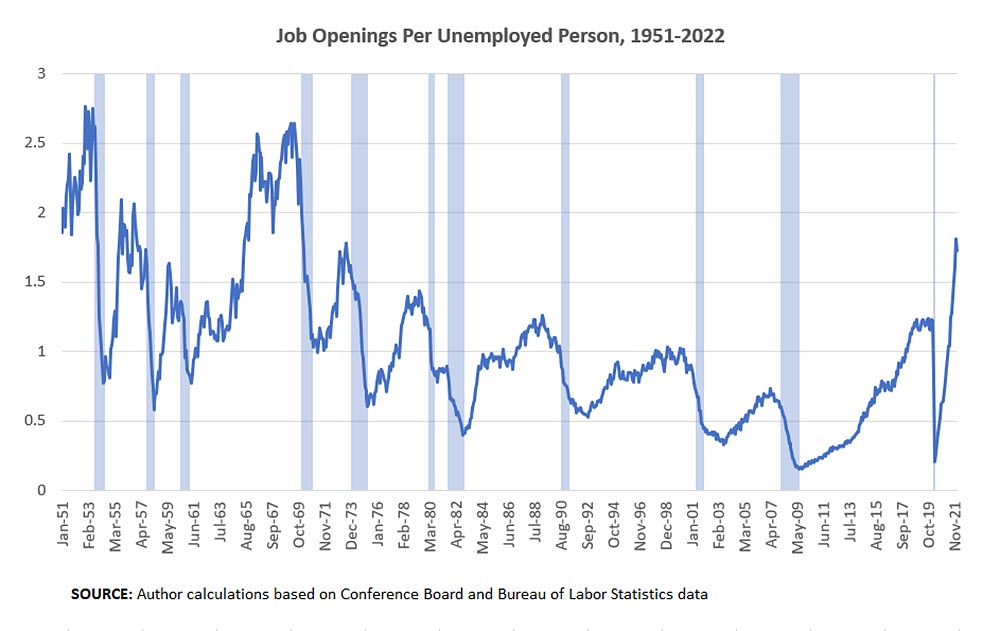

While the unemployment rate has yet to fall to its pre-pandemic level, another measure of labor market tightness has reached levels not seen since the 1970s: job openings per unemployed person. Indeed, in the press conference following the March FOMC meeting, Chair Powell characterized January's ratio of 1.7 as "a very, very tight labor market, tight to an unhealthy level." Does this mean there's a risk of 1970s-style inflation?

Figure 1 below shows the history of job openings per unemployed person dating back to 1951. Prior to the pandemic, the last time we observed a value of 1.7 was August 1973.

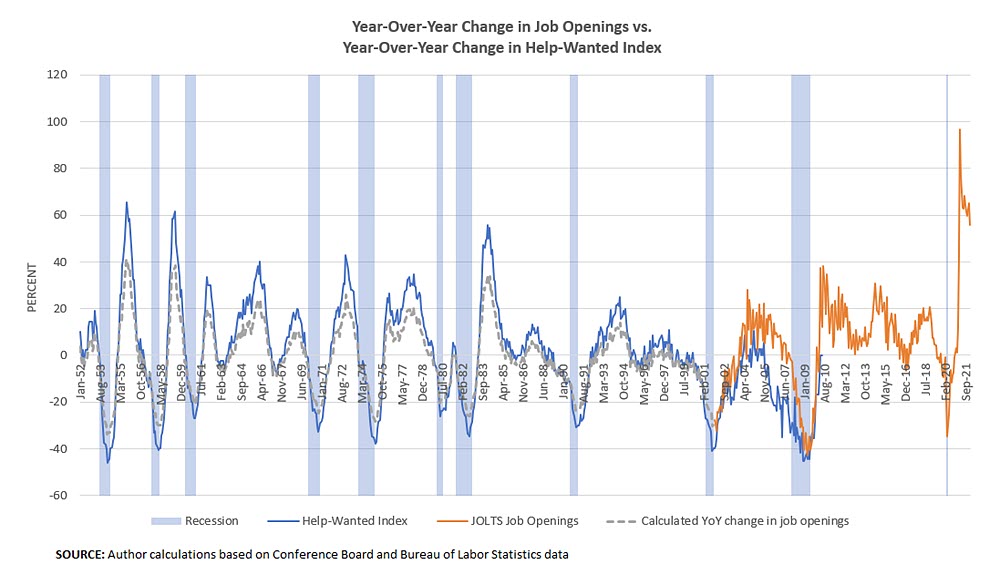

Technically, the Bureau of Labor Statistics' data from its Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) only start in 2000 — so how did we calculate the longer history? We benchmarked historical job opening levels to the Conference Board's now-discontinued Help-Wanted Advertising Index (HWI). This series has a long history of being used to construct historical job openings. For example, Richmond Fed economist Thomas Lubik has used the series to study job search by already-employed workers, a topic that seems particularly timely given today's elevated quit rate and labor market churn. Regis Barnichon at the San Francisco Fed created a composite Help-Wanted Index that combines the Conference Board's discontinued HWI with an updated online help-wanted series, documenting the HWI's close link to JOLTS in the process.

As shown in Figure 2 below, over a roughly 10-year period starting in 2001, year-over-year percent changes in the composite HWI tracked closely with year-over-year changes in BLS job postings. We extended the statistical relationship between these two series into the past to construct historical year-over-year growth rates and then backed out the implied job opening levels.

Based on job openings per unemployed person, labor markets are as tight as they were in the '70s, a time when rising wages worked in concert with rising prices to keep inflation elevated for years. While the similarities are disconcerting, thankfully this time is different: Current data on wages and inflation don't yet suggest that a 1970s-style wage-price spiral is developing today. Most important, the Fed now has an explicit 2 percent inflation target that has kept long-run inflation expectations anchored.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.