Rural Populations Face Higher and More Volatile Unemployment Rates

With almost one-quarter of the Fifth District1 population located in small towns and rural areas, the Richmond Fed is committed to shedding light on the challenges and economic conditions faced by such communities. Limited data availability (due to the cost of fielding surveys) can be a hindrance to understanding real-time economic conditions in rural communities. For example, the Consumer Price Index focuses on prices paid by urban consumers, while the Current Population Survey (CPS) — the underlying survey behind national unemployment rate data — does not have a large enough sample to allow for proper estimates to be obtained at the county level. Nevertheless, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has developed methods of estimating county-level labor market indicators. In this week's post, I use these estimates to study trends in rural and urban unemployment rates in the Fifth District.

The underlying data for the rural and urban unemployment rates described in this post come from the BLS's Local Area Unemployment Statistics program, which provide monthly estimates of county-level employment and unemployment levels. While estimates of these series for the District of Columbia are derived from the CPS, county-level estimates must be calculated using alternative data sources including the Current Employment Statistics Survey, the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, unemployment insurance claims counts, and the American Community Survey. The BLS uses these alternative data to estimate the share of state-level unemployment and employment represented by a particular county in each month. These shares are then multiplied by the state-level estimates of these series to produce county-level estimates. The county-level labor force is the sum of county-level employment and unemployment.2

I classify each county as either rural or urban using the same approach as the Richmond Fed's Rural-Urban Comparison Maps: Counties with a score of 1 or 2 according to the USDA's Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs) are classified as urban, while counties with RUCCs of 3-9 are considered rural. For each geography (that is, state, territory, or the full Fifth District), I calculate the rural unemployment rate as the ratio of the rural unemployed population to the rural labor force.3

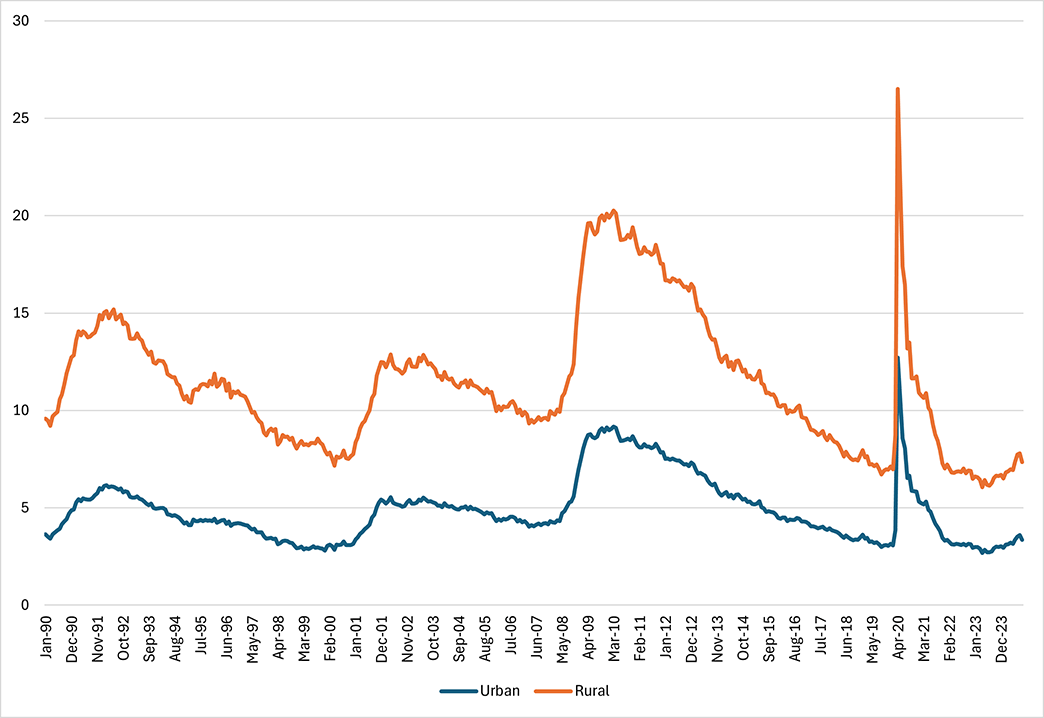

Estimates of the rural and urban unemployment rates in the Fifth District are plotted in Figure 1 below. The figure shows that the Fifth District's rural residents face consistently higher unemployment rates than its urban residents.

Table 1 below shows that this is true at the state level as well as for the Fifth District as a whole. Table 1 also suggests that changes in rural unemployment rates over the past year have been similar to changes in urban unemployment rates, which is partly due to the way these estimates are constructed (as shares of the overall state-level data).

Direct surveys of rural household employment could potentially show sharper differences in unemployment between rural and urban areas. Nevertheless, these estimates do suggest that rural labor markets have weakened in the Fifth District over the past year, with especially sharp deterioration in rural South Carolina, where the unemployment rate is 2 percentage points higher versus a year ago.

| Rural | Urban | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography | Current | 12m Ago | Difference | Current | 12m Ago | Difference |

| DC | 5.5 | 5.0 | 0.5 | |||

| MD | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| NC | 3.8 | 3.8 | -0.1 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 0.0 |

| SC | 5.4 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| VA | 3.2 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.0 |

| WV | 4.6 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 0.2 |

| 5th District | 4.0 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 0.4 |

| Source: Author's calculations using Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Labor Statistics data via Haver Analytics | ||||||

In addition to being higher than their urban counterparts, rural unemployment rates also appear to be more volatile. Table 2 shows the standard deviation of unemployment rates for Fifth District geographies from January 1990 to September 2024. Rural unemployment rates generally have a higher standard deviation than the overall unemployment rates in each geography, which are in turn generally more variable than urban unemployment rates. Higher volatility means we should be cautious about overinterpreting month-to-month movements in rural unemployment rates. However, it could also be a sign that rural workers face a more uncertain labor market compared to urban workers.

| Geography | Rural | Overall | Urban |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| MD | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| NC | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| SC | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| VA | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| WV | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| 5th District | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Note: "Overall" column uses Current Population Survey-based estimates rather than Local Area Unemployment Statistics estimates. Source: Author's calculations using Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Labor Statistics data via Haver Analytics. |

|||

Higher unemployment rates and more labor market uncertainty in rural communities highlights the reality that rural communities grapple with economic challenges that are distinct from those of their urban neighbors. Understanding these challenges is key to the Fed's public mission. For example, the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act requires the Fed to encourage financial institutions to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they do business, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

While the data highlight some broad patterns in rural unemployment rates, the Richmond Fed also supplements the data with on-the-ground anecdotes obtained through outreach to rural communities. Further information on the Richmond Fed's rural initiatives can be found at its Region and Communities page.

The Fifth Federal Reserve District — which is served by the Richmond Fed — is composed of most of West Virginia and all of North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.

The BLS cautions data users that "estimates not directly derived from sample surveys or statistical modeling are subject to errors resulting from the estimation processes used and from the limitations of the data sources used. The error structure associated with these estimates is complex, and information on the magnitude of overall errors is not available." Due to these limitations, the urban and rural unemployment rates discussed in this post should be interpreted as providing qualitative evidence regarding directional trends, rather than representing precise quantitative metrics.

Because the underlying data are not seasonally adjusted, I adjust the estimated unemployment rates for seasonality using the Census Bureau's X-13ARIMA-SEATS procedure.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.