Uncertain Outlook for Disabled Employment

Note: According to the National Institutes of Health, there is an evolving view between person-first (i.e., "persons with disabilities") and identity-first language (i.e., "disabled persons") within the disability community. For the purposes of this post, we use terms interchangeably.

Last week's post discussed recent tailwinds to labor supply stemming from immigrant labor. However, the foreign-born are not the only demographic that has seen increased labor force participation.

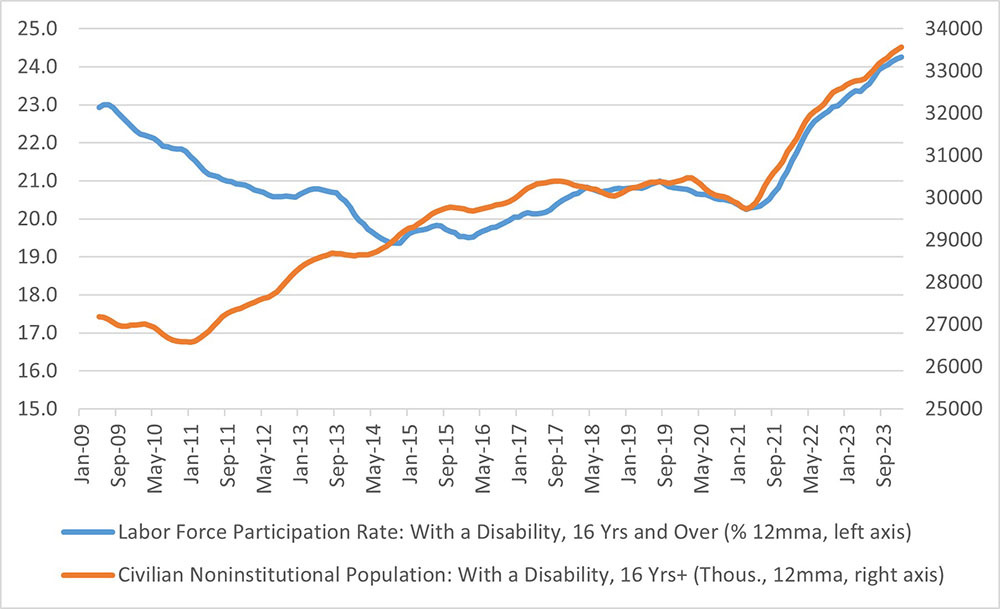

Since 2021, there has been a large increase in both the size of the population with disabilities and the disabled labor force participation rate as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Figure 1 below shows that the population with disabilities has increased by over 10 percent since the start of the pandemic, while the participation rate has increased by roughly 4 percentage points.

The BLS estimates of the disabled population are from its Current Population Survey (CPS), which identifies a person with a disability as someone who reports at least one of the following conditions:

- Is deaf or has serious difficulty hearing.

- Is blind or has serious difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses.

- Has serious difficulty concentrating, remembering or making decisions because of a physical, mental or emotional condition.

- Has serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs.

- Has difficulty dressing or bathing.

- Has difficulty doing errands alone such as visiting a doctor's office or shopping because of a physical, mental or emotional condition.

According to a study by Ari Ne'eman and Nicole Maestas, the increase in CPS-measured disabled labor force participation may reflect the effect of long COVID and other new sources of disability, "suggesting that [persons with disabilities' (PWD)] improved labor force participation is the result of an influx of new PWD with comparably mild impairments, more social and professional capital, and a greater attachment to the labor force." The authors also find that levels of disabled workers recovered rapidly following the pandemic recession, with employment gains concentrated in remote work occupations.

The authors' findings suggest that the expansion of remote and hybrid work arrangements after the pandemic have increased opportunities for people with disabilities to work and remain in the labor force. This would be consistent with other evidence from the CPS that points to a disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the labor choices of the disabled population.

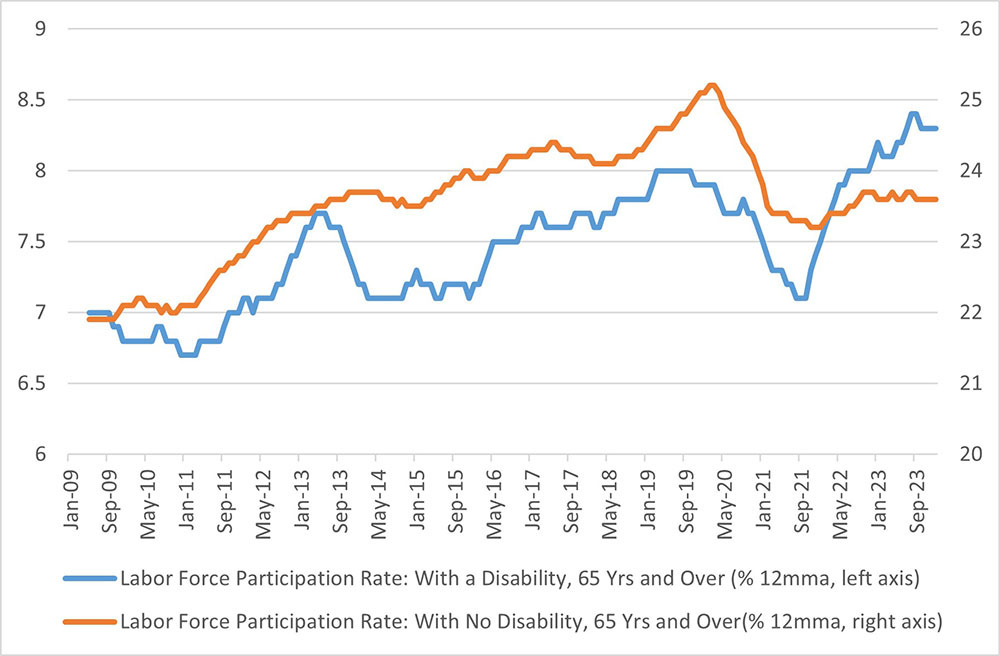

One area where the difference is particularly stark is for the older (age 65 and up) workforce. For this group, health concerns during the pandemic led to an increase in retirements and a decline in labor force participation. However, Figure 2 below shows that while this narrative is true for the older labor force with no disabilities, labor force participation actually increased for the older labor force with disabilities, rising about half a percentage point compared to pre-pandemic levels.

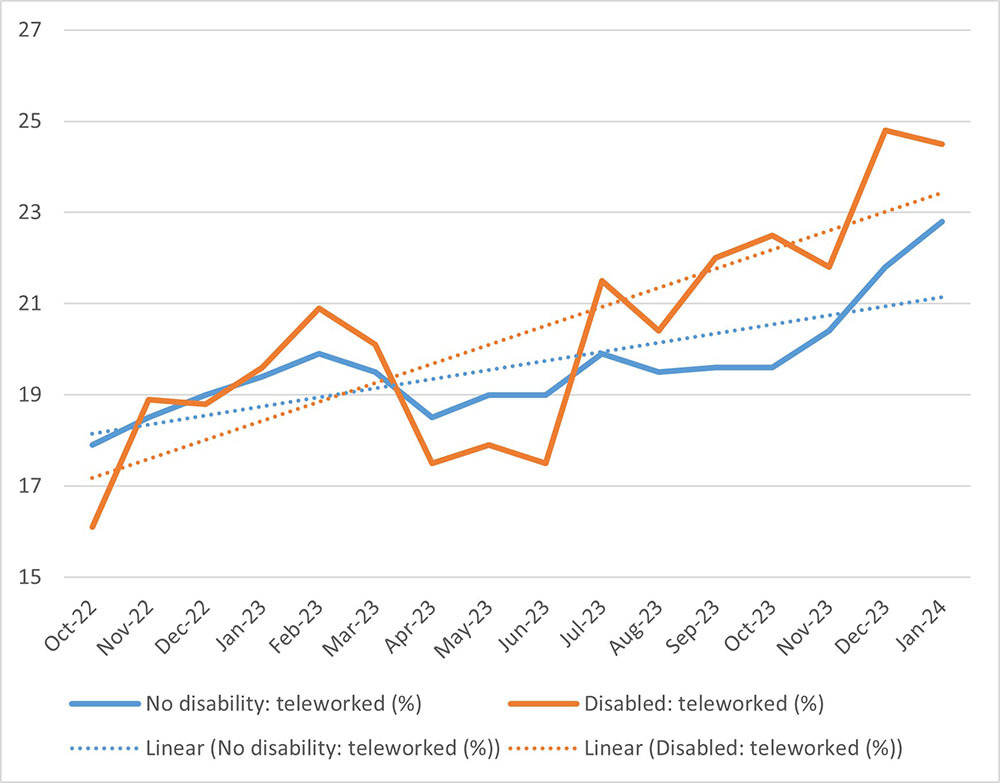

CPS data also point to increased uptake of remote work for workers with disabilities. Starting in October 2022, the BLS added questions to the CPS asking whether people teleworked or worked at home for pay. Responses to these questions show that the share of disabled workers teleworking is now larger than the share of workers reporting no disability who teleworked, with the gap between the two demographics seems to be widening in recent data (though the small sample size of disabled persons makes it difficult to draw statistical inferences). This trend suggests disabled workers are increasingly choosing to work in occupations that offer remote work capabilities.

The path ahead for participation for workers with disabilities is unclear. Recent news headlines suggest that employers continue to announce return-to-office mandates. The extent to which the end of remote work dampens the participation of the disabled workforce is still highly uncertain and could represent a negative risk to labor supply, despite ongoing indications that the labor market remains tight.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.