Understanding Recent Trends in Labor Market Participation

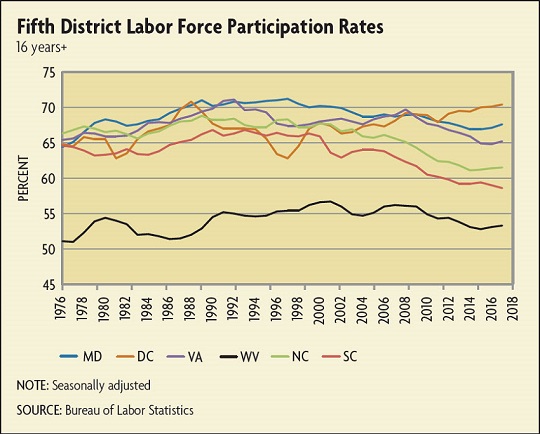

By many metrics, the labor market is very tight. The national unemployment rate ended 2018 at a level not seen since the 1960s, while the unemployment rate for the Fifth District reached its lowest level since the first half of 2000. The number of job openings in the United Sates exceeds the number of workers looking for jobs, and the level of initial claims for unemployment insurance is near a 50-year low. Businesses indicate that finding and retraining workers is difficult. Yet the percentage of working-age adults in the country who are active in the labor market — the labor force participation rate — is below where it was prior to the Great Recession. A similarly broad metric of the labor market that compares the number of employed persons in the country to the working-age population, the employment-to-population ratio, also remains well below prerecession levels. Do these metrics imply that the labor metric is not as tight as thought — that there is additional slack? Are there workers who left the labor market and are available to return should the right opportunity arise?

Some point to the fact that wages have increased only moderately and wage growth remains below rates during other expansion periods as an indication that there is some additional slack in the labor market. The lack of wage growth has been unexpected — particularly given the drop in the unemployment rate from 10 percent to under 4 percent. When something becomes scarce or less abundant, all other things being equal, the price would be expected to rise. Perhaps what is muting the price increase is the availability of labor that is currently out of the labor force.

Another unexpected fact of the labor market in recent years has been the strength of the monthly job gains. Given population and labor force growth, the number of monthly job gains necessary to incorporate new entrants into the labor market is estimated to be between 50,000 and 110,000 jobs. Actual job growth in 2018 far surpassed this level at close to 225,000. In a tight labor market, with a low unemployment rate and labor scarcity, one would have expected to see greater moderation in the monthly job gains — but that has not happened. Perhaps the explanation, once again, is hidden slack: workers not in the labor market who are entering as opportunities arise.

In response to these questions, there has been a lot of research devoted to understanding movements in the labor force participation rate. It has been in decline since the late 1990s and that decline accelerated during the Great Recession and afterward. Is the accelerated decline due to transitory factors associated with the business cycle, changing trends in the demand for labor, changes in the demographic composition of the labor force, or some combination thereof? This article will review some of the research that examines the decline in these metrics and then look to see if this research helps explain the trends in the Fifth District.

A Look at the Trends

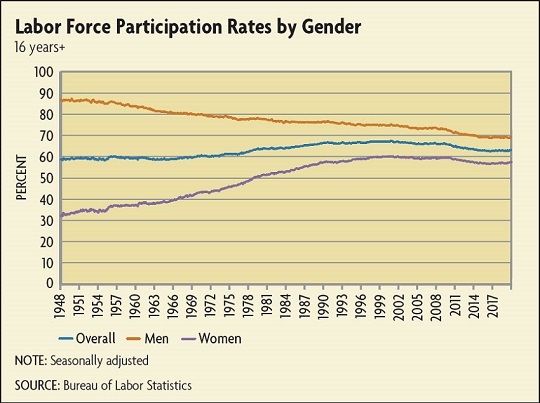

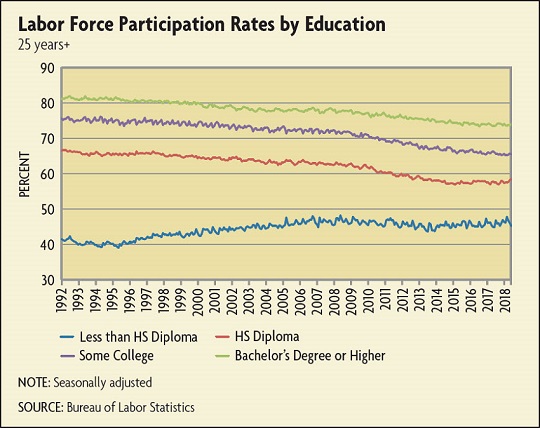

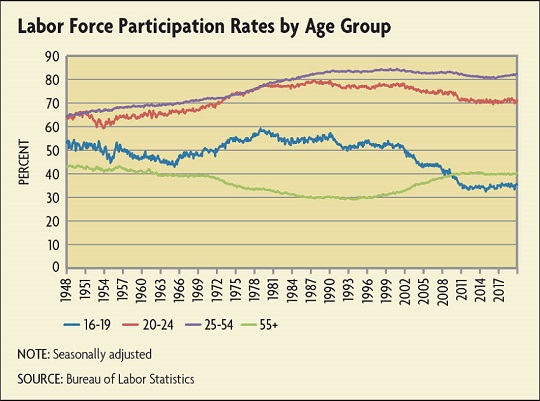

In the latter half of the 20th century, the percentage of workers engaged in the labor force rose considerably. The labor force participation rate increased by roughly 8 percentage points from the 1960s to 2000 — from just under 59 percent to just over 67 percent. The employment-to-population ratio experienced a similar increase over the same period. Underlying the increase in employment and the labor force were several factors: (1) a large demographic group entering the labor force — the baby boomers, (2) an increase in educational attainment, and (3) women entering the workforce in greater numbers. After peaking at 67.3 percent in early 2000, the labor force participation rate declined in two stages: gradually during the first half of the 2000s before leveling off just prior to the Great Recession and then more sharply during and after the Great Recession until reaching a 40-year low of 62.5 in 2015. It is notable that in 2017, the U.S. labor force participation rate for prime-age workers (aged 25 to 54) ranked 40th out of 50 among countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development — a fact that would perhaps surprise some as American culture is sometimes associated with a stronger emphasis on work and less on leisure than other cultures.

Underlying the overall decline are movements by various subgroups within the labor market. There are notable difference in trends by age group, gender, and educational achievement. The labor force participation rate for men has been in decline for many decades, while the rate for women rose consistently from 1960 to 1980 before slowing during the 1990s. (See chart below.) The participation rate for women peaked at 60.3 in early 2000 before declining to 56.4 in 2015 and has edged slowly higher in recent years.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.