The Fault in R-Star

Has the natural rate of interest lost its luster as a navigation aid for monetary policy?

In a 2018 speech at the annual Economic Policy Symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyo., Fed Chairman Jerome Powell compared monetary policymakers to sailors. Like sailors before the advent of radio and satellite navigation, Powell said, policymakers should navigate by the stars when plotting a course for the economy. Powell wasn't referring to stars in the sky, however. He was talking about economic concepts such as the natural rate of unemployment and the natural real interest rate. In economic models, these variables are often denoted by an asterisk, or star.

The natural rate of interest in particular sounds like the perfect star to guide monetary policy. The real, adjusted-for-inflation interest rate is typically represented in economic models by a lowercase "r." The natural rate of interest, or the real interest rate that would prevail when the economy is operating at its potential and is in some form of an equilibrium, is known as r* (pronounced "r-star"). It is the rate consistent with the absence of any inflationary or deflationary pressures when the Fed is achieving its policy goals of maximum employment and stable prices. Since the financial crisis of 2007-2008, Fed officials have often invoked r-star to help describe the stance of monetary policy. But lately, r-star seems to have lost some of its luster.

"Navigating by the stars can sound straightforward," Powell said in his Jackson Hole address. "Guiding policy by the stars in practice, however, has been quite challenging of late because our best assessments of the location of the stars have been changing significantly."

Even New York Fed President John Williams, who helped pioneer estimating r-star, recently bemoaned the challenges of using the natural rate as a guide for policy. "As we have gotten closer to the range of estimates of neutral, what appeared to be a bright point of light is really a fuzzy blur," he said in September 2018.

Why did r-star become so prominent in monetary policy discussions following the Great Recession, and why have its fortunes seem to have waned?

"Lubik-Matthes Natural Rate of Interest," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

"How Likely is the Zero Lower Bound?" Economic Quarterly, First Quarter 2019.

"Monetary Policy with Unknown Natural Rates," Economic Brief No. 11-07, July 2011.

A Star is Born

The concept of the natural rate of interest dates back more than 100 years. In an 1898 book titled Interest and Prices: A Study of the Causes Regulating the Value of Money, Swedish economist Knut Wicksell argued that one could not judge inflation by looking at interest rates alone. High market rates did not necessarily mean that inflation was speeding up, as was commonly believed at the time, nor did low rates mean that the economy was experiencing deflation. Rather, inflation depended on where interest rates stood relative to the natural rate.

Wicksell's natural rate seemed like an ideal benchmark for monetary policy. The central bank could slow down an economy in which inflation was accelerating by steering interest rates above the natural rate, while aiming below the natural rate could help stimulate an economy that had fallen below its potential. Indeed, Fed officials in the past made occasional reference to the natural rate of interest as a way to explain monetary policy. During testimony before Congress in 1993, then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan explained that "in assessing real rates, the central issue is their relationship to an equilibrium interest rate… Rates persisting above that level, history tells us, tend to be associated with slack, disinflation, and economic stagnation — below that level with eventual resource bottlenecks and rising inflation, which ultimately engenders economic contraction."

Despite some passing references to the natural rate of interest, however, Wicksell's idea didn't truly rise to prominence until the early 2000s when Columbia University economist Michael Woodford incorporated it into a modern macroeconomic framework to describe how central banks should behave. In his book, titled Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy in a nod to Wicksell's work, Woodford argued that a central bank should seek to close the gaps between actual economic conditions and the economy's potential for output and employment (y-star and u-star, respectively) as well as the gap between actual real interest rates and the natural rate (r-star) all at the same time to obtain an optimal outcome. There was just one problem: No one knows exactly what r-star, or any of the stars, is equal to.

"R-star, just like potential GDP or the natural rate of unemployment, is fundamentally unobservable," says Thomas Lubik, a senior advisor in the research department at the Richmond Fed.

In 2003, New York Fed President Williams, then an economist at the San Francisco Fed, and Thomas Laubach, an economist with the Fed Board of Governors, published a paper in the Review of Economics and Statistics that attempted to estimate the natural rate of interest.

"The paper was highly cited, but it took some time before policymakers began to view r-star as a potential operational guide," says Lubik.

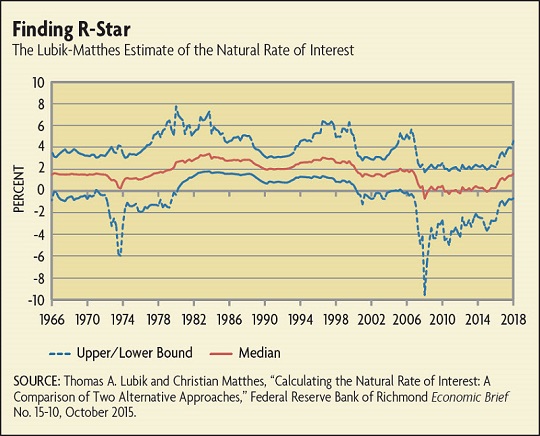

From the perspective of monetary policymakers, a key problem was that estimates of r-star are highly uncertain. This can be seen in the r-star measure developed by Lubik and fellow Richmond Fed economist Christian Matthes. Their median estimate represents the most likely value of r-star, which was 1.56 percent at the end of 2018, but that estimate exists in a range of potential values. (See chart below.) The inability to measure the natural rate of interest precisely seemed to limit its usefulness as a benchmark for setting monetary policy. But after the Great Recession, policymakers began to take a closer look at r-star.

Readings

Borio, Claudio, Piti Disyatat, and Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul. "What Anchors for the Natural Rate of Interest?" Paper prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston 62nd Annual Economic Conference, Sept. 7-8, 2018.

Del Negro, Marco, Domenico Giannone, Marc P. Giannoni, and Andrea Tambalotti. "Safety, Liquidity, and the Natural Rate of Interest." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2017, pp. 235-316.

Laubach, Thomas, and John C. Williams. "Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest." Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2003, vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 1063-1070.

Lubik, Thomas A., and Christian Matthes. "Calculating the Natural Rate of Interest: A Comparison of Two Alternative Approaches." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief No. 15-10, October 2015.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.