Are CEOs Overpaid?

Incentives for chief executives have important economic implications

The 2019 proxy season will mark the second year firms have to disclose how their CEOs' compensation compares to the pay of their median employee. The ratios are likely to generate quite a few headlines, as they did last year, and perhaps some outrage, especially in light of relatively stagnant wage increase for most workers in recent years. (See "Will America Get a Raise?" Econ Focus, First Quarter 2016.) But do CEOs actually earn hundreds, or even thousands, of times more money than their employees? And does that necessarily mean they're paid too much?

Calculating CEO Pay

It should be easy to determine how much CEOs earn. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires publicly traded companies to disclose in detail how they compensate their chief executives, including base salaries, bonuses, stock options, stock grants, lump-sum payments such as signing bonuses, and retirement benefits. Firms are also required to report any perks worth more than $10,000, such as use of the corporate jet or club memberships, that aren't directly related to the executive's job duties.

The challenge for researchers is that some forms of compensation, such as stock options, can't be turned into cash until some later date. That means there's a difference between expected pay — the value of compensation on the day it's granted, which depends on the current market value of the stock and expected value of stock options — and realized pay, or what a CEO actually receives as a result of selling stock or exercising options.

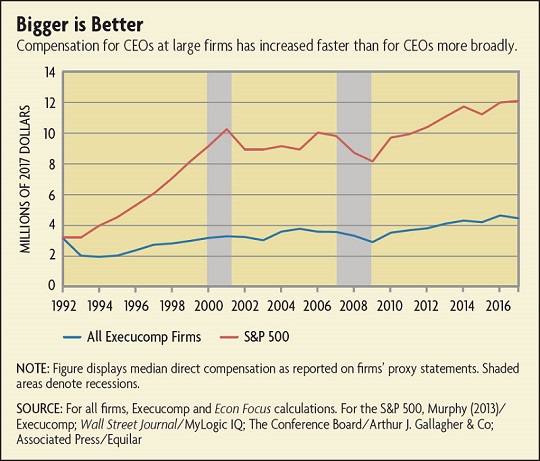

One widely used measure of expected pay comes from the Execucomp database, which is published by a division of Standard and Poor's. The database includes about 3,000 firms, including current and former members of the S&P 1500, and contains information gleaned from firms' proxy statements. Between 1993 and 2017, according to Execucomp, median CEO pay increased more than 120 percent in inflation-adjusted terms. (The Execucomp data begin in 1992, the year before Congress passed a law limiting the tax deductibility of CEO compensation.) The increase was greater for bigger firms: Median CEO pay in the S&P 500 increased 275 percent, from $3.2 million to $12.1 million, in 2017 dollars. (See chart below.) Over the same time period, median wages for workers overall increased just 10 percent.

"Optimal Incentive Contracts with Job Destruction Risk," Working Paper No. 17-11, October 2017.

"The Complexity of CEO Compensation," Working Paper No. 14-16, September 2014.

The CEO Multiplier

How much do CEOs earn relative to their employees? According to the AFL-CIO, the average CEO of a company in the S&P 500 earned $13.94 million in 2017 — 361 times more than the average worker's salary of $38,613. (To calculate the average worker's salary, the AFL-CIO uses Bureau of Labor Statistics data on the wages of production and nonsupervisory workers, who make up about four-fifths of the workforce.) But this ratio may be overstated for several reasons. One is that the AFL-CIO uses average CEO pay, which is typically much higher than median pay because of outliers. Another is that the data used for CEO compensation include nonsalary benefits, while the data for average workers include only salary. In addition, workers' salaries aren't adjusted for firm size, industry, or hours worked, so a CEO who works 60-hour weeks at a company employing 50,000 people is compared to, say, a part-time bookkeeper at a firm employing 10 people. Still, even adjusting for hours worked and fringe benefits, CEOs earn between 104 and 177 times more than the average worker, according to Mark Perry of the University of Michigan-Flint and the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

The pay ratio required by the Dodd-Frank Act does take into account firm size and industry, since it compares CEOs to the median workers at their own companies. According to the corporate governance consultancy Equilar, the median pay ratio in 2017 was 166 to 1 for the 500 largest publicly traded companies by revenue. Among a broader group of 3,000 publicly traded firms, the median pay ratio was 70 to 1. But this comparison can be skewed in one direction if a CEO receives a large one-time payment, or in the other direction if a CEO declines all compensation, as do the chief executives at Twitter, fashion company Fossil, and several other firms. (Twitter's and Fossil's CEOs both have significant stock holdings in the firms.) In addition, pay ratios might appear especially high at companies with a large number of part-time or overseas employees, who tend to earn lower annual wages.

Power and Stealth

Until the turn of the 20th century, most firms were small and run by their owners. But between 1895 and 1904, nearly 2,000 small manufacturing firms merged into 157 large corporations, which needed executives with specialized management skills. These executives didn't have equity stakes in the companies, which created a "separation of ownership and control," as lawyer Adolf Berle and economist Gardiner Means described in their seminal 1932 book, The Modern Corporation and Private Property.

In modern economics terms, this creates what is known as a "principal-agent" problem. A manager, or agent, has wide discretion operating a firm but doesn't necessarily have the same incentives as the owners, or principals, and monitoring is unfeasible or too costly. For example, a CEO might try to avoid a takeover even if that takeover is in the shareholders' best interest. Certainly, managers are motivated by career concerns, that is, proving their value to the labor market to influence their future wages. But the primary approach to aligning managers' and shareholders' interests has been to make the executive's pay vary with the results of the firm, for example via stock ownership or performance bonuses. (Of course, this can go awry, as it famously did when executives at the energy company Enron engaged in fraudulent accounting to boost short-term results.)

At the same time, a talented CEO is unlikely to want to work for a company without some guarantee of compensation in the event of circumstances beyond his or her control, such as regulatory changes or swings in the business cycle. So firms also have to provide some insurance, such as a base salary or guaranteed pension.

In theory, a company's board of directors acts in the best interest of shareholders and dispassionately negotiates a contract that efficiently balances incentives and insurance, which economists refer to as "arm's-length bargaining." But as Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried of Harvard Law School described in their 2004 book Pay Without Performance, there may be circumstances when CEOs are able to exert significant influence over their pay packages. This might happen because the CEO and the directors are friends, or because the chief executive has a say in setting board compensation and perks, or because the directors simply don't have enough information about the firm's operations. And if the shareholders' power is relatively weak, they are unlikely to check the directors. Bebchuk and Fried cited research finding that CEO pay is lower when investors have larger stakes, and thus more control, and when there are more institutional investors, who are likely to spend more time on oversight.

Even when CEOs have a lot of power, they and their boards might still be constrained by what Bebchuk and Fried called "outrage costs," or the potential for obviously inefficient pay packages to damage the firm's reputation. That can lead to "stealth compensation," or compensation that is difficult for investors or other outsiders to discern. In the 1990s, for example, it was common for firms to give their CEOs below-market-rate loans or even to forgive those loans. (These practices were outlawed by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002.) And until the SEC tightened pension disclosure rules in 2006, firms could give CEOs generous retirement benefits without reporting their value. CEOs might also receive stealth compensation in the form of dividends paid on unvested shares.

Stealth compensation does face some constraints, as Camelia Kuhnen of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Jeffrey Zwiebel of Stanford University found in a 2009 article. For example, hidden compensation could be sufficiently large and inefficient to weaken a firm's performance and lead the shareholders to fire the CEO. Kuhnen and Zwiebel concluded that CEOs are more likely to earn stealth compensation when a firm's production process is "noisy," meaning it's difficult to determine the factors that contribute to the firm's performance.

Talent and Value

While some research suggests that CEOs' pay reflects their power over their boards, other research suggests they're worth it. (The two explanations aren't necessarily mutually exclusive — a CEO could significantly increase shareholder value while still influencing a board to pay more than the market rate.) In a 2016 article, Alex Edmans of London Business School and Xavier Gabaix of Harvard University summarize the research on the latter perspective as the "shareholder value" view. In short, from this perspective, CEOs' contracts reflect their significant influence on a company relative to rank-and-file employees and the fact that it may be necessary to pay a premium to attract talent in a competitive market.

In this view, one explanation for high and rising CEO pay might be technological change. In a 2006 article, Luis Garicano of the London School of Economics and Political Science and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg of Princeton University described firms as "knowledge hierarchies," in which workers specialize in either production or problem solving. The hardest problems eventually filter up to the workers with the most knowledge, and new tools that make it cheaper to communicate means that firms rely more on problem-solvers, which decreases the knowledge necessary for production work. The end result is higher pay for those at the top of the hierarchy.

It's also well-documented that CEO pay increases with firm size, which could be the result of a CEO's ability. For example, more-talented CEOs might be able to hire more people and purchase more capital equipment, enlarging their firms. In addition, the dollar value of a more-talented CEO is higher at a larger firm. So when firms get bigger on average, the competition for talented CEOs increases. In a 2008 article, Gabaix and Augustin Landier of HEC Paris and the Toulouse School of Economics concluded that the increase in CEO pay in the United States between 1980 and 2003 was fully attributable to large companies' increase in market capitalization over the same time period. In addition, in a market where both CEO positions and talented CEOs are rare, even very small differences in talent can lead to large differences in pay, according to research by Marko Terviö of Aalto University in Finland — although Terviö also notes this does not necessarily mean that CEOs aren't "overpaid."

Unintended Consequences

The composition and level of CEO pay might reflect not only power and talent, but also the consequences — often unintended — of government intervention. Between 1993 and 2001, median CEO pay more than tripled, driven almost entirely by increases in stock options, according to research by Kevin J. Murphy of the University of Southern California. The increase in stock options, in turn, was fueled by several tax and accounting changes that made options more valuable to the executive and less costly to the firm. In 1991, for example, the SEC made a rule change that allowed CEOs to immediately sell shares acquired from exercising options. Previously, CEOs were required to hold the shares for six months and could owe taxes on the gain from exercising the option even if the shares themselves had fallen in value. And in 1993, Congress capped the amount of executive compensation publicly held firms could deduct from their tax liability at $1 million unless it was performance based, with the goal of reducing "excessive" compensation. (The cap applied to the five highest-paid executives.) But stock options were considered performance based and thus were deductible. The cap also induced some companies to raise CEO salaries from less than $1 million to exactly $1 million.

Regulators took steps that curbed the use of option grants in 2002, when the Sarbanes-Oxley Act tightened the reporting standards, and again in 2006, when the Financial Accounting Standards Board mandated that they be expensed. Both of these changes decreased the attractiveness of stock options relative to stock grants, which led some firms to stop awarding options and others to start granting stock in addition to options, according to research by Jarque with former Richmond Fed research associate Brian Gaines.

Regulation might also have increased the use of perquisites in the 1980s. In the late 1970s, the SEC started requiring more disclosure of perks such as entertainment and first-class air travel; one SEC official said the "excesses just got to the point where it became a scandal." But as Murphy and others have documented, the disclosure rules actually increased the use of perquisites (although they remained a fairly small portion of total compensation), as executives learned what their peers at other firms were receiving.

Since 2011, large publicly traded firms have been required to allow their shareholders a nonbinding vote on executive pay packages. The goal of "Say on Pay," which was part of the Dodd-Frank Act after the financial crisis, was to rein in executive compensation and enable shareholders to tie pay more closely to performance. (See "Checking the Paychecks," Region Focus, Fourth Quarter 2011.) But research by Jill Fisch of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Darius Palia of Rutgers Business School, and Steven Davidoff Solomon of Berkeley Law suggests shareholders are highly influenced by the company's performance; that is, they tend to approve pay packages when the stock is doing well. That could encourage executives to focus on the short-term stock price rather than the firm's long-term value. Other research has found that Say on Pay has made firms more reliant on outside compensation experts, who tend to design homogenous pay packages geared toward shareholder approval rather than what's most effective for the firm.

Does CEO Pay Matter?

"CEO pay can have substantial effects, which spill over into wider society," says Edmans. "Incentives can backfire with severe societal consequences. In contrast, well-designed incentives can encourage CEOs to create value — and hold accountable those who do not."

In the 1970s, for example, CEOs were largely rewarded for making their companies bigger — at the expense of their firms' value, according to Murphy. "The implicit incentives to increase company revenue help explain the unproductive diversification, expansion, and investment programs in the 1970s, which in turn further depressed company share prices," he wrote in a 2013 article.

More recently, many observers and researchers believe that compensation practices played a role in the financial crisis. As Scott Alvarez, former general counsel of the Fed, observed in 2009 testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, "Recent events have highlighted that improper compensation practices can contribute to safety and soundness problems at financial institutions and to financial instability." Many of these practices also applied to lower-level executives and employees, but CEOs might have been incentivized to ignore the risks their employees were taking.

There is also the question of fairness. To the extent high pay is the result of managerial power or efforts to take advantage of tax laws, rather than the result of higher output or performance, workers might not be getting their share of the fruits of economic growth. This is an opinion that's been voiced since at least the early 1930s, when the public first started to learn what executives were paid as the result of a series of lawsuits. Recently, some research attributes the rise in income inequality at least in part to executive compensation, although, as Edmans notes, the top 1 percent comprises many professions, including lawyers, bankers, athletes, authors, pop stars, and actors, to name a few. In Edmans' view, fairness isn't necessarily the right reason to be concerned about CEO pay. "Often people care about CEO pay because there's a pie-splitting mentality — the idea that there's a fixed pie and anything given to the CEO is at the expense of others," he says. "But if we have a pie-growing mentality, we should care because the correct incentives affect the extent to which the CEO creates value for society."

Readings

Bebchuk, Lucien Arye, and Jessie M. Fried. "Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem." Journal of Economic Perspectives, Summer 2003, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 71-92.

Edmans, Alex, and Xavier Gabaix. "Executive Compensation: A Modern Primer." Journal of Economic Literature, December 2016, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 1232–1287.

Jarque, Arantxa, and John Muth. "Evaluating Executive Compensation Packages." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Fourth Quarter 2013, vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 251-285.

Murphy, Kevin J. "Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There." In Constantinides, George M., Milton Harris, and Rene M. Stulz (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Finance, vol. 2, part A. Amsterdam: North Holland, 2013.

Wells, Harwell. "'No Man Can Be Worth $1,000,000 A Year': The Fight over Executive Compensation in 1930s America." University of Richmond Law Review, January 2010, vol. 44, pp. 689-769.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.