Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University

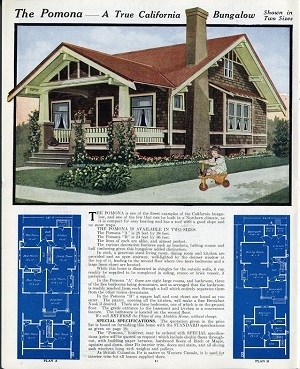

The "Pomona" in Aladdin’s 1920 catalog

During the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of Americans bought homes through mail-order catalogs. Prospective homeowners picked out a design, and the manufacturer shipped them everything they needed to build it, along with detailed blueprints. (Sears, Roebuck and Company, the best-known kit home purveyor, sent the blueprints in a leather book embossed with the buyer's name.) Many homeowners built the homes themselves; Sears estimated that a "man of average abilities" could complete one of their houses in 90 days.

"Imagine getting a letter that says, 'Your house will be on the train three days from now. Go down to the depot and unload your box car,'" says architectural historian Rebecca Hunter, who has written several books about kit homes. "It's so weird and wonderful."

On the designated day, the new homeowners would arrive at the train station and begin unloading the materials they would use to build their new home. Over the next several days, they would transport (in an automobile, if they were lucky) lumber, nails, shingles, windows, doors, pipes, and even doorknobs to their home site. The materials for Sears Modern Home #111, a two-story foursquare home called the "Chelsea," included 25 doors, 28 windows, 750 pounds of nails, 325 feet of crown molding, and six dozen coat hooks.

Sears and other companies marketed their homes to buyers of "modest means"; advertisements emphasized the low cost and described the homes as "practical" and "for everybody." In an era where single-family housing was still relatively rare, mail-order homes were a way for middle-class families to attain a previously unaffordable goal of homeownership. In addition, Sears and some other manufacturers offered financing for the kits, and the applications didn't ask about race, gender, or ethnicity. This may have made it easier for immigrants, minorities, and single women to purchase homes, since they faced discrimination from other mortgage lenders of the time (although they might still have been restricted, formally or informally, from purchasing lots in many places). Existing records don't enable historians to determine the composition of kit-home buyers, but anecdotal evidence suggests that some people who couldn't obtain financing from traditional sources were able to obtain it from Sears.

A modern-day analog to kit homes is manufactured housing. These homes are assembled in a factory and then shipped to the site and tend to cost significantly less than traditional site-built homes. With housing affordability an increasing challenge for even middle-class families, observers ranging from industry trade groups to affordable housing advocates are looking to manufactured housing as a potential solution.

Building a Market

In the late 1880s, former railroad station agent Richard Sears started selling watches through the mail with Alvah Roebuck, a watchmaker and repairman. They incorporated as Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1893, and by the following year, their catalog was 322 pages long and sold everything from syringes to refrigerators. By 1908, when Sears started its Modern Homes program, more than one-fifth of Americans subscribed to a catalog that at its peak advertised 100,000 items on 1,400 pages.

Sears started selling construction materials in 1895, but the division languished unprofitably until Frank Kushel, previously the head of the company's china department, took over in 1906. He realized Sears was losing money by paying to store the materials before they were shipped to buyers and proposed something new: shipping the goods directly from the factories to the customers.

The first Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans was published in 1908 with 22 different homes. At first, Sears sold only bulk materials and the blueprints, but in 1915 the company started offering complete kits that included precut lumber numbered to match the plans; windows, doors, and flooring; and even the exact number of nails needed. (Plumbing fixtures, for homes that included an indoor bathroom, were available for an extra charge.) Eventually, Sears offered 447 different plans in three product lines, ranging from the most expensive "Honor Bilt" homes, some of which had two stories, to "Simplex Sectional" garages and farm buildings. For little or no additional charge, Sears' architects would modify the plans upon request — reversing a floor plan, for example, or adding extra dormers.

Kit homes were made possible by a variety of new construction techniques. In the late 1800s, many residential roofs were made of large sheets of felt covered with pine tar and asphalt. But in 1903, roofing contractor Henry Reynolds started cutting these rolls into individual shingles, which were much easier to ship and install. Also in the 1800s, the timbers in a home's frame were connected using mortise-and-tenon joints, which required advanced carpentry skills. But by the end of the century, "balloon" framing was in widespread use. With this technique, a house could be framed with precut two-by-fours and two-by-sixes that ran straight from the floor to the roof and could be nailed together. The invention of drywall in 1916 also dramatically simplified home construction. Before drywall, wood walls were covered with layers of plaster, a skill- and time-intensive process. But sheets of drywall could be manufactured and shipped in large quantities and installed by someone with "average abilities."

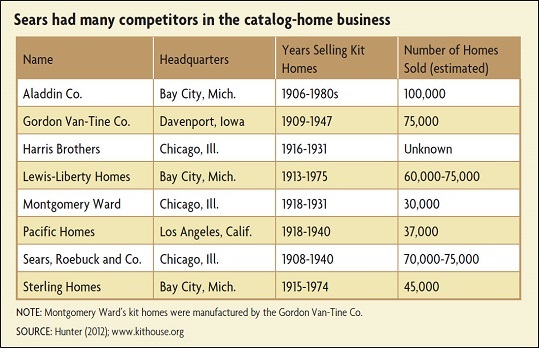

Sears didn't keep its sales records, so no one knows exactly how many Sears homes were built. By most estimates, the company sold between 70,000 and 75,000 homes from 1908 to 1940, when the Modern Homes division closed its doors, although some estimates are higher. Overall, Hunter estimates that the kit homes sold by Sears and other manufacturers accounted for between 2 percent and 5 percent of housing starts in the 1920s.

Sears' homes sales reached $12.5 million in 1929 — but nearly half of that value was in financing, which the company had started offering in 1911. (The typical Sears loan required a 25 percent down payment, with a five-year repayment period at 6 percent interest. Sometimes Sears would extend the period to as long as 15 years.) During the Great Depression, Sears had to foreclose on many of its customers; it liquidated $11 million in loans in 1934. Although Sears continued to sell homes for the remainder of the decade, it no longer offered financing and sales steadily declined. The final Sears house catalog was issued in 1940.

Catalog Competitors

"Sears home" has largely become synonymous with "kit home." But that's deceiving. "Sears wasn't the first to start selling kit houses, they weren't the last company out of the market, and they didn't sell the most homes," says Hunter. As early as 1866, the Lyman Bridges Company of Chicago sold prefabricated "sectionalized" homes to settlers in the West. And Sears' Frank Kushel actually got the idea for selling kits from brothers William and Otto Sovereign, who founded the North American Construction Company in Bay City, Mich., in 1906.

The Sovereign brothers, who later renamed their company Aladdin, started out making kits for boat houses, garages, and summer cottages. Aladdin would become Sears' largest competitor; between 1913 and 1927, they sold around 2,000 homes per year, peaking at 3,650 in 1926.

Aladdin didn't just sell individual homes — it also sold entire communities. More than 300 corporations built company towns with homes purchased in bulk from Aladdin's Low Cost Homes Designed Especially for Industrial Purposes catalog. One such corporation was DuPont, which in 1914 signed a contract with France to produce 8 million pounds of guncotton, a smokeless propellant that replaced gunpowder during World War I. More Allied orders followed, and DuPont quickly built three new factories near its small dynamite factory in Hopewell, Va. To help house its workers, DuPont ordered hundreds of Aladdin homes, dozens of which are still standing.

DuPont also built Aladdin kit homes for World War I-era munitions workers in Sandston, Va., outside Richmond, and in Penniman, Va., on the York River near Williamsburg. Penniman was largely abandoned after World War I, but some of its Aladdin homes were shipped to Norfolk via barge, where they remain today.

In 1925, Aladdin purchased a parcel of land south of Miami, Fla., and started building "Aladdin City," which was designed to house 10,000 residents. But Florida was at the peak of a real estate boom, and that same year, overwhelmed by delivering building materials, the railroads refused to transport anything besides food and other essentials. Development across the state slowed, prices started to decline, and the boom went all the way bust after a major hurricane in 1926. Aladdin's development went dormant, and the venture was officially dissolved in 1936. It continued to sell a few hundred kit homes per year through the 1970s but never fully recovered. It went out of business in the 1980s, having sold around 100,000 homes in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Africa.

Other major manufacturers of kit homes included Lewis-Liberty Homes and Sterling Homes, both based in Aladdin's home town of Bay City, Mich.; Gordon Van-Tine of Davenport, Iowa; Chicago's Harris Brothers; California-based Pacific Homes; and Sears catalog competitor Montgomery Ward, which also offered mortgage financing and, like Sears, saw the Great Depression put an end to its housing division. (See table below.)

Courtesy of Catarina Bannier/DC House Smarts

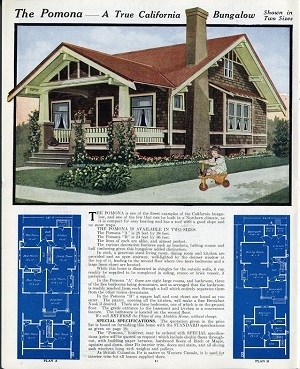

A Pomona that sold for nearly $1.4 million in Washington, D.C., in 2017.

Washington, D.C., is a case in point. Between 1914 and 1919, the city's population grew from around 350,000 to more than 520,000, as World War I drew soldiers, civilian volunteers, lobbyists, and new federal workers to the city. The city was served by several railroads, and multiple streetcar lines had spurred the development of suburbs such as Mount Pleasant, Anacostia, and Chevy Chase. More than 300 Sears homes have been identified in Washington, D.C., and Washington real estate agents Catarina Bannier and Marcie Sandalow estimate that there are hundreds more by other manufacturers throughout the city. They have authenticated about 100 kit homes in the Chevy Chase neighborhood alone. In 2017, a "Pomona" model by Aladdin in Northwest Washington sold for nearly $1.4 million.

Aladdin's 1915 catalog advertised the Pomona for $1,365; a second floor was available for an additional $138.

Manufactured Affordability

Plenty of pricey homes have been sold in Washington, D.C., recently. In June 2019, median home prices reached $620,000, a new record for that month. A similar story is occurring across the country: Nationwide, housing prices are 15 percent above the 2006 peak, pushed up by a lack of supply and rising costs for labor and materials. (See "The Missing Boomerang Buyers," Econ Focus, First Quarter 2017.) This is especially true for the lower end of the market; since 2014, prices have increased faster for the bottom fifth of homes than for homes overall.

The dearth of low- and mid-priced homes is driving renewed interest in factory-built housing, which is typically much less expensive than traditionally built homes. Not including land, the average new manufactured home costs $55 per square foot as of 2018. The average new site-built home costs $114 per square foot. Despite the low cost, manufactured homes account for only about 10 percent of housing starts, due in part to perceptions about quality, zoning restrictions, and traditional mortgage lenders' reluctance to offer financing.

Since the late 1970s, however, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has implemented a number of construction standards to improve the durability, safety, and energy efficiency of manufactured homes. And the Manufactured Housing Institute, a trade group, notes that technological advances have made it possible to produce a wide range of architectural styles and exterior finishes. In June 2019, a bipartisan group of senators introduced legislation that would allow state and local governments to include manufactured housing in their plans when they apply for HUD funding. The previous summer, Fannie Mae announced a new program to purchase loans for manufactured homes that met certain criteria, with the goal of making more financing available. Freddie Mac has launched a similar program as part of its "Duty to Serve" initiative, which focuses on affordable housing and underserved markets. But to be eligible for either program, homes must have features including permanent foundations, pitched roofs, and architectural details such as porches or dormers. Such homes typically cost between $150,000 and $250,000 and thus still may be out of reach for many households.

A million-dollar modernized Sears home is almost certainly out of reach for most households. But it's still possible for some people to live in Sears housing — after a fashion. Although the retailer filed for bankruptcy in 2018, its former catalog printing plant, in Chicago's Homan Square, has been redeveloped into 181 affordable apartment units.

Readings

Brocker, Michael, and Christopher Hanes, The 1920s American Real Estate Boom and the Downturn of the Great Depression: Evidence from City Cross-Sections." In White, Eugene N., Kenneth Snowden, and Price Fishback (eds.), Housing and Mortgage Markets in Historical Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. (Chapter available with subscription.)

Hunter, Rebecca L. Mail-Order Homes: Sears Homes and Other Kit Houses. Oxford, U.K.: Shire Publications, 2012.

Thornton, Rosemary. The Houses That Sears Built: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Sears Catalog Homes. Alton, Ill.: Gentle Beam Publications, 2004.