The Fed's Emergency Lending Evolves

The Fed is using emergency lending powers it invoked during the Great Recession to respond to COVID-19 — but it cast a wider net this time

As COVID-19 swept through the United States, the Fed reached for its playbook from the last major crisis in 2008-2009. Now, just as then, the central bank's actions have been aimed at restoring markets to normal functions during a major economic shock. In an emergency meeting on Sunday, March 15, the Federal Open Market Committee lowered the Fed's interest rate target to effectively zero and pledged to use its "full range of tools to support the flow of credit to households and businesses."

"The cost of credit has risen for all but the strongest borrowers, and stock markets around the world are down sharply," Fed Chair Jerome Powell told reporters in a press conference following the meeting. "Moreover, the rapidly evolving situation has led to high volatility in financial markets as everyone tries to assess the path ahead."

Many firms, both financial and nonfinancial, rely on short-term debt to keep their operations running smoothly. In a crisis, the normal market for credit can grind to a halt — and with it, the ability of these firms to borrow. Lenders find it difficult to assess the credit risk of borrowers when the economy is changing rapidly, and they have an incentive to hold onto liquid assets as insurance against uncertainty. To prevent a credit crunch from rippling throughout the economy, central banks often step in to act as a "lender of last resort" during crises — an emergency source of credit for otherwise solvent firms until normal credit market functions are restored.

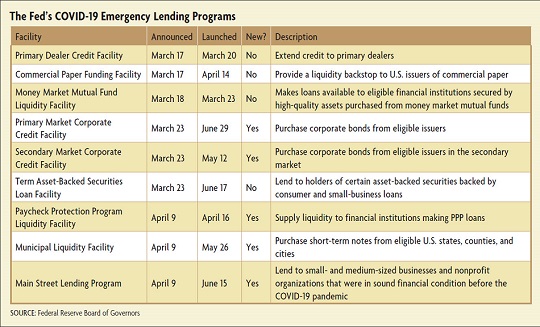

In keeping with this role, the Fed announced it would create several special lending facilities in the days following its March 15 meeting. Some of these were first used during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and retired after the recovery. The Fed also announced new facilities to lend to corporations, small businesses, and municipalities. (See table.)

"Federal Reserve MBS Purchases in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic," Economic Brief No. 20-08, July 2020

"Understanding Discount Window Stigma," Economic Brief No. 20-04, April 2020

"Optimal Liquidity Policy with Shadow Banking," Economic Theory No. 68, November 2019

Emergency Lending Makes a Comeback

In the decades after the Great Depression, the Fed invoked section 13(3) on a few occasions but did not actually make any loans. The emergency lending power remained unchanged and dormant until the passage of the 1991 FDIC Improvement Act, or FDICIA. The act removed the restriction that emergency loans could only be made against the same collateral accepted from banks at the discount window. Any securities that the Fed approved could now suffice as collateral.

As discussed in a 1993 article by Walker Todd, then an assistant general counsel and research officer at the Cleveland Fed, there was growing recognition among policymakers in the aftermath of the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and 1990s and the stock market crash of 1987 that liquidity crises could happen outside of the traditional banking sector. If the Fed lacked the tools to address those liquidity needs directly, such problems could spill out into financial markets, resulting in crises similar to the banking panics of the 19th century that the Fed was created to prevent.

This became apparent during the financial crisis of 2007-2008, when troubles at large nonbanks created liquidity problems for the whole financial system. For the first time since the 1930s, the Fed made emergency loans under section 13(3) to a variety of financial and nonfinancial firms when traditional credit markets seized up. These programs were open to all qualifying firms in broad segments of financial markets. The Fed also invoked section 13(3) to offer direct assistance to support the resolution of specific firms deemed "too big to fail." This included assisting in JPMorgan Chase's purchase of Bear Stearns and extending credit to American International Group to prevent its bankruptcy.

After the crisis subsided, legislators debated whether the Fed had gone too far in its emergency lending. Providing liquidity on a general basis seemed in keeping with the central bank's role as a lender of last resort, but providing direct assistance to specific firms was more controversial. It placed the Fed in the role of potentially picking financial winners and losers.

In the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, Congress placed new restrictions on the Fed's emergency lending powers. The Fed was no longer authorized to lend directly to individual firms. Instead, emergency loan facilities had to be available through a "program or facility with broad-based eligibility." Dodd-Frank also required that any emergency assistance needed to be "for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system, and not to aid a failing financial company." Finally, any loans the Fed made needed to be adequately secured to "protect taxpayers from losses," and the lending programs required "prior approval of the Secretary of the Treasury."

Fed officials supported these changes. In 2009 testimony before the House Committee on Financial Services, then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke acknowledged that the "activities to stabilize systemically important institutions seem to me to be quite different in character from the use of Section 13(3) authority to support the repair of credit markets." While he argued that directly intervening to stabilize systemically important firms was "essential to protect the financial system as a whole … many of these actions might not have been necessary in the first place had there been in place a comprehensive resolution regime aimed at avoiding the disorderly failure of systemically critical financial institutions."

At the same time, Bernanke and his successors supported giving the Fed some flexibility to respond to liquidity emergencies where and when they emerged.

"One of the lessons of the crisis is that the financial system evolves so quickly that it is difficult to predict where threats will emerge and what actions may be needed in the future to respond," Powell said in a 2015 speech while he was a Fed governor. "Further restricting or eliminating the Fed's emergency lending authority will not prevent future crises, but it will hinder the Fed's ability to limit the harm from those crises for families and businesses."

The Next Chapter

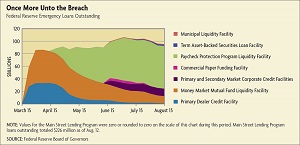

The Fed would call upon its emergency lending powers a few years later during the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, the Fed revived many of the same facilities it had used in 2007-2009 to make credit available to financial firms that can't access the discount window. But it also created new facilities to extend credit to a wider range of parties.

Through the Primary and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities, the Fed can purchase bonds directly from large, highly rated corporations and supply loans for companies to pay employees and suppliers. The Main Street Lending Program, announced in April and launched in June, offers five-year loans to businesses that are too small to qualify for the Fed's other corporate credit facilities. The Municipal Liquidity Facility makes loans available to state and local governments. And the Fed's largest new program to date is the Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility, which provides liquidity to financial institutions participating in the SBA's Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Businesses can take out loans through the PPP that can be forgiven if they use the money to retain workers on payroll. The Fed has agreed to provide credit to financial institutions making PPP loans, accepting those loans as collateral. Since the PPP loans are guaranteed by the federal government through the SBA, the Fed faces no risk of losses on this program.

Readings

Anderson, Haelim, Jin-Wook Chang, and Adam Copeland. "The Effect of the Central Bank Liquidity Support during Pandemics: Evidence from the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic." Federal Reserve Board of Governors Finance and Economics Discussion Series No. 2020-050, June 5, 2020.

Mehra, Alexander. "Legal Authority in Unusual and Exigent Circumstances: The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis." Journal of Business Law, Fall 2010, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 221-273.

Menand, Lev. "Unappropriated Dollars: The Fed's Ad Hoc Lending Facilities and the Rules that Govern Them." ECGI Working Paper Series in Law No. 518/2020, May 2020.

Sastry, Parinitha. "The Political Origins of Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act." Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, September 2018.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.