How Do Demographics Influence r*?

Demographic trends are evolving in the U.S. as well as globally, potentially affecting the behavior of interest rates. This includes the natural rate of interest, denoted r*. Through the lens of a simple model, we describe supply and demand channels through which these demographic trends may affect r* and show a range of estimates for the potential quantitative impact.

Demographics both in the U.S. and across many countries are changing, as falling birth rates, longer life expectancy, immigration and other related factors alter age distributions. Such changes could have significant impacts on national and global economies. In this article, we'll focus on how demographic changes may influence interest rates.

Of particular interest is the effect on r*, or the so-called "natural interest rate." This rate is seen as a key not only in determining the stance of near-term monetary policy but also in thinking more broadly about the longer-term monetary policy framework. As such, it is important for economists and policymakers to understand the economic mechanisms through which demographics could affect r* and have a quantitative sense of the possible effects.

What Is r* and How Is It Determined?

R* can be defined as the long-run real interest rate that would emerge in the absence of disturbances in the economy. It provides a benchmark for policymakers to know how tight or loose monetary policy is at a given point of time.

An interest rate can be viewed as simply a price for capital and savings, just as wages are a price for labor. Interest rates are thus determined by supply and demand factors: The higher the supply of savings and lower the demand for capital, the lower the interest rate will be. Since r* is an interest rate, we can view it through the lens of these forces.

Demographics affect the supply of savings through two channels:

- Households' expectations about their future, including when they will retire and how much longer they might live

- Changes in saving behavior as households move through their life cycle

As a result, the total supply of savings depends on the age composition in the economy.

The demand for capital — driven by how much firms want to invest — also depends on demographics. Workers decide how much to work based on their current circumstances and what they expect in the future. For instance, a worker would be able to work longer and more productive hours when in good health and would want to work more to save up in anticipation of a long retirement.

When either supply or demand forces cause interest rates to fall, households desire fewer savings, and firms are incentivized to borrow and invest more. These responses place further downward pressure on interest rates, amplifying the initial effects of supply and demand.

Quantifying How Demographics Influence r*

Since r* is unobserved, we require a model to study how it might be affected by demographics. Prominent examples include the Richmond Fed's Lubik-Matthes r* and the New York Fed's Holston-Laubach-Williams r* models.

Here, we use an economic model discussed in my paper "Estimating the Effects of Demographics on Interest Rates: A Robust Bayesian Perspective," which explicitly incorporates demographic factors that are not included in the Lubik-Matthes or Holston-Laubach-Williams approaches. Given a set of parameter values, we obtain the implied interest rate from the model, which we interpret as r*. The model captures how demographics influence the interest rate in the economy through the supply and demand forces mentioned above.

To quantify the effect of demographics on r*, we compute how the interest rate in the model shifts with changes in demographic factors. The parameter values one chooses for the model determine how strong the various forces in the model are. While we choose parameters consistent with U.S. macroeconomic and demographic data, there is also substantial disagreement about the appropriate values for these parameters. We report results from a range of different parameter values — taken from various papers that have used similar models — to provide a sense of the uncertainty of our estimates. These parameters involve different levels of trade-off between consumption and saving that households are willing to make (influencing their savings behavior) as well as different speeds of capital depreciation (impacting how much firms invest).

Population Growth

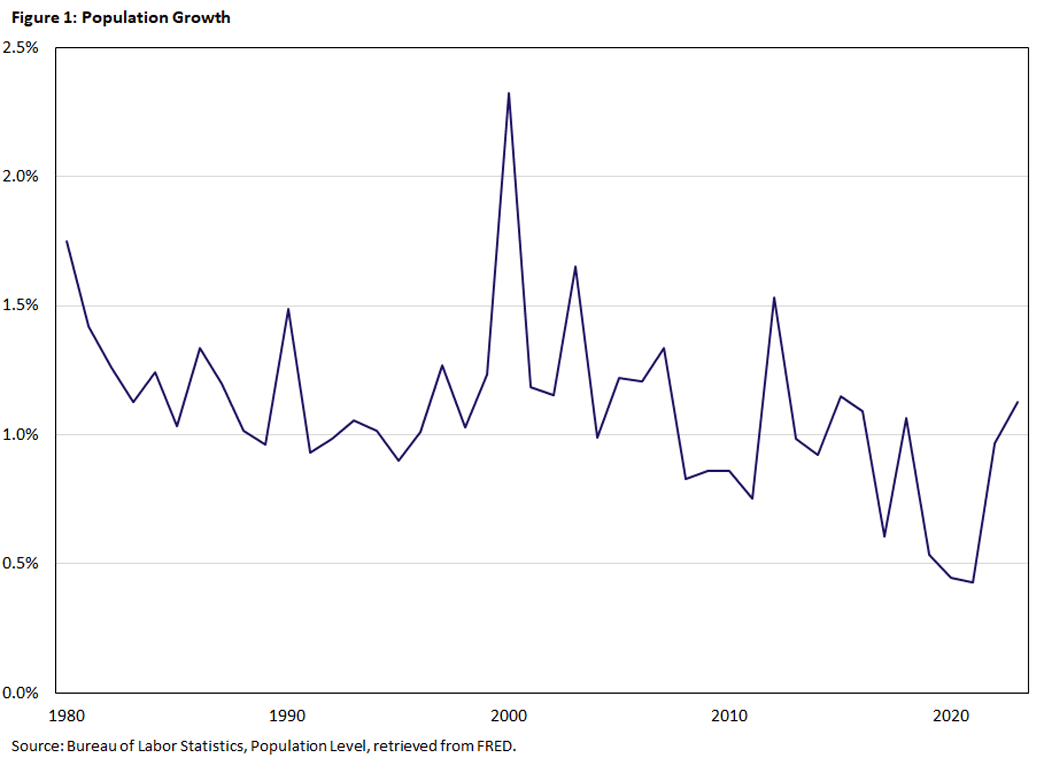

One area we examine that has undergone significant change over the past few decades is population growth, as factors have affected growth in multiple directions. A negative drag on population growth has been the falling birth rate: The birth rate in the U.S. has fallen from 24 births per 1,000 people in 1960 to just 11 per 1,000 people in 2021, and this decline mirrors much of the developed world. A positive note for population growth comes from a 2024 Congressional Budget Office report indicating that immigration may be greater than previously estimated, providing a driver for continued growth in the working population. Figure 1 shows the overall trend in U.S. population growth since 1980.

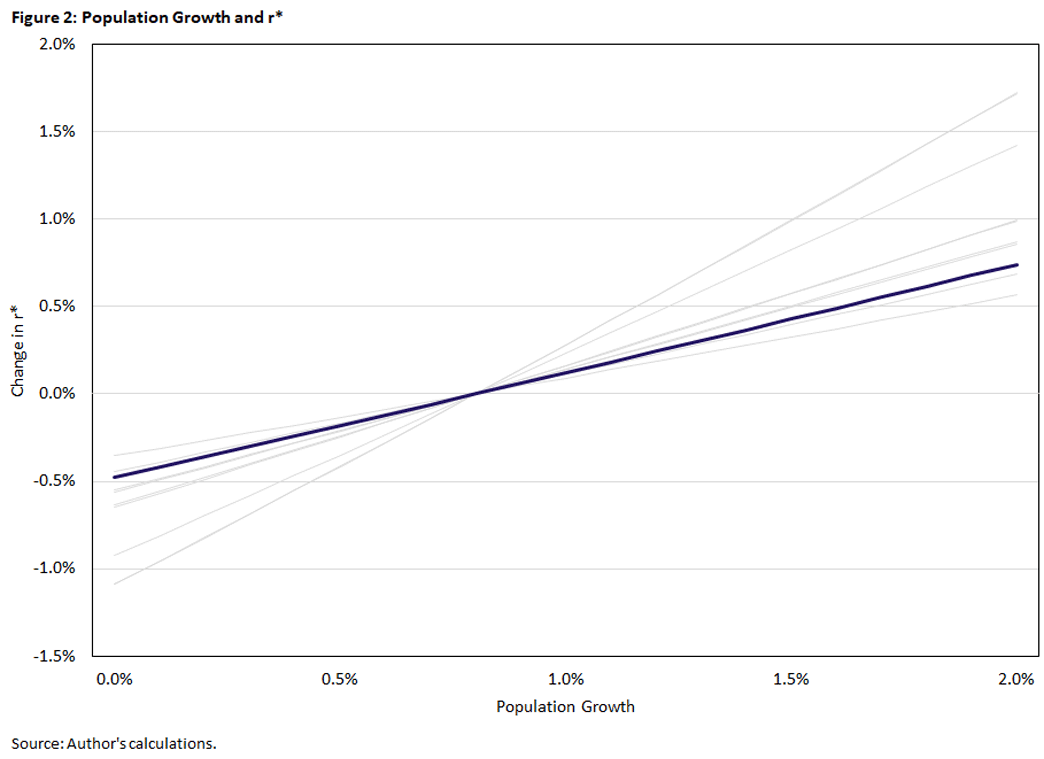

A natural question for policymakers is how such changes might affect r*. Figure 2 shows that r* increases with population growth. However, the parameter values are important for the quantitative effect. In response to a 1 percentage point increase in population growth, our benchmark parameterization (the purple line) predicts an increase in r* of about 0.6 percentage points, whereas the various parameterizations (the gray lines) suggest an increase of anywhere between 0.4 to 1.2 percentage points.

Theoretically, there are forces pushing interest rates in both directions when population growth increases. For instance, young households in the economy tend to save more, thus increasing the supply of savings and putting downward pressure on interest rates.

However, high population growth increases the demand for capital and thus interest rates through two channels:

- Younger workers are more productive, thus increasing the returns from capital.

- The expectation of a growing population leads firms to invest in more capital in anticipation of a larger workforce to utilize this capital for production.

Our quantitative results show that the demand side forces tend to dominate.

Life Expectancy

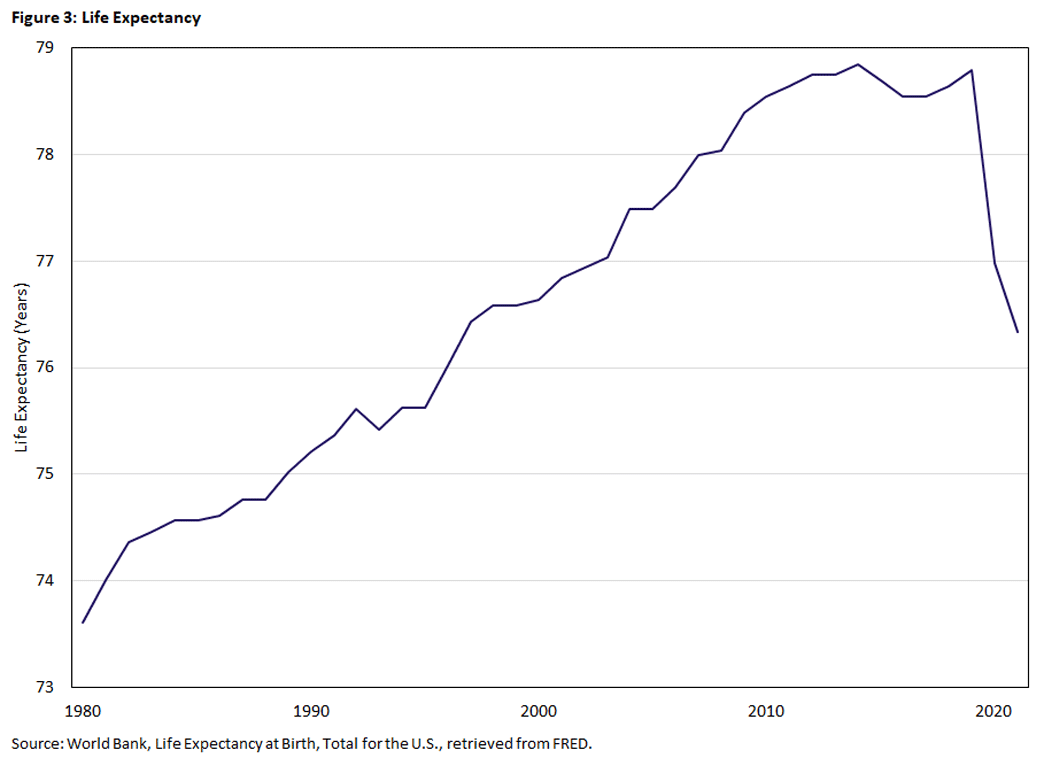

As seen in Figure 3, life expectancy in the U.S. increased from less than 74 years in 1980 to almost 79 years in 2019, before declining following the onset of the pandemic. A similar increase in life expectancy has also been seen globally, notably in countries such as Japan.

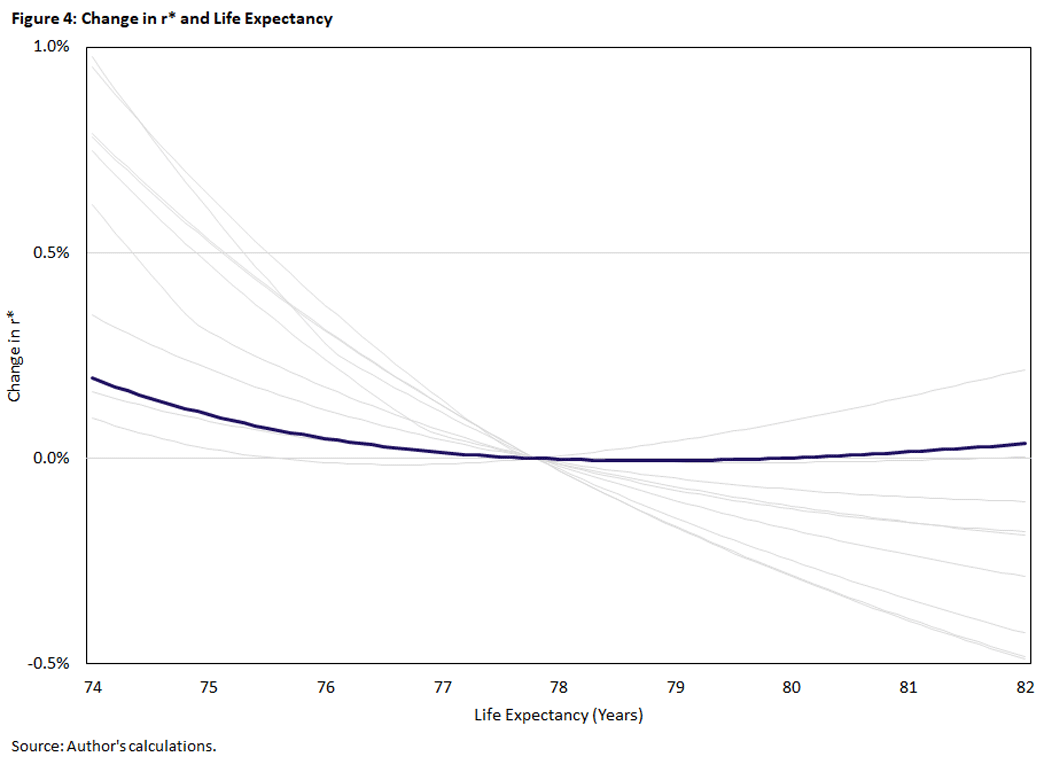

Figure 4 shows that the impact of these changes in life expectancy on interest rates is ambiguous both qualitatively and quantitatively. In our baseline (the purple line), increasing life expectancy corresponds to a decline in r* for shorter life expectancies but a slight increase for longer life expectancies. Under other scenarios (the gray lines), most parameterizations generate a decrease in r* with longer life expectancy, but we show that there are some parameter values for which the opposite is true, at least for certain empirically relevant lengths of life expectancy.

The range of results once again reflect a range of economic effects in the model potentially working in different directions. The supply of savings increases as households save more in anticipation of a longer period of retirement, driving down the interest rate.

The effect on the demand for capital is less clear. While the longer life expectancy increases labor supply overall, the higher fraction of old workers in the economy reduces the average productivity of a worker. As indicated by the range of estimates, the relative strength of these forces depends on the choice of parameters for the model.

Conclusion

The model calculations suggest that decreases in population growth and increases in life expectancy would tend to decrease r*, although there is substantial uncertainty about the magnitude of this decrease. In the case of life expectancy, alternative parameter values could even reverse the result.

The fact that multiple supply and demand forces are in play simultaneously and are potentially working in opposite directions is a consideration for a broader range of long-run changes in demographic and economic factors of interest. Quantitative models are necessary for policymakers to disentangle and weigh these different effects.

Nevertheless, one should acknowledge the uncertainty in the estimates given not only the parameter uncertainty that we focus on here, but also the fact that our models are only approximations and not exact replications of reality.

Paul Ho is an economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Ho, Paul. (June 2024) "How Do Demographics Influence r*?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 24-18.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.