The 2021 Rise in U.S. Inflation: A Cross-Country Perspective

U.S. inflation started to rise dramatically in the spring of 2021 and has remained high. While there has been substantial month-to-month volatility, higher price increases have been pervasive across consumption categories since late 2021.

This isn't occurring only in the United States. Inflation has reared its ugly head in most other advanced economies as well. What can we learn from their experiences? In this blog post, we look at patterns across several countries to get insight into potential sources of high inflation in the United States.

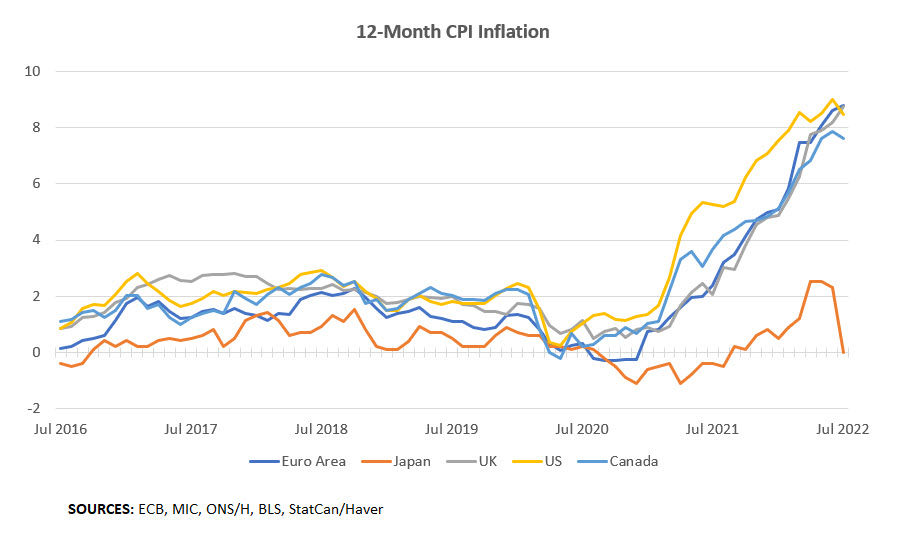

"During 2021, inflation rose and eventually was far above its pre-COVID-19 average in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom and Canada. Inflation also rose in Japan, but the increase relative to pre-COVID-19 levels was much less than in the other regions."

Broadly speaking, inflation is determined by the interaction between monetary policy and a wide range of other factors. However, identifying specific causes is challenging, especially in real time. In the current situation, inflation patterns across countries can be informative. We consequently argue that these patterns are consistent with monetary policy being an important source of the high inflation.

Figure 1 below plots data on year-over-year inflation for the United States, the Euro Area, the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan.

Two features jump out from the figure:

- During 2021, inflation rose and eventually was far above its pre-COVID-19 average in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom and Canada.

- Inflation also rose in Japan, but the increase relative to pre-COVID-19 levels was much less than in the other regions.

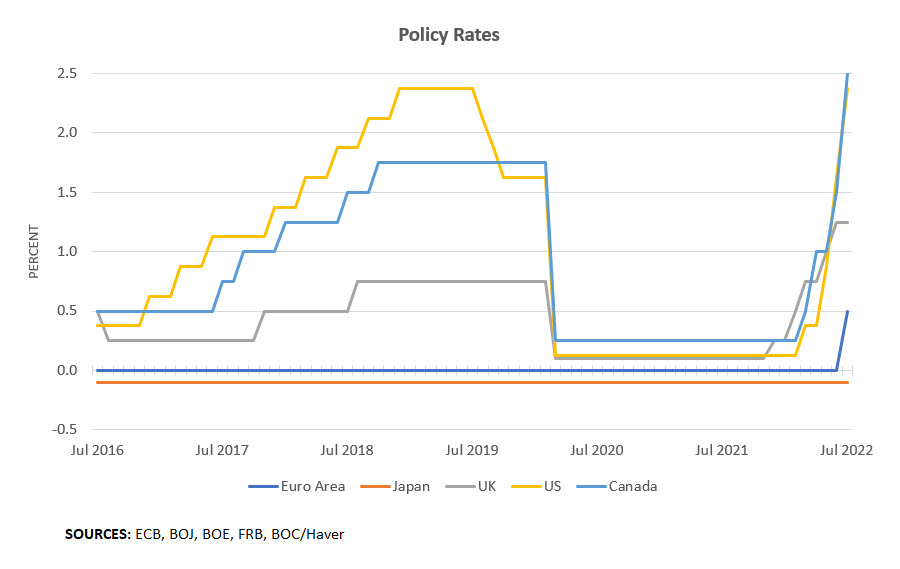

Unusual conditions affecting the supply and demand for particular categories of consumption have undoubtedly played a role in the recent behavior of U.S. inflation. However, the pervasive and persistent nature of inflation in the United States suggests monetary policy may have also been a key factor. Figure 2 below plots the monetary policy interest rate instruments for the same five regions.

At the onset of COVID-19, the three central banks that had interest rates away from their lower bound — the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England — rapidly lowered them to zero. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan maintained negative policy rates. The key observation is that for all five central banks, the policy interest rate was at its (effective) lower bound during the period when inflation rose dramatically.

At the same time, Figure 2 may first appear to be inconsistent with monetary policy as a source of the high inflation: All five central banks kept their policy rates low, yet inflation stayed low in Japan while rising elsewhere.

This reasoning relies on the policy rate being a good measure of the stance of monetary policy. However, according to the modern theory of monetary policy (see, for example, the 1997 paper "The New Neoclassical Synthesis and the Role of Monetary Policy" and the 2003 book Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy), the stance of monetary policy is best represented by the gap between the policy interest rate and the natural rate of interest. The natural rate of interest is unobservable, so it can be challenging to operationalize this approach to policy.

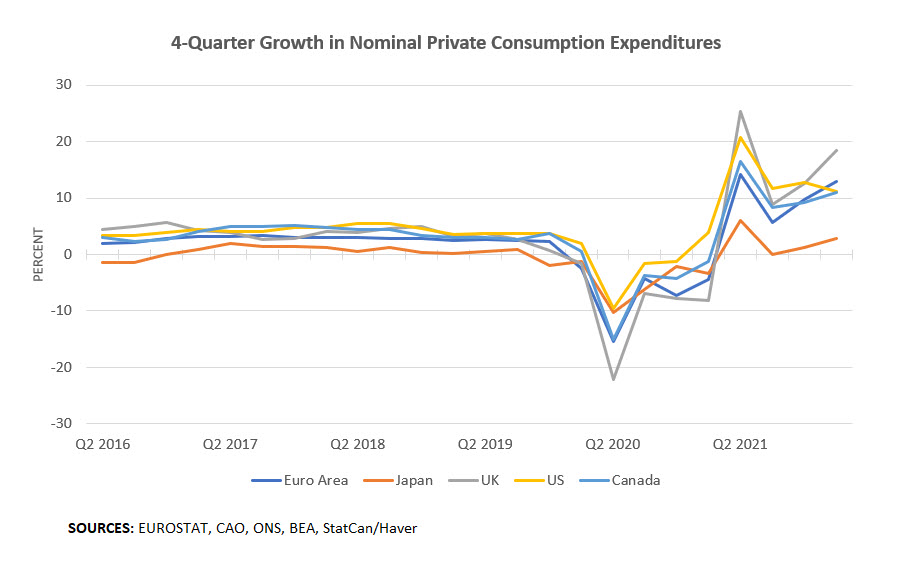

One clue can be found in Figure 3 below, which plots nominal consumption growth in the five regions.

Everywhere except Japan, nominal consumption growth increased in 2021 to far above its pre-pandemic rate. While not definitive, this differential behavior is consistent with monetary policy being an important source of the high inflation outside of Japan.

Even though each central bank's policy rate stayed at the lower bound until late 2021, the high consumption growth outside of Japan suggests that the gap between the policy rate and the natural rate was lower (more negative) outside of Japan. The question of why the natural rate might have behaved differently in Japan is an important one, but we leave that for another post.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.