Are Supersized Wage Increases Over?

Wage inflation appears to be showing signs of slowing. January's payroll employment data revealed that average hourly earnings (AHE) for production and nonsupervisory workers rose 0.3 percent monthly, following a 0.4 percent increase in December and a 0.5 percent increase in November.

These increases, however, aren't distributed evenly across sectors. Some workers may continue to see larger than normal pay increases as wage differentials across sectors revert to their pre-pandemic norms. In this post, we'll examine one potential industry: the construction industry.

The inspiration for this week's post comes from Ken Simonson, chief economist of the Associated General Contractors of America and a member of the Richmond Fed's Industry Roundtable. Simonson noted that AHE for production and nonsupervisory workers in the construction industry typically runs 20 percent to 25 percent higher than the national average, as workers in the construction industry earn a premium for performing skilled and manual-intensive labor.

In the worst of the pandemic shock, that construction wage premium fell to around 14 percent as wages in other industries, such as leisure and hospitality, began rising rapidly relative to construction wages. During a recent Richmond Fed Industry Roundtable, Simonson suggested that further adjustment in construction wages is likely as the construction wage premium is restored.

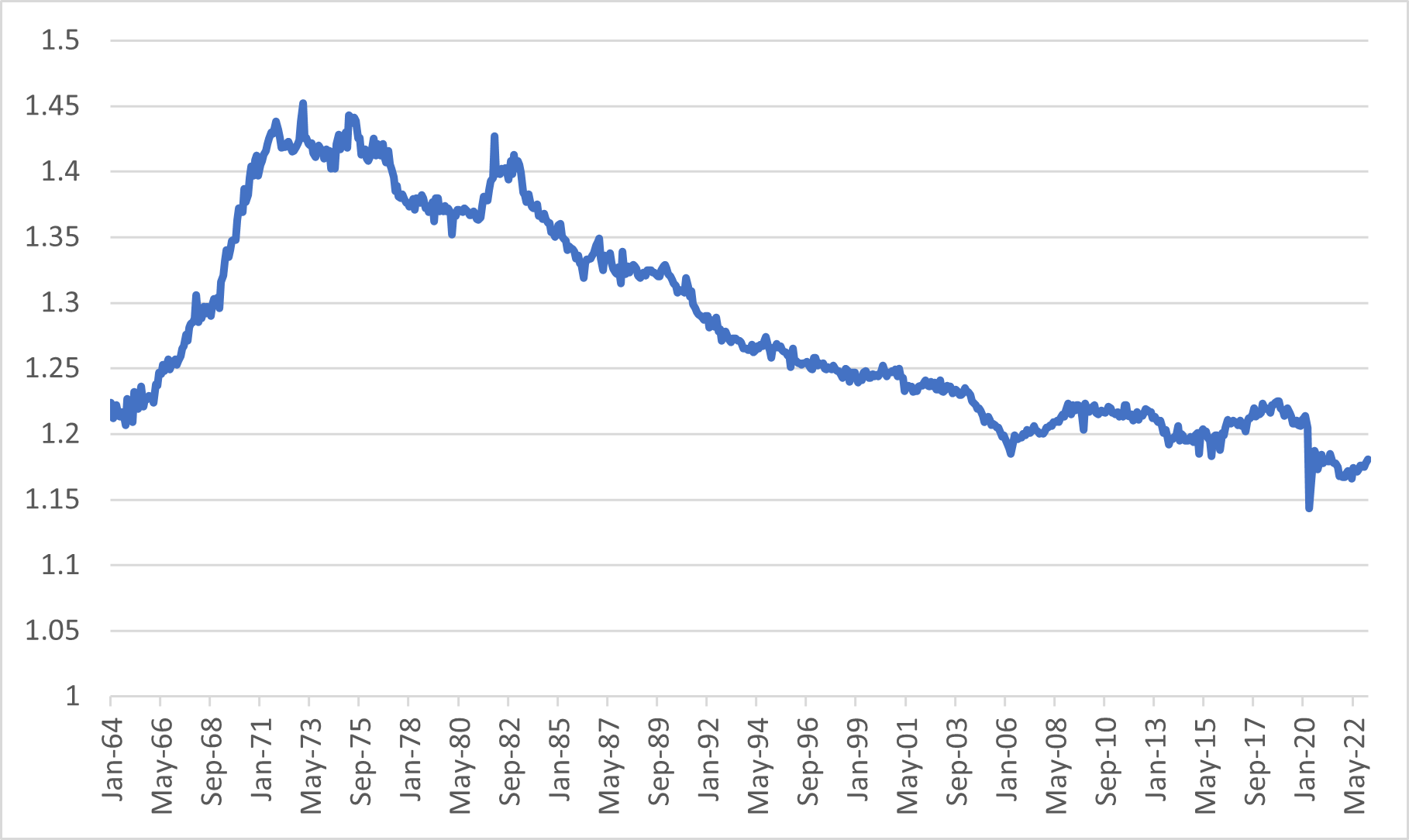

But just how likely is this adjustment? To help see this from multiple perspectives, Figure 1 below plots the ratio of AHE for production and nonsupervisory workers in construction to those for the total private sector from 1964 to the present.

Viewed from a longer historical perspective, AHE in construction has trended downward since the 1970s. However, in the 15 years before the pandemic, that ratio had seemingly settled at construction wages being 20 percent higher than the private sector average. So, depending on how long of a history you consider, the decline in the construction AHE wage premium during the pandemic could be seen as either the continuation of a decadeslong trend or a sudden drop after a 15-year period of relative stability.

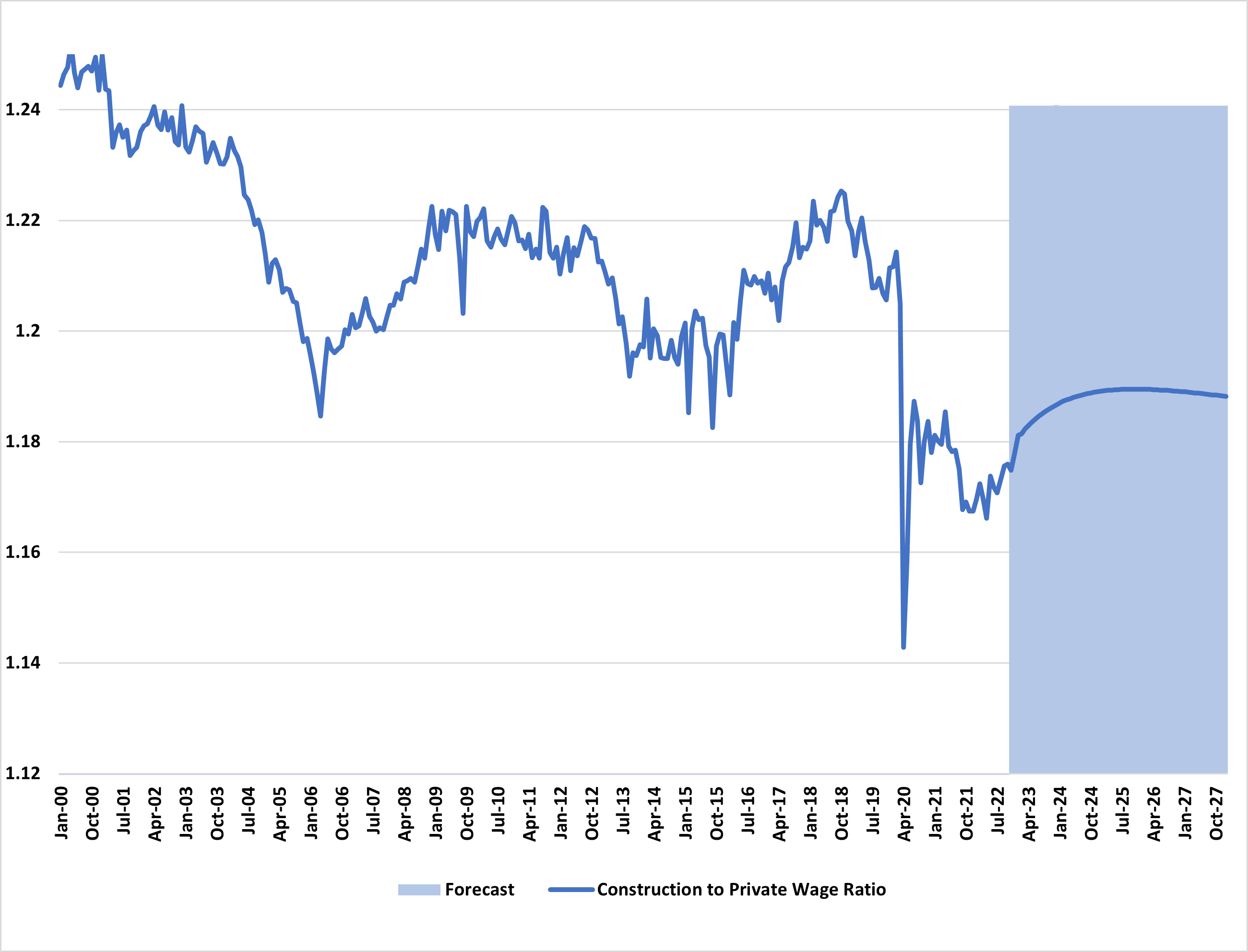

To see which view might pan out, we used a statistical technique that models the long-run relationship between variables (AHE in construction versus the total private sector) and describes how short-run deviations (changes in the construction wage premium) are corrected. (Note: We used this procedure in another post to model the relationship between the consumer price index and producer price index.)

Importantly, we ran this model on historical data starting in 2000, corresponding to the time when the construction wage premium was in the range of 20 percent to 25 percent over the private sector average. The shorter sample means that the model's predictions don't take into account the long-run decline starting in the 1970s and skew in favor of the wage premium normalizing to pre-pandemic levels.

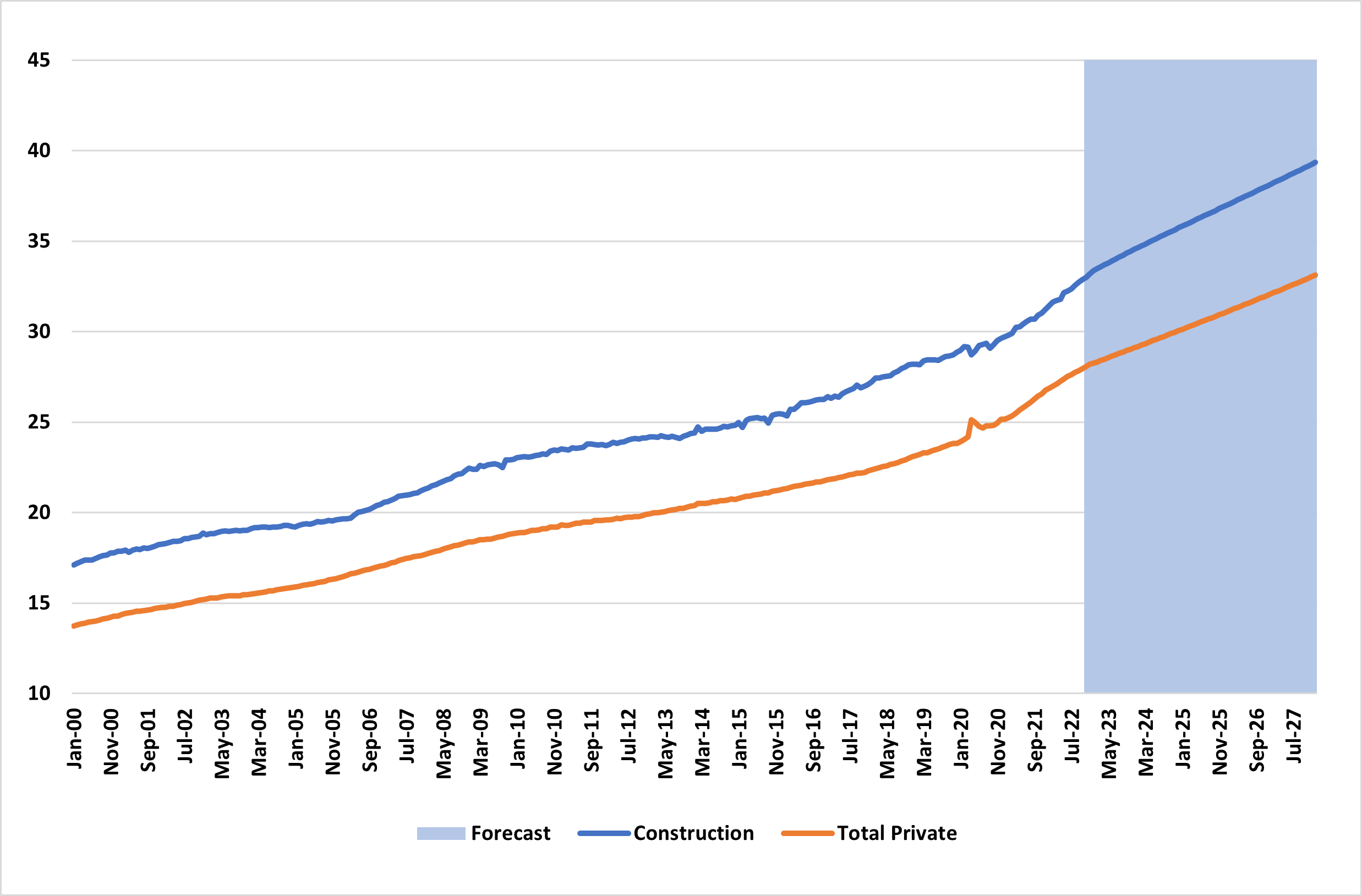

However, even after skewing the results in favor of recent history, the model predicts that, while the construction wage premium will rise further, it doesn't fully return to its pre-pandemic levels. Figure 2 below shows the model's forecast for AHE in the construction industry and in the total private sector.

Figure 3 below computes the ratio of the two series. Assuming both series rise in line with their historical patterns since 2000, the model projects that the construction wage premium will widen again but not to the pre-pandemic level. It estimates that the premium will rise from 18 percent today to only 19 percent in 2025.

For construction workers at least, the days of outsized wage increases may not be over quite yet. According to the model, construction wages could outpace the overall average in the short run as the construction wage premium partially recovers toward its pre-pandemic level.

But many factors could complicate how wages actually unfold: This simple model ignores important factors like today's historically low unemployment rate of 3.4 percent — which points to a tight labor market that could keep wage growth higher for longer — as well as borrowing rates which are higher today than before the pandemic, in turn increasing costs and lowering activity in the interest rate-sensitive construction industry.

Note to readers: The blog will go on hiatus the week of February 20 due to the Presidents Day holiday and will resume on February 28. Have a great long weekend!Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.