Sizing Up Spending in a Shutdown Scenario

Last weekend, policymakers avoided a potential federal government shutdown which would have suspended nonessential government services, including those provided by statistical agencies such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. If a deal had not been struck, the release of some important data series could have been postponed, including job openings and quits (Oct. 3), durable goods orders (Oct. 4), September payroll employment and unemployment (Oct. 6), vehicle sales (Oct 6.), producer prices (Oct. 11), CPI (Oct. 12) and third-quarter GDP (Oct 26). In this week's post, we explore alternative series that might have been used to measure the strength of consumer demand in the absence of official measures of personal consumption expenditure (PCE).

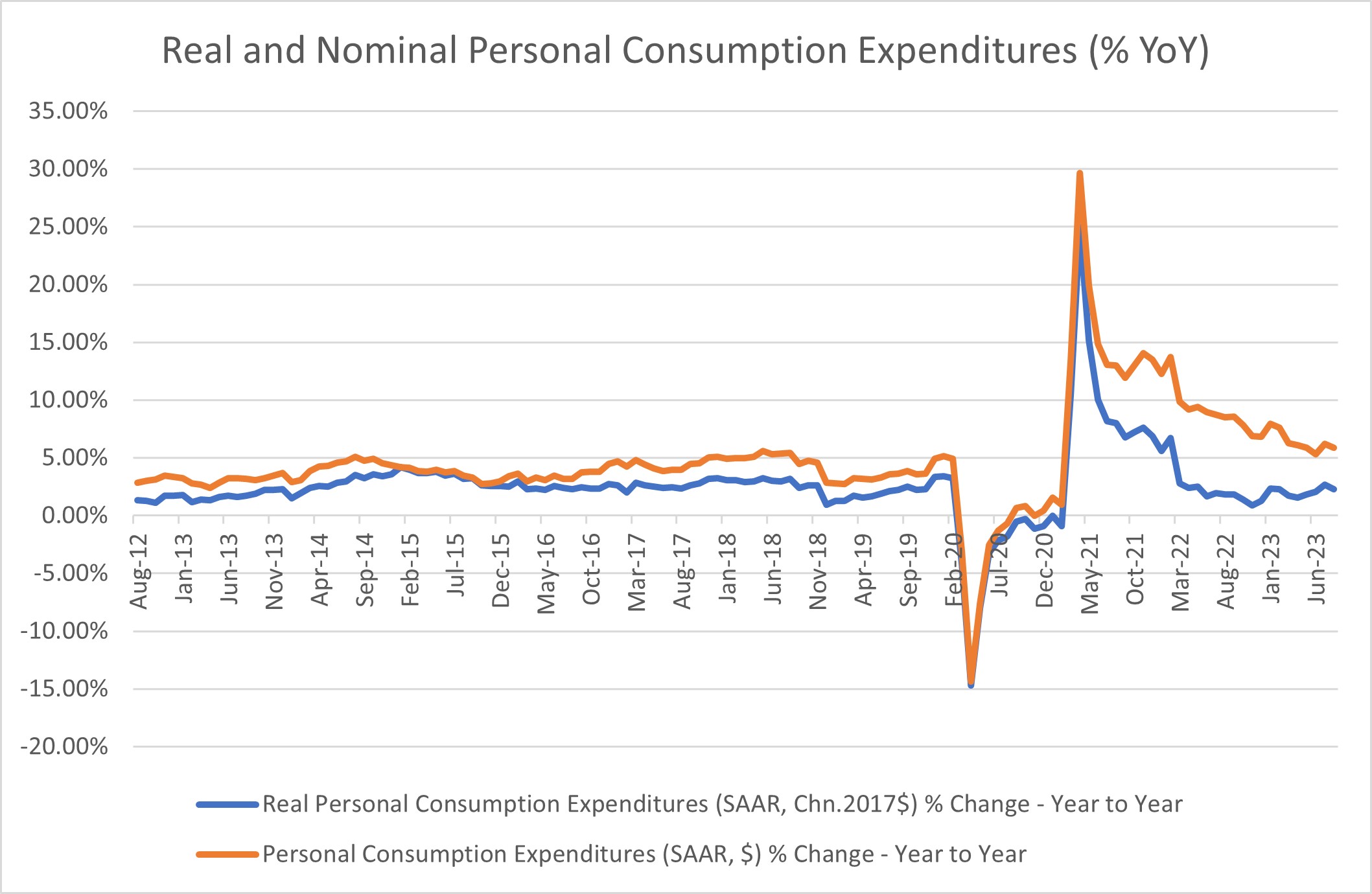

Before dipping into unofficial measures of household demand, it's useful to take stock of what official, government-produced measures are saying about the strength of consumer spending. Figure 1 below shows year-over-year growth in nominal and real personal consumption expenditures. As of August, year-over-year PCE growth has been positive this year, at 5.9 percent in nominal terms and 2.3 percent after adjusting for inflation. Based on these measures, household spending continues to rise at a healthy clip.

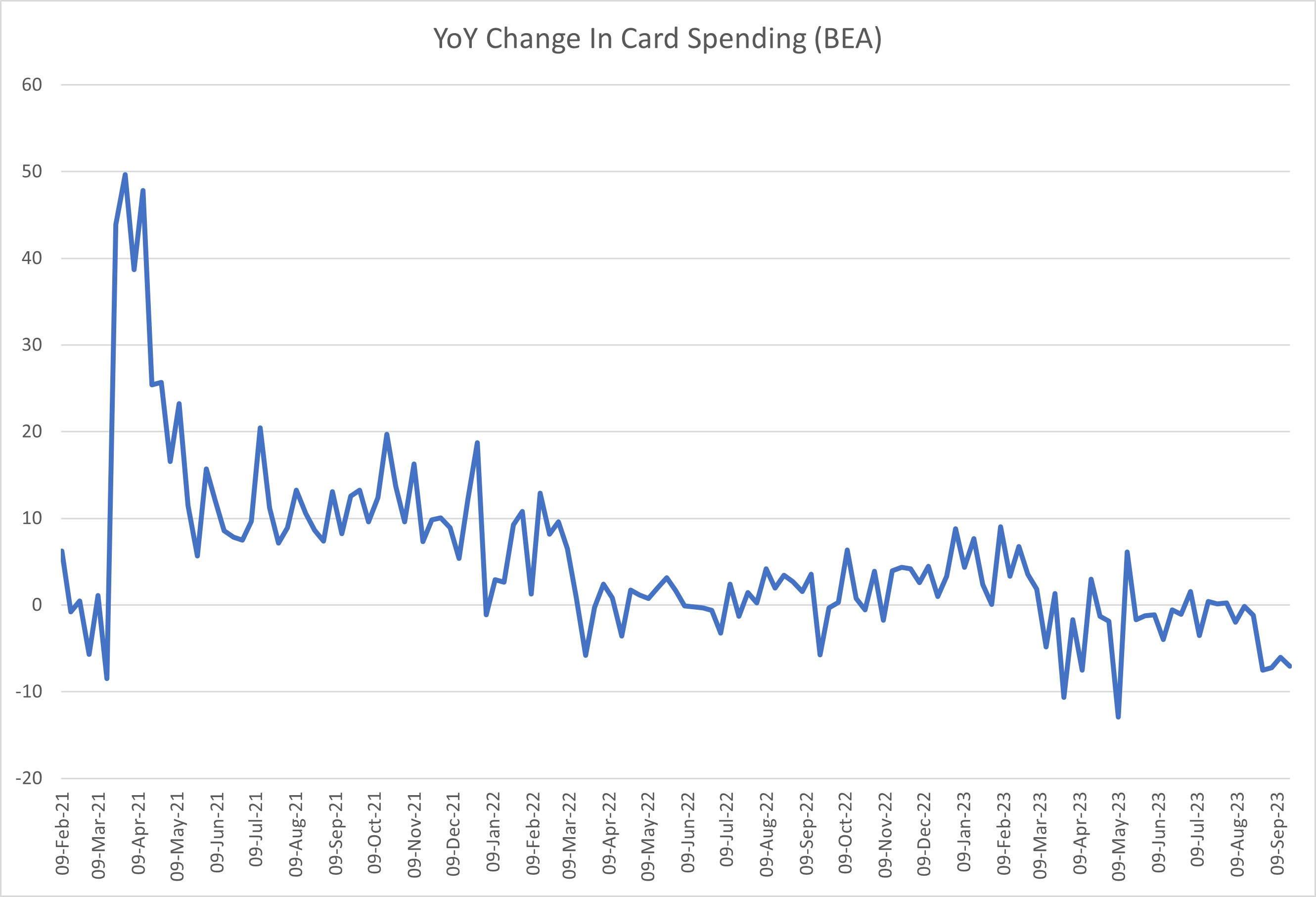

A prolonged government shutdown might have affected the timeliness of this important metric of household demand. In that scenario, policymakers could use alternative measures of spending — such as high-frequency card spending data (which we discussed in the post "Spend as I Do, Not as I Say") — to gauge consumer momentum. Although Figure 2 below shows a BEA-produced measure, similar proprietary measures are available from private vendors. Interestingly, in contrast to official PCE, the year-over-year growth in credit and debit card spending has been negative this year, suggesting weaker spending versus a year ago.

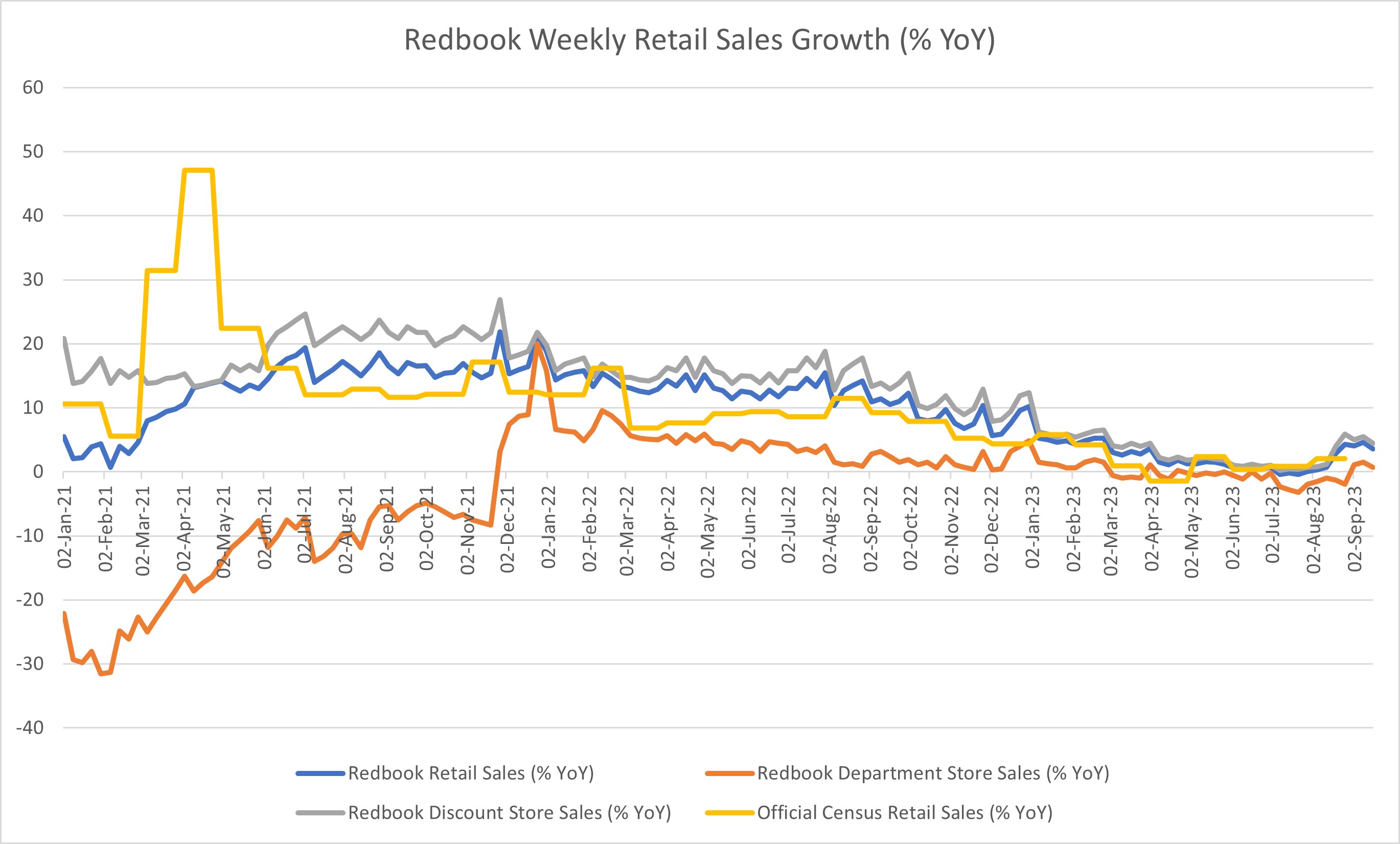

Another high-frequency measure of consumer spending is the weekly Johnson Redbook Retail Sales Index, which tracks same-store sales of a sample of large U.S. general merchandise retailers. The data are broken out into sales at department stores versus discount stores, providing an additional degree of insight into the composition of retail spending.

The latest reading suggests retail sales growth has remained in modestly positive year-over-year territory over the past six weeks, as seen in Figure 3 below. However, that growth is largely attributable to a pickup in spending at discount stores. In contrast, department store sales have been roughly flat year over year.

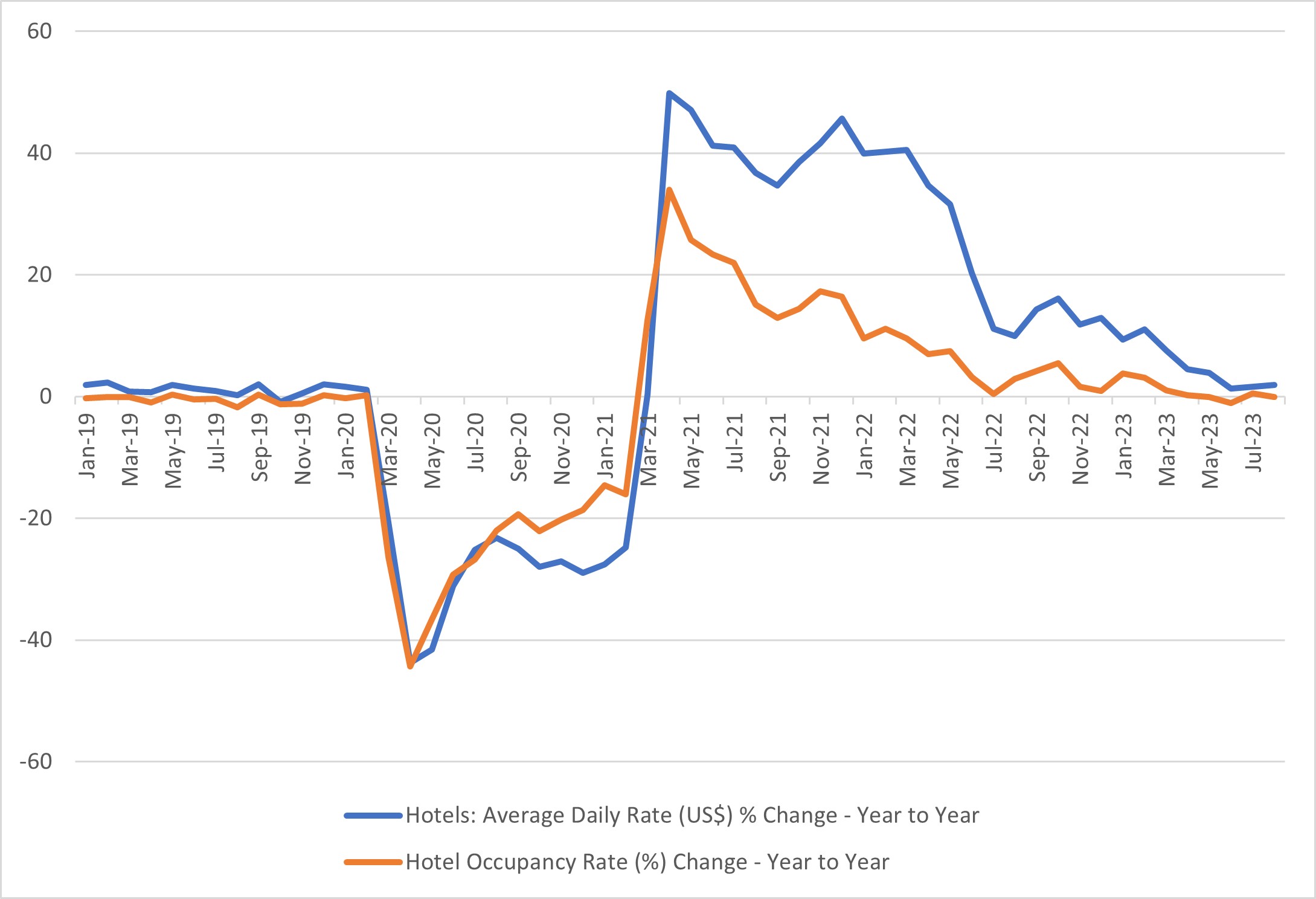

Other data provide insights from individual sectors, including weekly restaurant demand measured as year-over-year change in seated diners via OpenTable (with the index being negative since mid-July), as well as monthly average hotel rates and occupancy from Smith Travel Research, or STR. Hotel data are plotted in Figure 4 below, illustrating that hotel occupancy rates are now roughly flat on a year-over-year basis and that growth in average daily rates has fallen below 2 percent year-over-year.

Interestingly, the high-frequency and alternative measures examined in this post seem to be pointing toward a steeper slowdown in spending compared to the official PCE measure: The nonofficial indexes seem to indicate that spending is either flat or shrinking, or they may be suggesting that households are becoming thriftier in their shopping.

In the fog of a shutdown scenario, economy-watchers might downgrade their assessment of current economic growth not only because of the direct impact of the shutdown itself, but also because the only measures of economic activity they would have available are painting a more pessimistic picture of the trajectory of demand.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.