Labor Productivity Is Popping

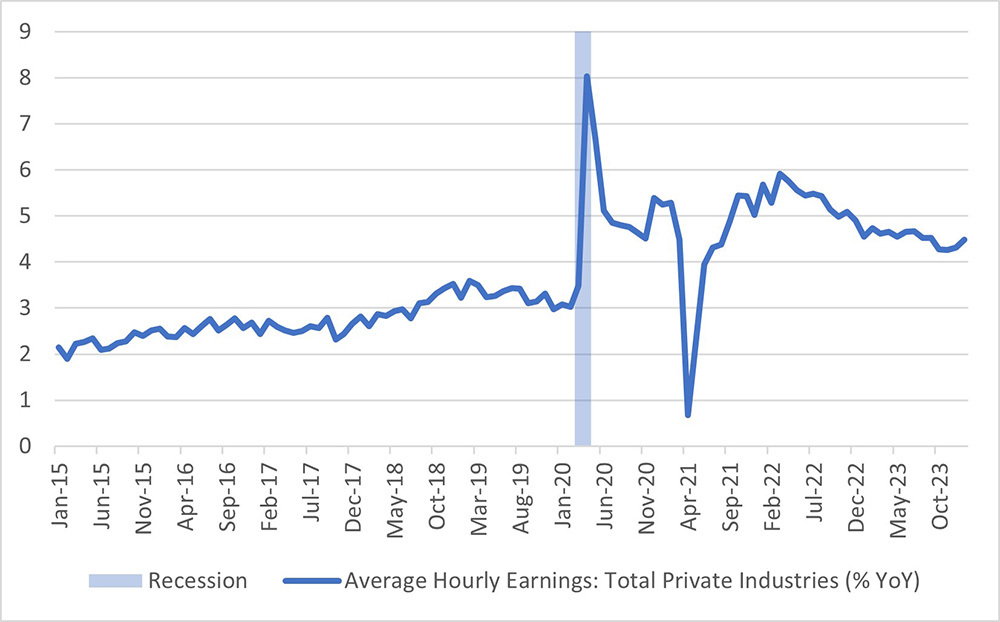

January's jobs report featured robust growth of 353,000 nonfarm payroll jobs — an upward revision to December's jobs growth of 333,000 from an initial reading of 216,000 — and the unemployment rate remaining at a low 3.7 percent for the third straight month. Wage growth was also strong: Average hourly earnings in the private sector are up 4.5 percent year over year — compared to 4.3 percent in November — with growth rates remaining above the pre-pandemic pace. (See Figure 1 below.) How can strong wage growth coexist with encouraging signs that recent inflation readings have remained at the Fed's target? The key link is labor productivity.

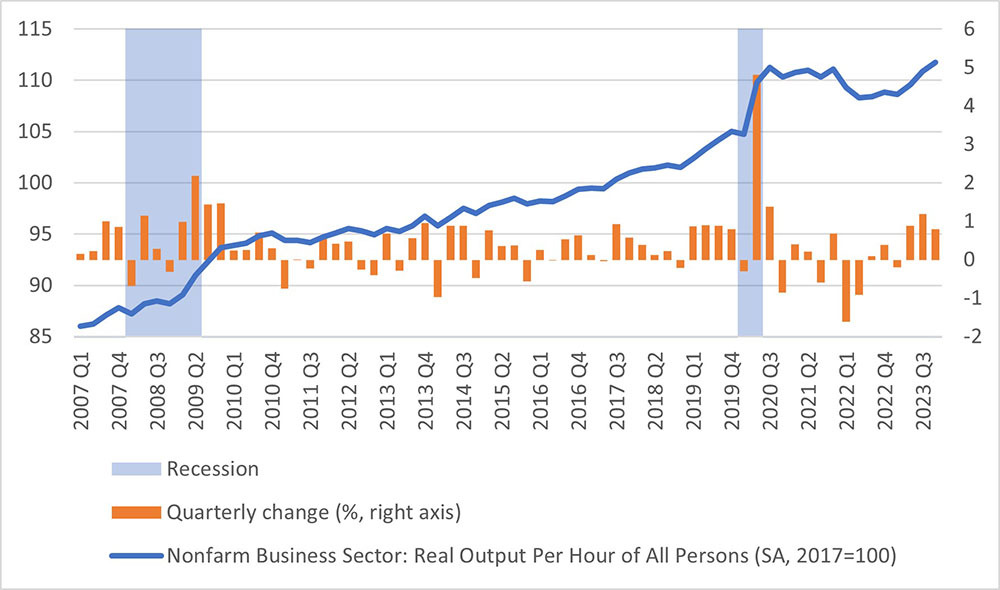

Labor productivity (measured as output per hour worked) rose 0.8 percent quarter over quarter in the fourth quarter and is up 2.7 percent year over year, as seen in Figure 2 below. This growth in productivity has been robust compared to recent history. In the decade before the pandemic (2010-2019), productivity rose at average paces of 0.3 percent quarter over quarter and 1.3 percent year over year. Figure 2 also shows that productivity growth is volatile and can swing from positive to negative even in nonrecessionary quarters. Nevertheless, the past three quarters have seen robust productivity growth.

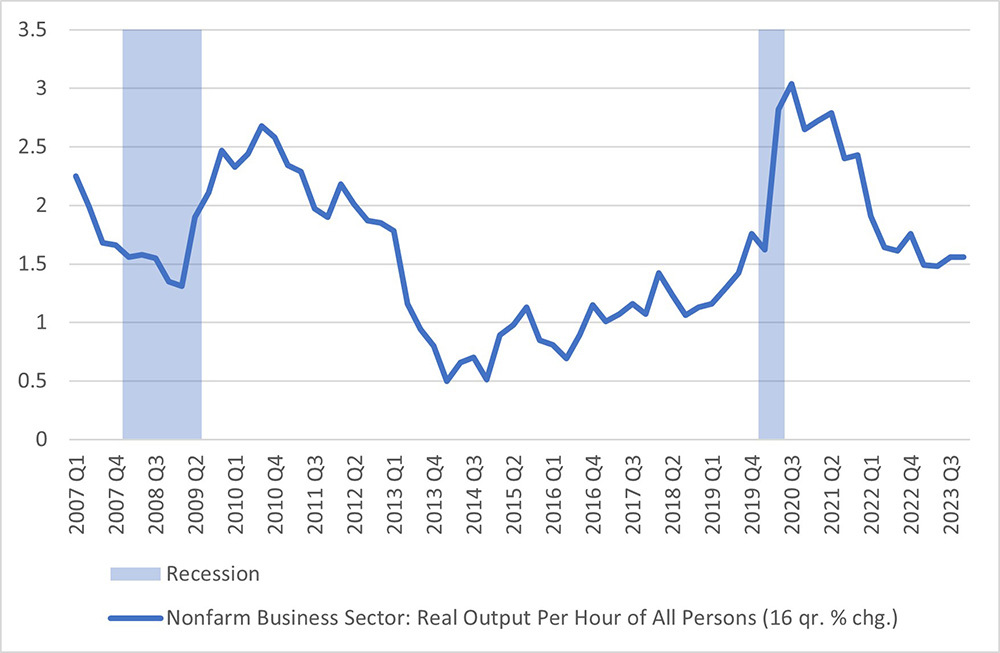

One way to smooth volatility in the quarterly growth numbers is to examine changes over longer time horizons. Figure 3 below looks at four-year annualized growth of labor productivity, a window which compares all COVID-19 era observations against a pre-COVID-19, nonrecessionary baseline. As of the fourth quarter of 2023, four-year annualized growth of labor productivity was 1.6 percent — the same as in the third quarter — and remains in the upper end of its recent (2015-2019) pre-pandemic range.

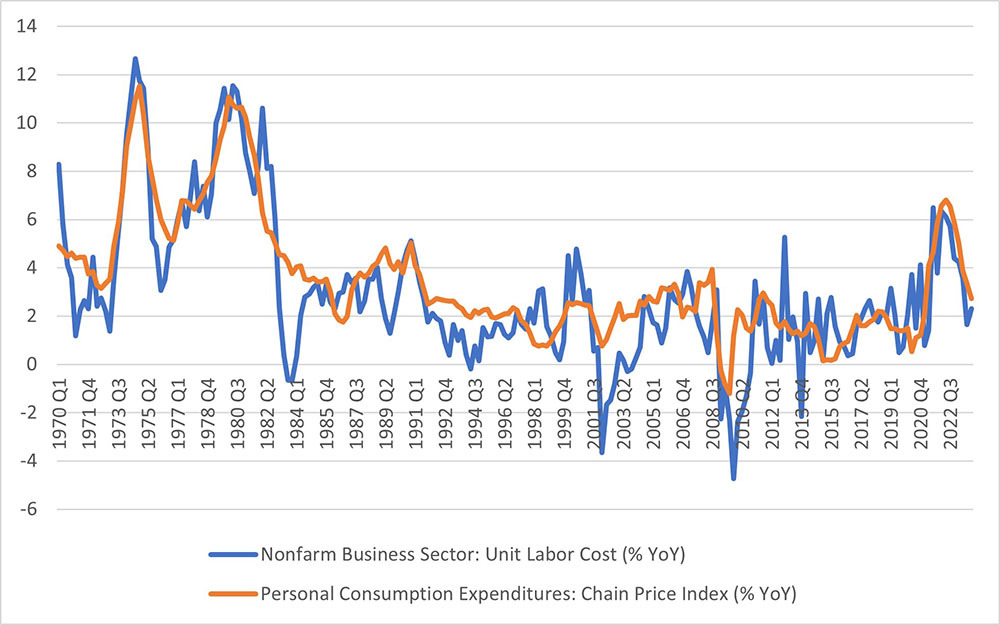

Strong productivity gains have dampened the inflationary impulse of ongoing strong wage growth in recent inflation readings. Figure 4 below shows growth in unit labor cost, which represents the productivity-adjusted wage growth tied to inflation. Unit labor cost rose 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 and is up 2.3 percent from its year-ago reading, with both growth rates within their pre-pandemic ranges. This suggests that, after adjusting for productivity, wage gains have not contributed to above-target inflationary pressure in recent months.

Still, given the historic volatility in quarterly productivity growth, whether the current string of outsized productivity gains can be sustained will be an important question about the inflation outlook in coming months. If productivity gains slow while wage growth remains elevated, questions about labor market pressures on inflation could once again reemerge.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.