Help Wanted

Employers are having a hard time hiring. Not enough workers or not the right skills?

Before every meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed publishes a new Beige Book, a compilation of qualitative economic information from each Federal Reserve district. In the most recent one, the Richmond Fed's business contacts reported that "labor demand strengthened and job openings increased as employers struggled to find qualified workers." The language would have been familiar to regular readers: Six years earlier, the Beige Book had noted that "[Fifth] District employment improved somewhat, but both manufacturers and professional services firms continued to report problems finding qualified workers."

It's not surprising that employers are having a hard time finding workers today, when the unemployment rate is the lowest it's been in nearly five decades. But why were they having trouble finding workers in 2012, when the unemployment rate had been stuck above 8 percent for several years?

Many people attributed persistently high unemployment after the Great Recession to "skill mismatch" — the idea that the people looking for work didn't have the qualifications employers were seeking — and there was considerable concern that such mismatch would be a permanent feature of the labor market. Today, however, things look quite different: Many lower-skill occupations, once the hardest hit, are now in high demand, and employers are increasingly willing to train. Is skill mismatch a thing of the past?

It's Getting Hot, Hot, Hot

In September 2018, the unemployment rate dropped to 3.7 percent — its lowest reading since December 1969. At the same time, the Congressional Budget's Office estimate of the "natural" rate of unemployment, which is widely viewed as the benchmark for full employment, was 4.6 percent. (Even in a healthy economy, there will always be some level of unemployment as workers transition between jobs. The natural rate is the lowest rate that can be maintained without accelerating inflation.)

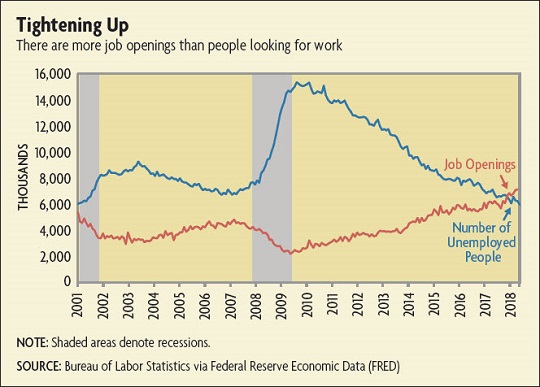

That's not the only indication the labor market is tight. In 2000, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) began tracking data on labor market turnover, including job openings. In April of this year, for the first time ever, there were more vacancies than there were people looking for work, and the gap has continued to grow. (See chart below.)

"Global Dynamics in a Search and Matching Model of the Labor Market," Working Paper No. 17-12, October 2017.

"Measuring Resource Utilization in the Labor Market," Economic Quarterly, First Quarter 2014.

"Accounting for Unemployment in the Great Recession: Nonparticipation Matters," Working Paper No. 12-04, June 2012.

Labor market tightness isn't evenly distributed across industries, however. The job openings rate for accommodation and food service workers was 6 percent in August 2018, for example, while the rate for educational services was just 3.2 percent. Economists at ZipRecruiter, an online recruitment firm, analyzed responses to job postings and found 118 applicants for every administrative position advertised but just 12 responses per truck driving job and nine per nursing job. Even within industries there is variation; in the Census Bureau's Quarterly Survey of Plant Capacity Utilization, just 3.5 percent of textile manufacturers reported an "insufficient supply of labor" as a constraint in the second quarter of 2018. But 32 percent of wood manufacturers were constrained by their inability to find workers.

There are geographic differences as well. Across Virginia as a whole, the unemployment rate has averaged 3.1 percent in 2018, well below the national average. But in some western and southern counties, the rate has been around 6 percent; in many northern counties, it's averaged about 2.5 percent. In North Carolina, average county unemployment rates for 2018 range from 7.7 percent in Scotland County, which has lost several thousand manufacturing jobs over the past two decades, to 3.1 percent in Buncombe County, home to tourist destination Asheville.

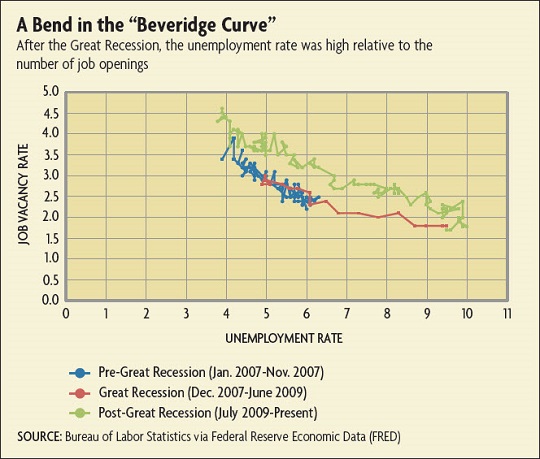

Baffled by Beveridge

Still, 7.7 percent unemployment is a significant improvement from the end of the Great Recession, when unemployment in Scotland County topped 17 percent. Nationally, the unemployment rate reached 10 percent in October of 2009 and remained above 7 percent until the end of 2013. Historically, high unemployment has been associated with few job openings (because employers aren't interested in hiring) and low unemployment with plentiful job openings, a relationship known as the Beveridge curve. But as the economy began to recover in 2009 and firms started posting jobs, the unemployment rate remained several percentage points higher than the Beveridge curve would have predicted.

The position of the Beveridge curve is determined by how efficiently the labor market pairs available workers with available jobs, what economists call "matching efficiency." Multiple factors influence matching efficiency, including employers' recruiting processes, how people search for jobs, and policies such as unemployment insurance or at-will employment. The rightward shift of the Beveridge curve after 2009 suggested that overall matching efficiency had declined significantly. (See chart below.)

Readings

Barnichon, Regis, and Andrew Figura. "Labor Market Heterogeneity and the Aggregate Matching Function." American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, October 2015, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 222-249. (Article available with subscription.)

Hornstein, Andreas, and Marianna Kudlyak. "How Much Has Job Matching Efficiency Declined?" Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter No. 2017-25, Aug. 28, 2017.

Lubik, Thomas A., and Karl Rhodes. "Putting the Beveridge Curve Back to Work." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief No. 14-09, September 2014.

Şahin, Ayşegül, Joseph Song, Giorgio Topa, and Giovanni L. Violante. "Mismatch Unemployment." American Economic Review, November 2014, vol. 104, no. 11, pp. 3529-3564. (Article available with subscription.)

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.