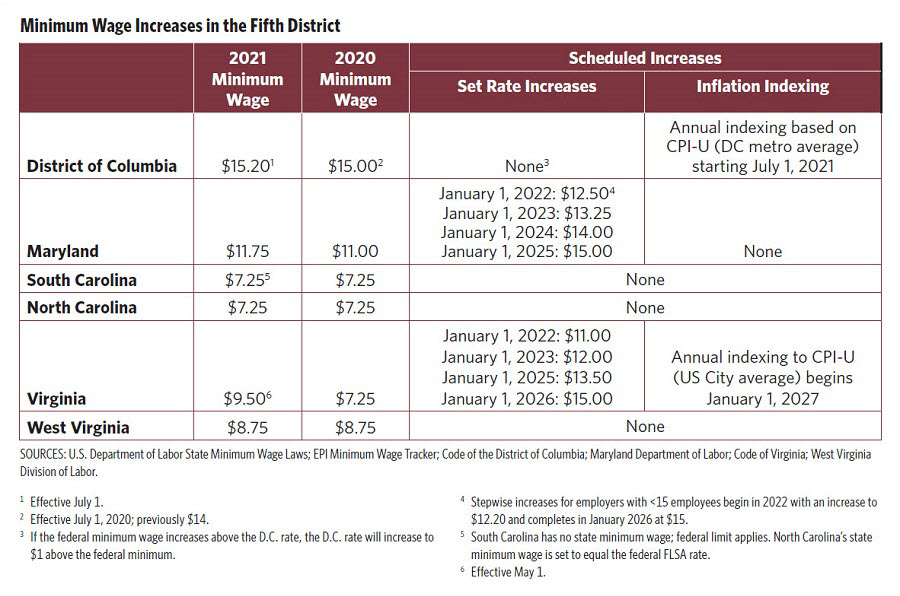

As in federal minimum wage legislation, states can write occupational and industry exceptions, as well as accommodations for very small businesses, into their minimum wage requirements. In some states, localities can set local minimum wage rates that exceed the state and federal minimums. For example, in Maryland, Montgomery County (and until recently, Prince George's County) instituted a minimum wage above both the state and federal minimums. But local minimum wages are more the exception than the rule in the Fifth District: Court rulings and state laws in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina prevent localities from setting their own minimum wage rates. In West Virginia, although no legislation prohibits localities from mandating higher minimum wages, no locality has ever implemented a higher minimum.

There are a number of reasons why states or localities might adopt their own minimum wage. First, the FLSA does not index the minimum wage to inflation. In fact, the buying power of the federal minimum wage peaked in 1968 when it was $1.60, which equates to $11.90 in 2020 dollars. Some states and localities across the country, including in the Fifth District, have indexed minimum wage increases to a consumer price index to account for future price increases. Second, the federal minimum wage does not account for regional variations in the cost of living, which states can address through higher state minimums and by allowing local minimum wage rates above state requirements. Third, setting their own legislation can enable states to fine-tune their minimum wages, for example, by setting separate stepwise increases for small businesses.

Effects of a Minimum Wage Increase

When trying to assess the potential impact of an increased minimum wage, the first step is to understand which workers are likely to be affected. In a 2019 article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Doruk Cengiz of the firm OMP and co-authors estimated employment and wage changes in reaction to 138 state-level minimum wage increases between 1979 and 2016. They found that spillovers in wage increases extend up to $3 above the minimum wage and represent around 40 percent of the overall wage increase from minimum wage changes. (They calculated a 6.8 percent increase in the average wages of affected workers.) In a February 2021 NBER working paper, Orley Ashenfelter of Princeton University and Štěpán Jurajda of the Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education - Economics Institute used price and wage data from McDonald's restaurants to find a strong relationship between the increase in the minimum wage and increase in restaurant wages. Although much of the wage increase was among workers near the effective minimum wage level, many restaurants sought to preserve their pay premium and thus increased wages regardless of whether the minimum wage was binding — that is, whether the minimum was higher than what their workers were already receiving.

Cengiz and his co-authors found that the benefits of wage spillovers accrue only to those who had a job before the minimum wage increase and not to new entrants. They argued that the spillovers were generated from concerns about relative pay — firms bumping up the pay of workers who were just above the minimum wage in order to preserve pay differentials within the firm — and not from the fact that the higher wage floor enticed nonemployed workers to take a job.

On one hand, if the minimum wage rises above a nonemployed worker's reservation wage (that is, the lowest wage at which a worker is willing to work), he or she will take a job. On the other hand, the rise in the minimum wage, or even the discussion of a possible minimum wage hike, could itself result in an increase in workers' reservation wages. The economy seems to be experiencing such an increase in reservation wages today — not just as a result of the $15 minimum wage discussion, but also as the result of a pandemic that had a disproportionately large impact on our lowest wage workers. (See "Do Employees Expect More Now?")

More controversial than the relationship between the minimum wage and average wages is the effect of an increase in the minimum wage on employment — at least using the minimum wage increases that have been observed in the United States. Economic theory from Econ 101 would imply that if the minimum wage acts as a price floor in a competitive labor market, then enacting a minimum wage will reduce labor demand and thus reduce employment. The evidence of an employment decline after a minimum wage increase, however, has been mixed. Broadly, the literature suggests limited aggregate employment effects but a negative employment effect for workers earning at or below the minimum wage prior to the increase. In their 2019 article, Cengiz and his co-authors found that an average minimum wage hike led to a large and statistically significant decrease in the number of jobs below the minimum wage in the five years after the minimum wage was implemented or changed. Those lost jobs were almost entirely offset by an increase in the number of jobs at or slightly above the minimum wage. This is what economists call a labor-labor substitution at the lower end of the wage distribution. The researchers found no indication of significant employment changes in the upper part of the wage distribution.

In a 2021 review of some of the literature, David Neumark of the University of California, Irvine and Peter Shirley of the West Virginia Legislature reported that 55.4 percent of the papers that they examined found employment effects that were negative and significant. They argued that the literature provides particularly compelling evidence for negative employment effects of an increased minimum wage for teens, young adults, the less educated, and the directly affected workers. On the other hand, in a 2021 Journal of Economic Perspectives article that analyzed the effect of the minimum wage on teens ages 16-19, Alan Manning of the London School of Economics and Political Science wrote that although the wage effect was sizable and robust, the employment effect was neither as easy to find nor consistent across estimations.

Thus, although the literature supports an effect on employment among the most affected workers, it does not appear to be as sizable as theory might suggest. But how else do employers respond to a forced increase in the cost of labor? For one, they could pass the cost increase along to customers — and there is some evidence for that. In a 2018 ILR Review article, Sylvia Allegretto and Michael Reich of the University of California, Berkeley found that minimum wage increases are largely absorbed by price increases. Daniel Cooper and María José Luengo-Prado of the Boston Fed and Jonathan Parker of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concluded much the same in a 2020 article in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking.

There are other ways that employers could absorb the increased wage. For one, employers could cut nonwage compensation, such as health care benefits or vacation time. Alternatively, if raising wages lowers turnover among firms, they might find that labor costs increase substantially less than the increased wage would suggest — thus accounting for the smaller employment effect. Firms might also turn to automation in the face of rising labor costs.

Another possibility is that firms do not operate in a perfectly competitive labor market. For example, firms might have monopsony power, where a firm is the price-setter of wages rather than the price-taker. (See "Raise the Wage?" Econ Focus, Third Quarter 2014.) In this model, the employer faces an increasing marginal cost per worker and thus will underpay and underemploy given the productivity of the workforce; by setting a minimum wage above what the monopsonist chooses, the government imposes a constant marginal cost per worker, thus leading the firm to both employ and pay more.

Who are the Minimum Wage Workers?

The complex and regional nature of minimum wage legislation makes it more complicated than one would think to understand exactly which workers are affected by minimum wage legislation. Roughly 139 million employees, or 85 percent of the U.S. workforce, qualify for FLSA protections. Employees in certain occupations and industries (for instance, individuals elected to state and local offices and their staffs) are not covered by the FLSA. Even for those who qualify for FLSA coverage, there are exemptions to the minimum wage requirement for some employees (for instance, employees in some computer-related occupations who pass salary and duties tests) and subminimum wage provisions for workers including new hires under age 20, full-time students, employees with disabilities, and tipped workers.

Nationwide, the share of U.S. workers earning at or below the minimum wage is small. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers report, in 2020, 55.5 percent of all wage and salaried workers, or 73.3 million workers ages 16 and older, were paid hourly. Of these workers, 1.5 percent reported earning at or below the federal minimum wage in 2020, compared to 13.4 percent in 1979. According to the same report, in the Fifth District, the share of hourly workers at or below the federal minimum ranged from 1.8 percent in the District of Columbia and North Carolina to 4.4 percent in South Carolina. This can, of course, vary notably by age group. According to Alan Manning in a 2021 Journal of Economic Perspectives article, more than 25 percent of teens reported an hourly wage at or below the minimum in 2019. Yet they represent only about 10 percent of all minimum wage workers in 2019 compared to about a third of minimum wage workers in 1979.

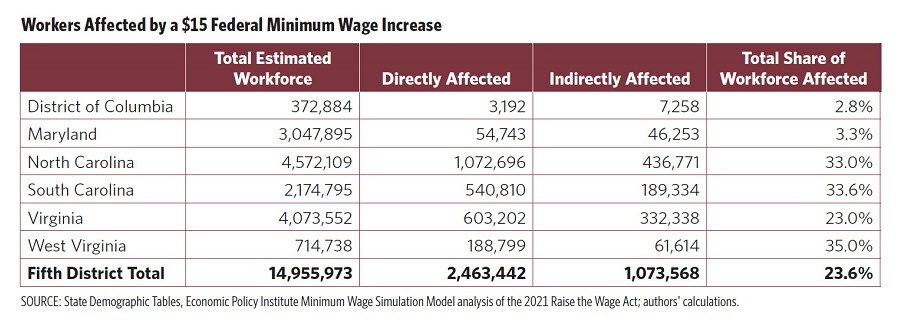

Understanding the effect of a $15 minimum wage requires figuring out the number of workers who make less than $15 per hour, not less than the current $7.25. Also, most minimum wage laws increase the wage over time, so any analysis would have to assess how many workers will make less than $15 in the future, thus requiring a forecast of market-based wage growth. For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analyzed the proposed Raise the Wage Act of 2021 — which would raise the federal minimum wage in annual increments to $15 by June 2025 and then increase it at the same rate as median hourly wages — and estimated that by 2025, 17 million workers, or 10 percent of the projected labor force, will earn less than $15 per hour during an average week in 2025.

In addition, the CBO — consistent with findings in the literature — assumed that the 10 million workers who would have wages only slightly higher than the proposed minimums would also be "potentially affected" on the basis that employers would retain some pay differences across their workforce. Therefore, according to this analysis, increasing the minimum wage to $15 through the proposed legislation would affect the pay of about 27 million workers nationwide.

Under different assumptions, particularly about nominal wage growth for low-wage workers, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Minimum Wage Simulation Model estimates that the Raise the Wage Act could affect the pay of roughly 32 million U.S. workers by 2025 — considerably more than the CBO estimate. Because of the act's provision to phase out the tipped worker subminimum wage — increasing it from $2.13 in 2021 to $12.95 by 2025 — even states that will have $15 per hour (or higher) minimum wages in 2025 will see an increase in the number of affected workers. EPI estimates that 2.46 million workers in the Fifth District would be directly affected by the Raise the Wage Act, as would the additional 1.07 million workers making between the new minimum wage and 115 percent of the new minimum. (The 1.07 million workers are comparable to the CBO's "potentially affected" workers.) West Virginia and the Carolinas, where the minimum wage is at or slightly above the prevailing federal level and where there are no planned increases, would see the largest share of their workforces affected by 2025. (See table below.)