The Bank War

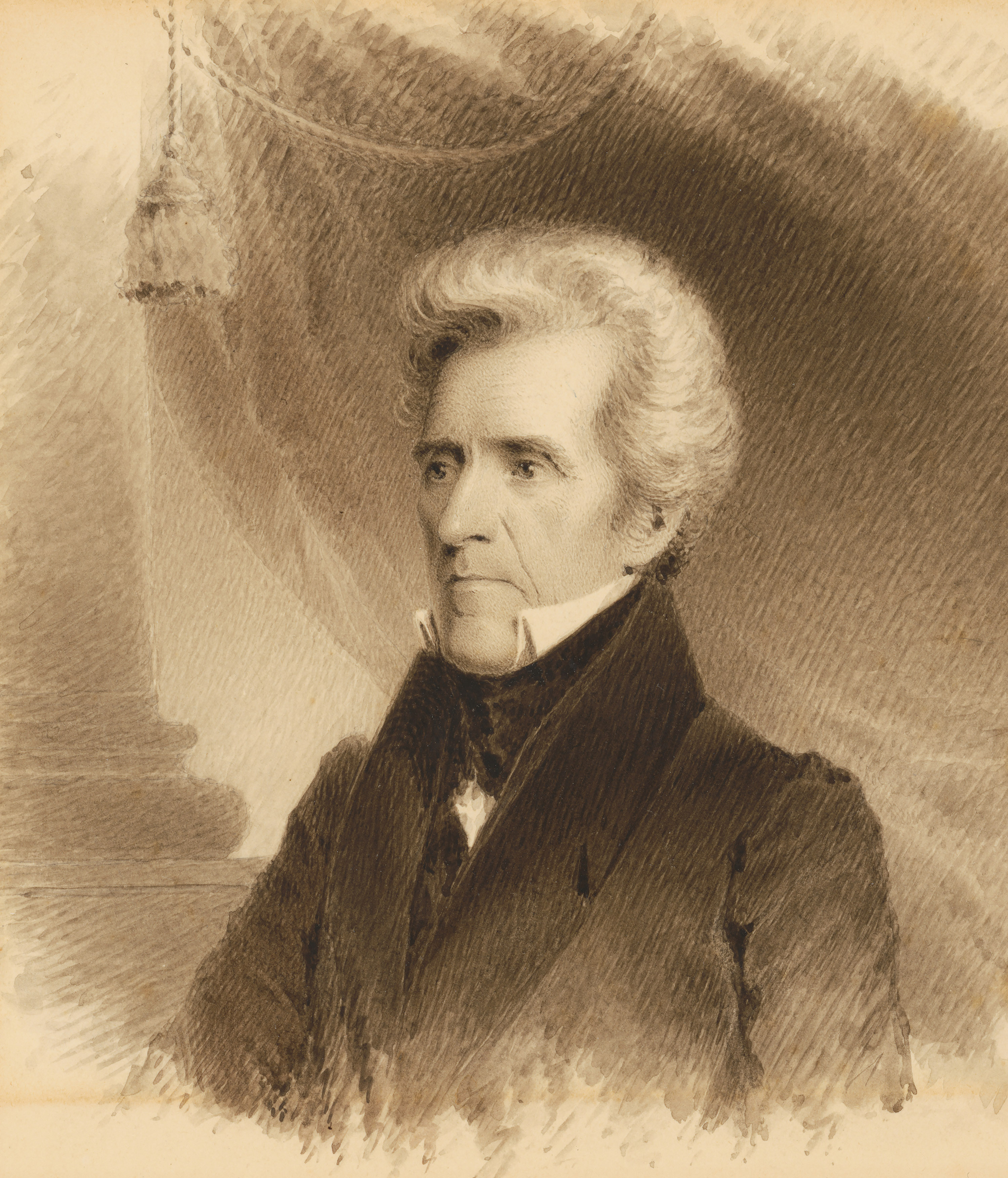

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson triggered the demise of America's second central bank with a stroke of his veto pen

The Fits and Starts of Early Central Banking

Congress and President George Washington granted a 20-year charter to the Bank of the United States in 1791. Designed by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, it had the power to make commercial and personal loans that would be used to fund the new country's growth, print and issue a common paper currency backed by gold, loan money to the government when needed, and collect revenues and make payments, such as the debts from the Revolutionary War. Thomas Jefferson, the secretary of state, opposed it, however, seeing the potential for too much centralization of power in an entity not even mentioned in the Constitution.

Twenty years later, in 1811, the bank's charter was not renewed. Hamilton had been killed in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, and his (and Washington's) party, the Federalists, had lost power to James Madison's (and Jefferson's) Democratic-Republican Party, which viewed the bank as both unconstitutional and unnecessary, as outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War were largely repaid at that point.

Instead of a national bank, the American economy relied on a system of independent state-chartered banks during this period. They served many of the same functions, including issuing their own paper currencies, which could be redeemed at their own counters for gold and silver specie, or coins, at the same convertibility standard.

But as the costs of the War of 1812 escalated, these banks suspended specie payments in 1814 because the notes used to pay those debts increased faster than the volume of specie reserves. (In other words, there was not enough specie in the banks to exchange for all the notes they had issued.) This inflationary practice destabilized the economy and convinced a reluctant Madison that, despite any misgivings he might have about the constitutionality of a central bank, it was once again needed to establish a stable national currency. In addition to printing its own notes, it would also exert control over the other banks by threatening to redeem their notes for specie if it had reason to believe that they had issued too many of them.

The bill chartering a Second Bank of the United States passed both houses of Congress and in April 1816, Madison signed it into law. The decision was widely welcomed by New York-based businessmen, including the financier John Jacob Astor, whose interests would most certainly benefit from monetary stability and the end of wild inflationary swings. As for popular opinion, Vanderbilt University economist Peter Rousseau says that, in contrast to wealthy eastern bankers, most people throughout the country were paying attention to the debate about the bank only insofar as it affected their ability to do business. "I don't think people were thinking too much about the control structure, but those who were more aware of what was going on saw a constriction of credit" because of a centralized banking system, Rousseau notes. "There just weren't enough banks."

A Gathering Storm

Like the First Bank of the United States, the Second Bank would act as the federal government's fiscal agent, issue a common currency, and make direct commercial and individual loans. It was this last function that perhaps would be the most controversial. In the absence of any meaningful oversight, many of these loans were large and nonperforming and made to insiders and friends. This left the bank on the brink of bankruptcy just two years into its existence. Such behavior typified the problem that concerned Jefferson and other early opponents — it could be used for corrupt purposes, funneling money to political allies to the detriment of the broader population. A century later, in 1913, Congress would learn from these experiences and permit the Fed to lend only to banks and other financial institutions. (In 1932, Congress allowed for exceptions to be made in "unusual and exigent circumstances.") But in the more immediate future, it would also be one of Andrew Jackson's chief complaints about the bank when he assumed the presidency in early 1829.

War Erupts

Jackson's belief that he could veto the bank's recharter and still win the election was correct, as he went on to win over four times as many electoral votes as his opponent, Henry Clay. "Jackson staked his whole reelection campaign on destroying the bank," says Eric Hilt, an economist at Wellesley College, "and his victory is a sign that sufficient numbers of Americans shared his fear and skepticism of the institution."

The concerns Jackson voiced in his veto message were also echoed by his then-attorney general and soon-to-be Treasury secretary, Roger Taney. (Taney, in 1836, would become chief justice of the United States and later wrote the infamous pro-slavery Dred Scott decision.) He claimed that unless the bank was destroyed rather than reformed, "In another fifteen years, the President of the Bank...would have more influence...than the President of the U[nited] States." Almost immediately into his second term, Jackson, Taney, and their allies set to work dismantling the bank.

"The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 in the Stream of U.S. Monetary History," Economic Review, July/August 1988

Any questions about whether a national bank could exist within the limits of the Constitution were settled in 1819, when the Supreme Court found in McCulloch v. Maryland that Congress did, indeed, have the authority to charter the Second Bank of the United States, as it was "necessary and proper" under its authority to tax and spend. But in late 1833, now Treasury Secretary Taney ordered that the government's deposits be removed from the bank, hampering its ability to carry out what the court had found to be acceptable and even crucial bank activity. He drew justification from the text of the bank's 1816 Act of Incorporation, which stated that the "deposits of the money of the United States... shall be made in said Bank or Branches thereof, unless the Secretary of the Treasury shall otherwise order and direct..." The withdrawal was significant: The bank held $7.5 million in deposits in November 1833 but only around $2 million in March the following year.

Biddle had hoped Congress would intervene and stop the administration's removal of deposits. He wrote in February 1834 that if it did not take action to restore the bank's capabilities, "the Bank feels no vocation to redress the wrongs inflicted by these miserable people... This worthy President thinks that because he has scalped Indians and imprisoned Judges, he is to have his way with the Bank. He is mistaken."

In an episode known as "Biddle's Contraction," Biddle responded to the deposit removal by drastically cutting the bank's lending operations and calling in its outstanding loans. From 1824 to 1831, perhaps in an effort to curry favor with influential actors in the run-up to the rechartering debate, he had dramatically increased the bank's lending activity. But following Jackson's veto and subsequent removal of deposits, the Second Bank's loans fell from a high of 53 percent of assets in 1832 to around 40 percent in 1835. Because of his decision to curtail the bank's lending activity, historian Edward Pessen described Biddle as "a man fighting fire with fire, ready to drive banks to their knees and bring economic activity to a halt, if to do so might compel the government to reconsider its policy."

The issue drew attention across the country. Harvard University political scientists Daniel Carpenter and Benjamin Schneer found in a 2015 paper that between December 1833 and June 1834 more than 700 petitions were submitted to Congress about the deposit issue. Seventy percent of those petitions, some of which contained hundreds or even thousands of signatures, were in favor of returning deposits to the bank. But the petitions weren't enough. Even though constituent input appeared to favor action, Congress ultimately did not rescue the bank and force Jackson to return the deposits.

While some of the reduction in lending was because there was less government money in the bank to be lent out, Biddle's actions created a minor panic. According to Carpenter and Schneer, "Biddle's plan massively backfired, generating resentment in the business community and all but proving President Jackson's point that the powers of finance were not to be entrusted to a single incorporated institution." At this point, Biddle realized that the game was up and relented. To not cause further damage, he soon increased the bank's provision of credit back to its previously elevated level near 50 percent of assets.

The Aftermath

Andrew Jackson had railed against the use of the national bank for political purposes by his opponents, but he was more than willing to grant special privileges to state-chartered banks, particularly those that were, according to Treasury Department official and influential "Kitchen Cabinet" member Amos Kendall, "in hands politically friendly." Perhaps surprisingly, and in contrast to his efforts to portray himself as hostile to wealthy eastern elites, Jackson had Taney initially transfer the deposits that had been removed from the Second Bank to seven large banks all located on the East Coast, including the Union Bank of Baltimore, where Taney was a stockholder. He would later order that they be redistributed to "pet banks" throughout the country that had close relationships with Jackson and his administration.

Under this new system, the federal government paid off its debts in January 1835, thanks in large part to the sale of public lands in the Midwest, Mississippi, and Louisiana, as well as an increase in customs duties. The financial position of the United States was so strong, in fact, that its surplus in June 1836 had soared to $34 million. State-chartered banks also flourished during this period.

But the good times would be replaced by the Panic of 1837. While a number of domestic and international factors contributed to the downturn, the absence of a central bank played a key role as well. Economist Jane Knodell of the University of Vermont argued in a 2006 paper that the ending of the Second Bank created a mismatch between the supply of and demand for commercial banking in different parts of the country, especially in the Northwest and Southwest. The shift to a system solely comprised of state-level banking altered the lending behavior of those banks, which now carried obligations to the state governments that chartered them, as well as their shareholders. As a result, they invested more heavily in land development and state public works projects, which the Second Bank had avoided.

Further, when there isn't deposit insurance, depositors tend to monitor the banks where they put their money to make sure they aren't engaging in overly risky lending behavior. In the case of the pet banks, however, many of which were in the western states, the federal government just parked its vast sums of money and stopped paying attention. "Huge deposits from the federal government were coming in, and there was no discipline," says Hilt. "Instead, there was a totally safe source of funding that protected the banks from the usual pressures that depositors would bring." This lack of oversight allowed the banks to make dangerous bets even as land and commodity prices plummeted, and by 1837, the economy had ground to a halt and would remain depressed until the mid-1840s.

The events surrounding the Bank War provided future policymakers with some important lessons. In a 2021 paper, Rousseau argued that "the legacy of the Second BUS [Bank of the United States] is the principle that a central bank should be independent but not excessively so, and must stand ready to monitor its members." Central banking in the United States has evolved in those two directions. With respect to the latter, the Fed is among the agencies explicitly tasked by Congress with supervising the country's banks to ensure they operate prudently. Regarding the former, the Fed's activities are in the hands of a board — nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate — and of regional Reserve Bank presidents, under the oversight of Congress. And for over a hundred years, it has helped manage the country's financial system as it continues to grow and evolve.

Readings

Carpenter, Daniel and Benjamin Schneer. "Party Formation through Petitions: The Whigs and the Bank War of 1832-1834." Studies in American Political Development, October 2015, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 213-234.

Erickson, David J. "Before the Fed: The Historical Precedents of the Federal Reserve System." Federal Reserve History, December 2015.

Hill, Andrew T. "The Second Bank of the United States." Federal Reserve History, December 2015.

Knodell, Jane. "Rethinking the Jacksonian Economy: The Impact of the 1832 Bank Veto on Commercial Banking." Journal of Economic History, September 2006, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 541-574.

Morrison, James A. "This Means (Bank) War! Corruption and Credible Commitments in the Collapse of the Second Bank of the United States." Journal of the History of Economic Thought, June 2015, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 221-245.

Rousseau, Peter L. "Jackson, the Bank War, and the Legacy of the Second Bank of the United States." AEA Papers and Proceedings, May 2021, vol. 111, pp. 501-507.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.