Did U.S. Immigration Policy Influence India’s IT Boom?

We highlight an unintended consequence of U.S. immigration policy for high-skill workers. Indian college students and workers got skills in computer science in the 1990s — a key occupation for innovation and growth — with the prospects of migrating to work in the booming U.S. IT industry. However, many ended up not migrating or returning to India after a short period. These workers helped build the IT sector in India, which grew at outstanding rates in the late 2000s.

Migration across countries has different implications for the country that sends the immigrants and the country that receives them. Receiving economies want to understand how immigrants affect local productivity and production as well as labor market and human capital decisions of native workers. Sending economies want to understand whether workers who migrate generate a net loss for the country due to losing key talent (a phenomenon known as brain drain) or perhaps continue generating benefits for the sending country even after leaving.

In our project "The IT Boom and Other Unintended Consequences of Chasing the American Dream," we focus on understanding these channels to evaluate the impact of U.S. high-skill immigration policy for India and the U.S. Our hypothesis is as follows.

The U.S. information technology (IT) sector developed rapidly in the 1990s and pushed up demand for computer scientists.1 A large part of that demand was satisfied with immigrants coming from India under the H-1B visa program. College students and graduates in India knew that increasing their skills in computer science would also significantly enhance their probability of migrating to the U.S. Hence, some Indians selected computer science majors and occupations with the prospects of migrating.

However, many of those ended up staying in India or returning after a short period in the U.S. due to the restrictive nature of U.S. immigration policy. Those who stayed or returned to India helped develop the IT sector domestically and built a computer science workforce that contributed to India's IT boom in the late 2000s. If more people who studied computer science stayed instead of leaving, the possibility of migration to the U.S. would have created a "brain gain" of computer scientists in India as opposed to a "brain drain."

In this article, we discuss some trends that support our hypothesis and discuss how our understanding of immigration policy might change when we consider the possibility of the sending country acquiring valuable skills in response to immigration prospects.

The U.S. IT Boom and the Demand for Computer Science Skills

Technological innovations in the early 1990s — such as using the internet for commercial purposes — pushed the development of the U.S. IT sector. These new technologies increased the demand for a very specific type of skills: computer science. This led to a boom in the IT sector in the second half of the 1990s, during which California's Silicon Valley became the global epicenter of software development and production.

During this period, the number of U.S.-based computer scientists almost doubled, going from 0.82 million in 1995 to 1.53 million in 2001. A big part of this growth was met by hiring computer scientists from abroad to come work in the U.S. Immigrants went from 14 percent of the U.S.'s computer science workforce in 1995 to 25.7 percent in 2001.

U.S. immigration policy also responded to help meet the increasing demand. The influx of immigrant computer scientists into the U.S. was mainly facilitated through the H-1B visa program, through which companies can sponsor college-educated workers to come work in the U.S. In 1995, new H-1B visas were capped at 65,000 per year. Given rapidly increasing demand, Congress expanded the cap in 1999 to 115,000 new visas and again in 2001 to 195,000 new visas. After 2001, growth in the U.S. IT sector stalled — largely due to the so-called dot-com bust — and Congress decreased the H-1B cap to its current annual limit of 85,000 new visas.

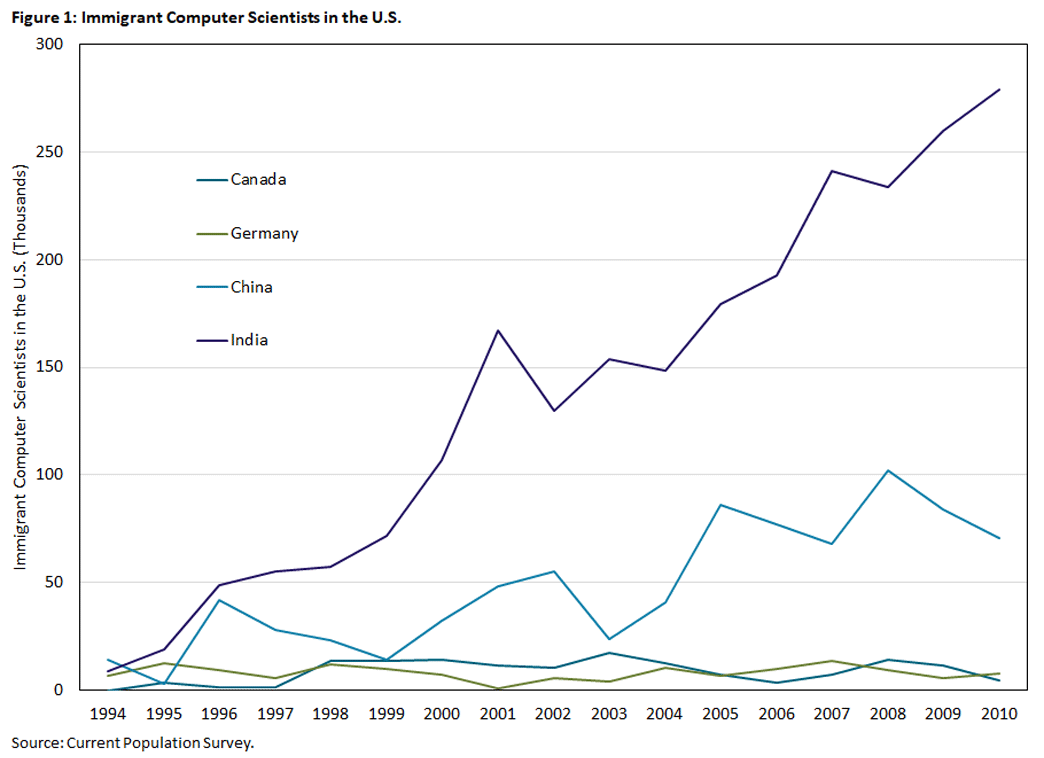

As shown in Figure 1, Indians represented a majority of computer science foreign workers. By 2010, 300,000 Indian computer scientists were working in the U.S., and they represented 14 percent of the total immigrant workforce and 56 percent of the immigrant computer science workforce.

While many countries sent immigrants to the U.S., India is a special case for computer science and engineering. First, India had made large investments in top engineering schools starting in the 1950s that built a strong worldwide reputation. Second, India has large population of English-speaking workers and has lower wage levels compared to other countries with skilled engineering workforces such as Germany, Israel or Ireland.

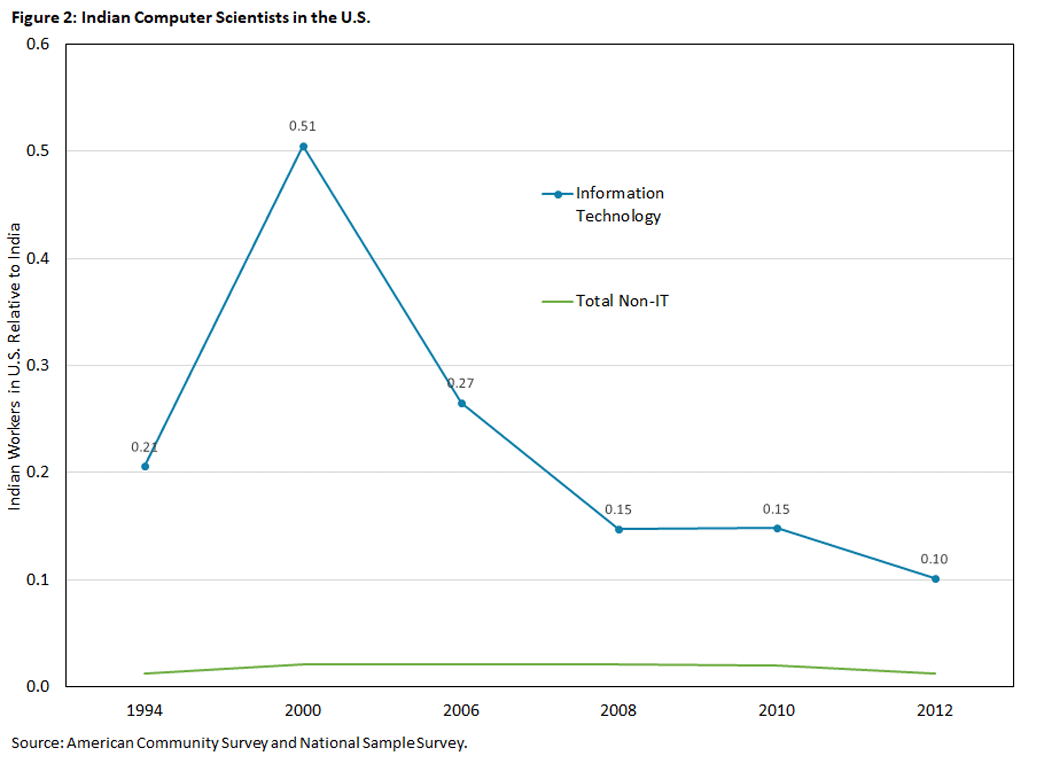

In the 1990s, India's IT sector was just starting, and internal demand for computer scientists was low. As such, the U.S. was a major employer for Indian computer scientists. As shown in Figure 2, there was one Indian computer scientist working in the U.S. for every two Indian computer scientists working in India by 2000.

This ratio decreased in the late 2000s once India's domestic IT sector developed, but the U.S. remained an important source of labor demand. The wages paid to computer scientists in the U.S. were significantly higher, with computer scientists in the U.S. earning eight times higher wages than in India in 1995 and four times higher wages in 2010.

The Impact of U.S. Demand on Indian College Decisions

Given the large wage differential across countries and the important relative demand from the U.S. for computer science skills, students and workers in India are likely to take that into account when choosing their college majors and occupations.

To understand whether migration prospects in the U.S. drive enrollment decisions, we dive deeper into college major choices within India. First, we rank Indian states based on their propensity to send migrants to the U.S. We use data from LinkedIn and record the universities of Indian college graduates residing in the U.S. who graduated before 1995. Then, we aggregate graduates by Indian state and calculate the "baseline migration intensity," which is the number of migrants from a given state relative to the number of engineers in that state in 1992. Figure 3 plots the total enrollment in engineering for each migration quartile, where the fourth quartile contains the regions with the highest migration intensities and the first quartile contains the regions with the lowest.

As shown in Figure 3, the number of students enrolled in engineering is relatively constant for each quartile until 1998. After that, the fourth quartile starts to sharply increase until 2003, where it experiences a small dip. This movement parallels the increase and decrease of the H-1B cap.

After 2004, both the third and fourth quartiles increase by similar proportions, driven predominantly by local demand for engineers. This evidence further suggests that enrollment in engineering did respond to migration incentives.

We argue that, given the restrictiveness of U.S. H-1B program, it is uncertain that Indian workers will end up migrating to the U.S. even if they acquire the skills to migrate. First, workers need to find employers that wants to sponsor them for visas. Second, if the total number of H-1B applications exceeds the H-1B cap, visas get awarded randomly though a lottery, which adds uncertainty to the process. Third, even if workers do migrate, they might need to go back to India if their employers are not willing to extend their H-1B visas or sponsor them for green cards.

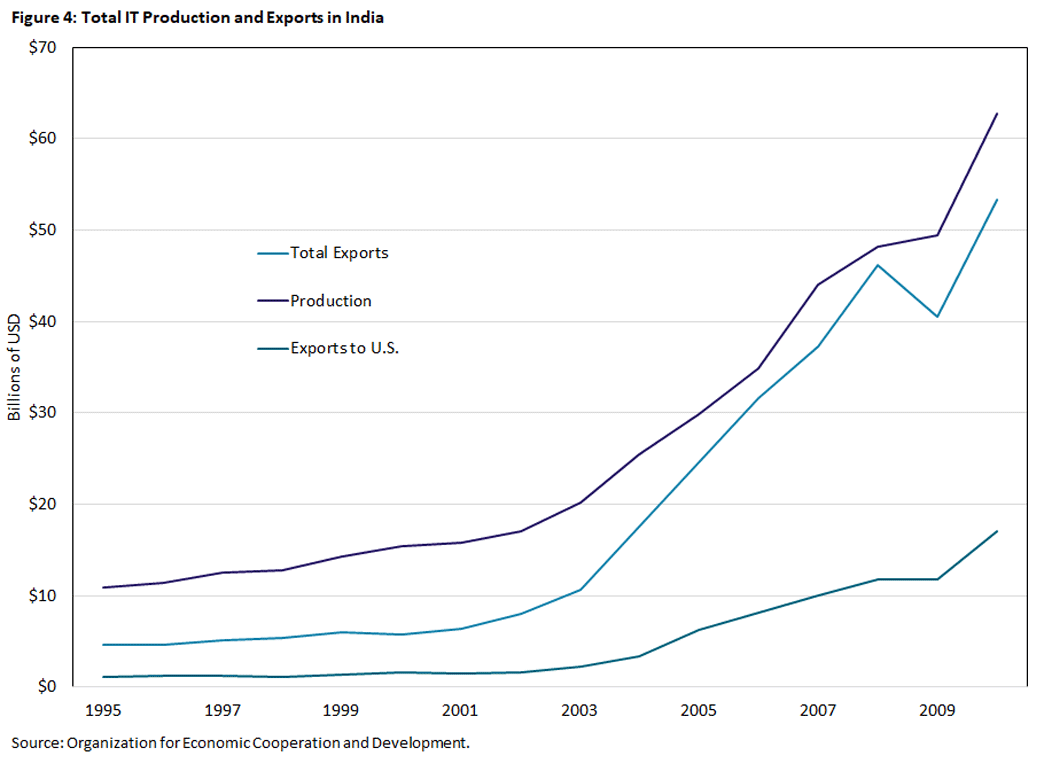

The computer science workforce that stayed or returned to India likely helped develop the IT sector domestically. In fact, India saw tremendous growth in IT production, particularly after 2004. Such growth was mostly driven by exports, as shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, most exports were not to the U.S. but to the rest of the world. As such, India surpassed the U.S. in the mid-2000s as the global exporter of IT goods to the rest of the world.

Policy Implications

So far, we showed multiple trends suggesting that the U.S. IT boom coupled with a restrictive immigration policy might have encouraged Indians to get computer science skills. While many migrated, others stayed or returned after a short period in the U.S. and helped develop India's IT sector. In our paper, we then build a model of the world economy where we simulate how an even more restrictive immigration policy would affect the U.S. and India.

We show that if the H-1B cap had been 50 percent lower between 1995 and 2010, workers in both countries would have suffered. In the U.S., Indian computer scientists were valuable for innovation and brought skills that were complementary to U.S. non-college graduates and college graduates with majors other than computer science. The value lost due to restricting immigration in this scenario is at least partly compensated by the gains of native computer scientists who are now more protected from the extra competition effect with Indian computer scientists. If immigration is restricted, some natives would gravitate to computer science occupations, mitigating the loss of computer science skills in the U.S.

In India, we find that workers are worse off under a more restrictive U.S. policy. A large part of this loss is that, with harsher restrictions, fewer Indians choose to study and work as computer scientists, lowering the rate of innovation and growth in the economy. India's IT sector would be 35 percent lower under the more restrictive immigration policy.

To sum up, the uncertainty on migration when making human capital decisions generated a "brain gain" in India, where many of those who acquired computer science skills ended up not migrating and helped develop the IT sector in India. While India could better compete with the U.S. in the global market, the net effect might not have been harmful for the U.S., whose workers also benefitted from migration due to higher productivity, lower prices and higher wages for workers with complementary skills to the immigrants.

Gaurav Khanna is an assistant professor of economics at the University of California-San Diego. Nicolas Morales is an economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

In this article, we use the term "computer scientists" to also refer to computer software developers and computer systems analysts as well as computer scientists as per CPS 1990 occupation classification.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Khanna, Gaurav; and Morales, Nicolas. (December 2023) "Did U.S. Immigration Policy Influence India's IT Boom?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 23-42.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.