Inflation Expectations and Price Setting Among Fifth District Firms

Evidence from a Federal Reserve Fifth District survey indicates that businesses become more reactive to inflation as it rises, but much of that reactivity reverses as inflation ebbs. Moreover, the survey indicates that inflation expectations matter to how most firms set their prices. How much inflation expectations matter and for whom they matter are essential questions for policymakers as they seek to maintain price stability.

As inflation surged in the last few years, a key concern has been that firms and workers would perceive higher inflation as a persistent feature of their environment. In such circumstances, pricing shocks that typically generate short-lived inflation may instead be interpreted as information about future inflation. Firms would then post higher prices, and workers would request higher wages, validating those inflationary beliefs. This is concerning because such "unanchoring" of inflation expectations was a factor behind stagflation in the 1970s and the considerable cost of disinflation in the 1980s. This has motivated central banks around the world to take aggressive early stances to keep inflation expectations low and thus avoid harder trade-offs in the future.

In March 2022, we wrote an article that introduced a series of questions that measure the relationship between aggregate inflation and firms' expectations for their costs and prices. At that time, three waves of the quarterly survey suggested that business leaders were increasingly attentive to inflation and incorporating aggregate inflation expectations into their decision-making and price/cost expectations. We now have six additional waves of the quarterly survey through October 2023. The two most recent waves suggest that firms might slowly return to their July 2021 levels of attention and reactivity to aggregate inflation measures: At the very least, the trend has shifted.

It is crucial to assess the role of expectations in the economic choices of firms and households to better assess whether influencing expectations can be an effective monetary policy tool.1 There has been ample research on the factors that affect how firms and households form inflation expectations,2 but there has been relatively less empirical work to understand how expectations affect actions. Our new survey instrument attempts to do just that: understand how firms' inflation expectations feed into their price setting.

Most importantly, the questions added to the Richmond Fed business surveys provide some visibility into how those feedback mechanisms depend on the level of inflation. The findings so far suggest that businesses reported becoming more reactive to inflation news as inflation surged, but much of that was reversed as inflation ebbed. Thus, the results validate efforts to actively keep inflation under control rather than letting underlying shocks play out.

Inflation Expectations Rise and Become More Dispersed with Inflation

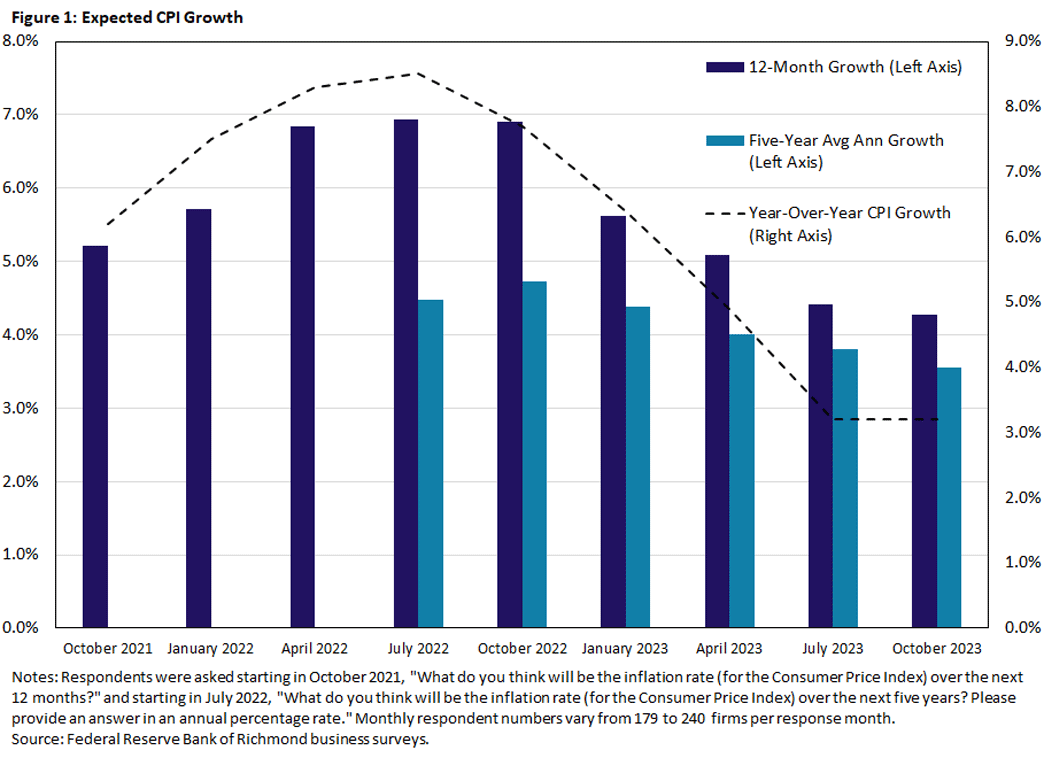

Like inflation itself, inflation expectations among firms and households have come down from their peak in 2022. Among surveyed firms in the Fifth District, the average expected consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate has fallen from a peak of almost 7 percent in July 2022 to a little more than 4 percent in 2023, as seen in Figure 1. Similarly, average annual expectations for inflation over the next five years have come down since we started asking about them in July 2022.

In most surveys, firms' inflation expectations are above those of professional forecasters, but an expectation of 4.3 percent is also higher than most surveys found prior to the inflationary episode. For example, in one survey of firm inflation expectations, respondent firms' expectations averaged well above 3 percent in 2018 but fell to around 2 percent in 2019 and remained there until 2021.3

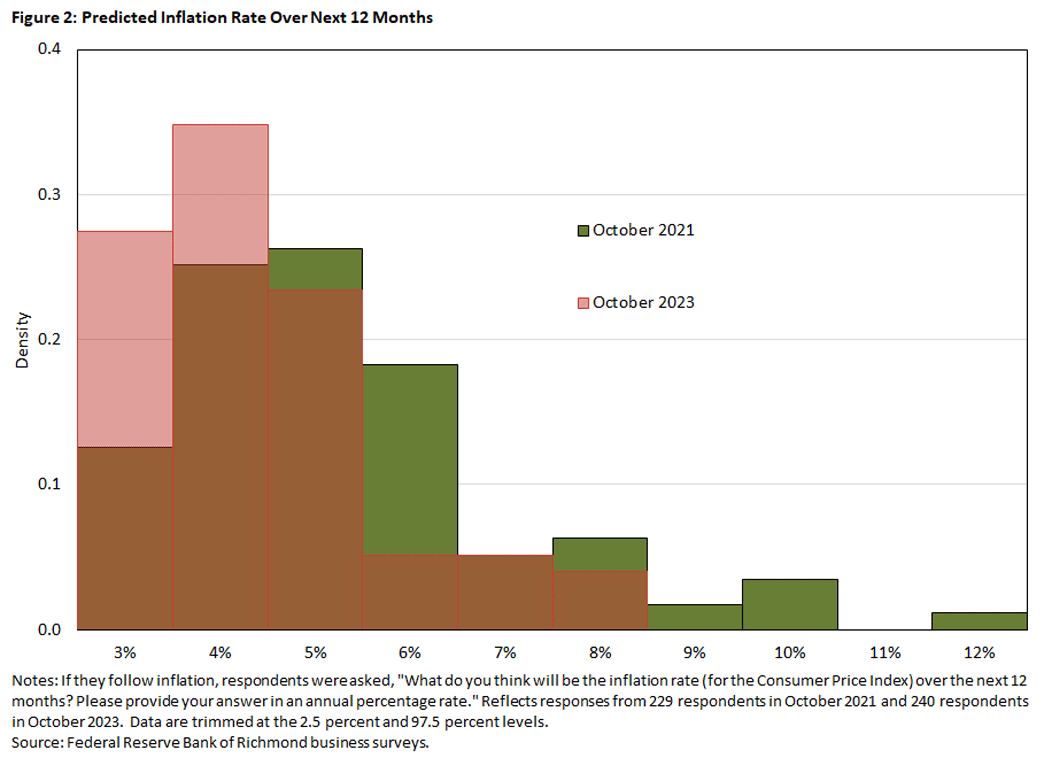

We also see declines in both dispersion and skewness of inflation expectations, as displayed in Figure 2. Such increases in measures of disagreement or skewness in inflation expectations can be an early indicator of the unanchoring of inflation expectations.4 Thus, a decline in dispersion and skewness could indicate a return to normalcy.

Firms Pay More Attention to Inflation as It Rises

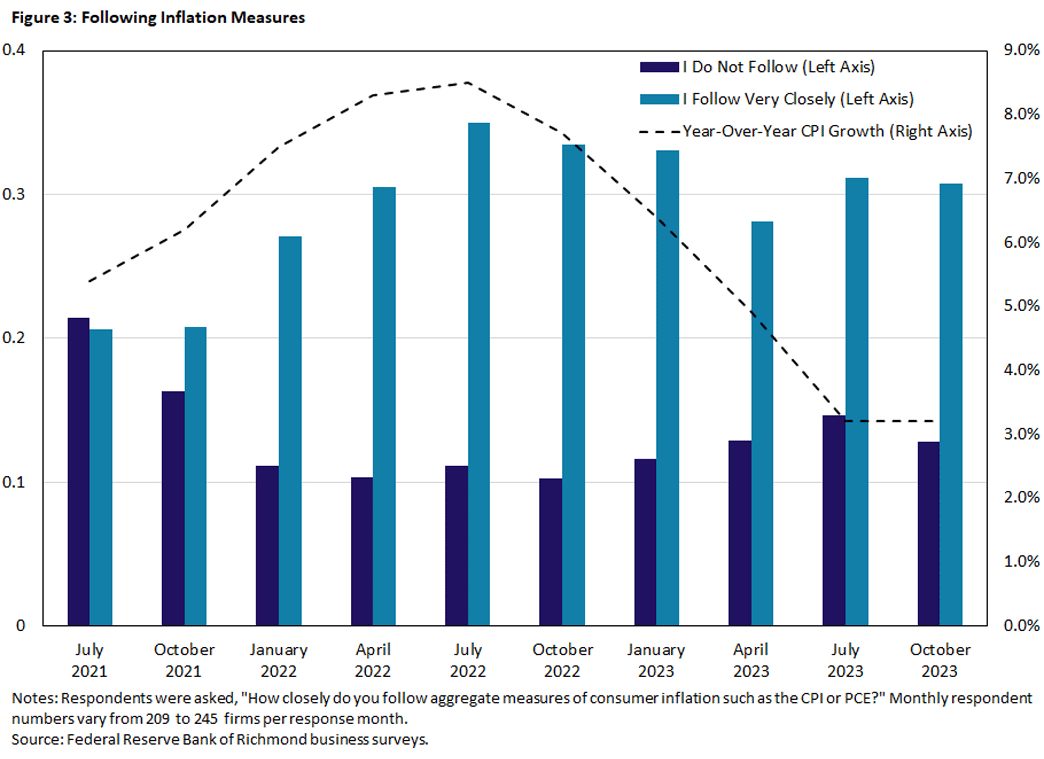

The survey finds significant changes in the extent to which firms report following inflation over our sample period, as seen in Figure 3. The decline in the share of respondents that do not follow inflation at all from over 20 percent in July 2021 to just over 10 percent in July 2022 was statistically significant at the 95 percent level, as was the corresponding increase in the share of those who follow very closely (from about 20 percent to about 35 percent).

Conversely, by October, the share of respondents who do not follow inflation at all rose to 13 percent of respondents, and the share that follow very closely declined to 30 percent. The latter findings are not, however, statistically significantly different from the low/peak that we saw in July/October 2022.

It is possible that the rising inflation in 2021 and 2022 had a positive effect on how much firms pay attention to inflation.5 This is consistent with previous work, which has found (using cross-country firm survey data) that firms in countries with higher inflation rates pay more attention than those in lower-inflation environments.6

It is also possible, however, that our survey respondents are learning about inflation through the survey itself. We find that 75 percent of firms that responded to the survey responded in at least two of the nine waves, and almost half of respondents responded in at least five of the nine waves. Relying on repeat survey participants can bias survey results in systematic ways as participants become more informed and, thus, less representative of the broader population.7 Nevertheless, we take the fact that attention appears to have receded in recent months as some indication that the attention we measure is responsive to the economic environment.

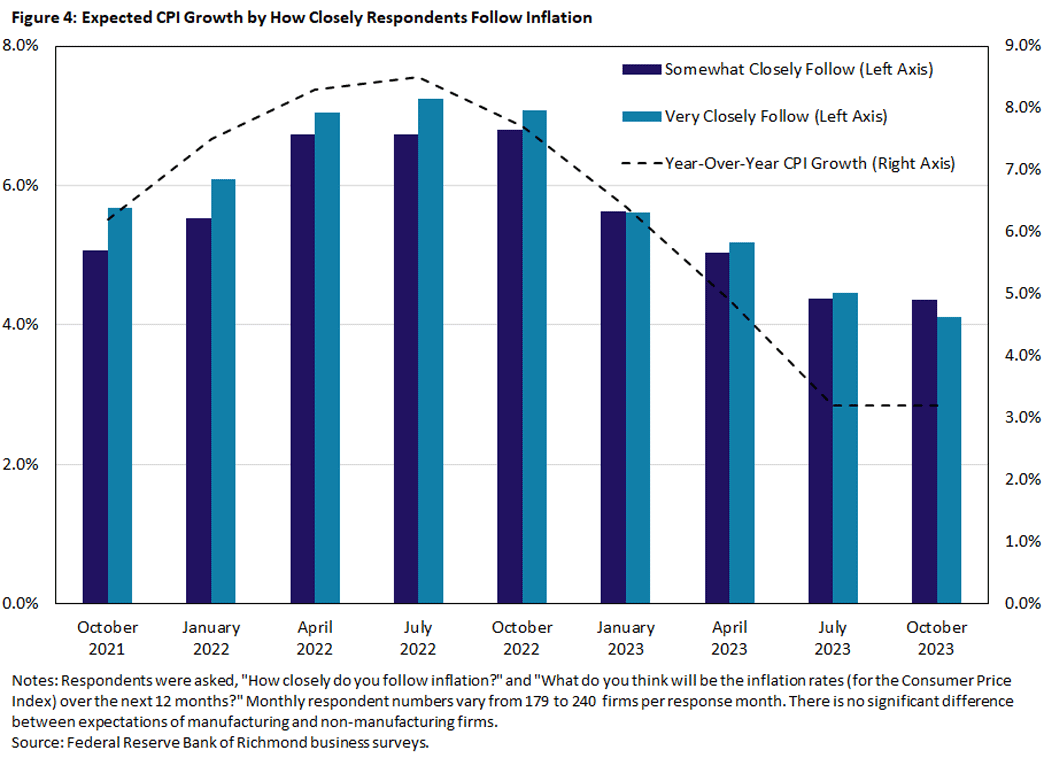

The Connection Between Following Inflation and Inflation Expectations

Attention to inflation rose over our survey waves, but how does following inflation affect expectations? We ask firms that report following inflation for their inflation expectations. On average, those that follow "somewhat closely" had consistently lower expectations for aggregate inflation than those that follow "very closely," with the ranking reversing slightly only in the last wave following a few months of surprisingly low inflation data.8 The reversal of the ranking in the last month is not statistically significant, so the pattern could follow from firms that are more worried about inflation paying more attention. To the extent, however, that this reversal continues, the pattern is consistent with firms that report paying less attention to inflation also being less sensitive to incoming information, as predicted by theory.

The Importance of Inflation Expectations to Price Setting

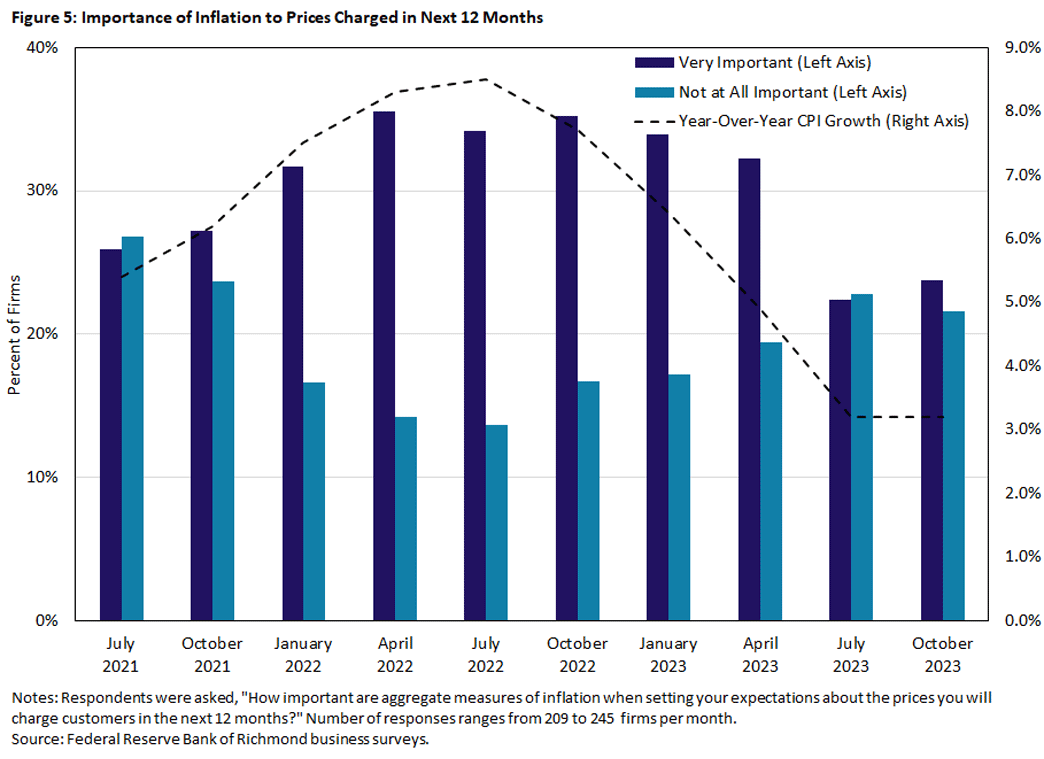

We also ask firms how important their inflation expectations are to how they set their own prices. Here, too, we saw a notable increase in firms' reported importance of inflation expectations from July 2021 to July 2022 and a reversion back by October 2023, as displayed in Figure 5.

There also seems to be a relationship between CPI growth and the relevance firms place on overall inflation for their pricing. In months where a larger share of respondents reported that inflation is "very important" to their price-setting, the average CPI reading was higher than in months where fewer reported that inflation is "very important."

As inflation has come down, the additional effect of inflation expectations on how firms set their prices has dissipated. Therefore, even if firms are learning about inflation through surveys, they are not more likely to report incorporating inflation expectations into their price-setting. This suggests that the movements in the reported effect of inflation on price-setting is unlikely to be contaminated by effects of the survey itself on firm expectations.

Firms That Expect Higher Overall Inflation Also Expect to Set Higher Prices

For decades, the Richmond Fed has asked Fifth District firms for their own realized price changes in the prior year and expected price changes for the following year. Those have proven to be highly correlated with producer and consumer price indexes, with all measures rising notably in 2021 and 2022 and then coming down.

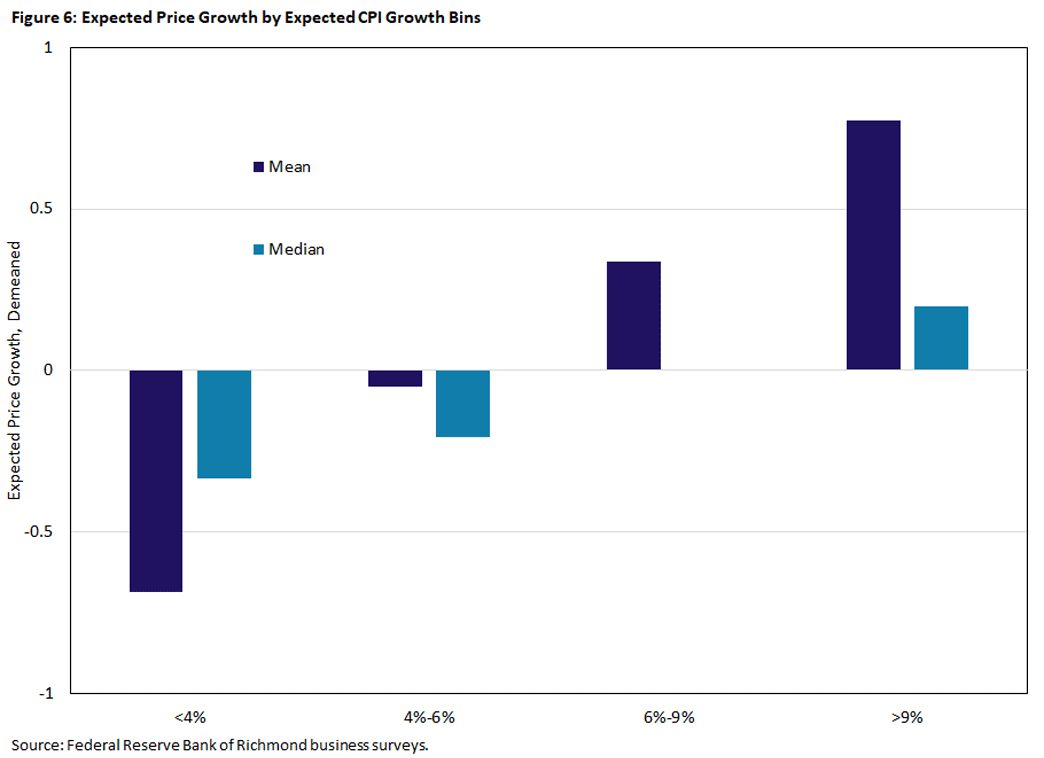

We find evidence that firms expect to increase their prices by more when they expect higher CPI growth. The chart below illustrates this relationship: Controlling for an individual's firm's average price growth (fixed effect), we find that price growth increases with own-inflation expectations. Controlling for both expected price growth and expected inflation yields, again, a statistically significant relationship, although the explanatory value is limited: Inflation expectations are, of course, one among many things that matter to firms' expected price growth.

Summary: Attention, Inflation and Prices

As inflation rose, so too did the extent to which firms paid attention to inflation. The firms that pay more attention also have higher expectations for future inflation. As inflation has come down, much of that effect has now dissipated.

We find evidence that inflation expectations matter. How much inflation expectations matter and for whom they matter are essential questions for policymakers as they seek to maintain price stability.

Felipe Schwartzman is a senior economist and Sonya Ravindranath Waddell is a vice president and economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See, for example, the 2022 paper "The Subjective Inflation Expectations of Households and Firms: Measurement, Determinants and Implications" by Michael Weber, Francesco D'Acunto, Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Olivier Coibion.

See, for example, the 2023 working paper "Information and the Formation of Inflation Expectations by Firms: Evidence from a Survey of Israeli Firms" by Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Rafi Melnick and Ari Kutai.

See the 2021 working paper "The Inflation Expectations of U.S. Firms: Evidence From a New Survey" by Bernardo Candia, Olivier Coibion and Yuriy Gorodnichenko.

See, for example, the 2021 paper "Losing the Inflation Anchor" by Ricardo Reis and Yuriy Gorodnichenko.

This was argued in 2023 working paper "Tell Me Something I Don't Already Know: Learning in Low and High Inflation Settings" by Michael Weber, Bernardo Candia, Tiziano Ropele, Rodrigo Lluberas, Serafin Frache, Brent Meyer, Saten Kumar, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Dimitris Georgarakos, Olivier Coibion, Geoff Kenny and Jorge Ponce.

See the previously cited paper "The Inflation Expectations of U.S. Firms."

See, for example, the 2023 paper "Learning-Through-Survey in Inflation Expectations" by Gwangmin Kim and Carola Binder.

Aggregated across months, the difference in expected CPI between these two groups is statistically different at the 5 percent level. However, the significance varies by month. At the height of the difference (July 2022), the difference was significant at the 10 percent level, while the difference in October 2023 is not significant. (Note that sample sizes can be small. In July 2022, 103 respondents who responded to the CPI question followed inflation somewhat closely, and 71 respondents followed inflation very closely.)

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Schwartzman, Felipe; and Waddell, Sonya Ravindranath. (January 2024) "Inflation Expectations and Price Setting Among Firms in the Fifth District." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 24-03.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.