Economic Effects Everywhere All at Once

Key Takeaways

- GDP growth and inflation are highly correlated across countries.

- Economic shocks in the U.S. have substantial effects globally.

- These spillovers are generated by multilateral linkages through trade in goods and assets.

The recent tariffs have brought global trade linkages to the forefront of academic and policy discussions. The global swings in the stock market and sentiment measures have emphasized how U.S. economic policy and conditions have important implications internationally.

This global interconnectedness has been present for decades and spurred much academic research even prior to recent developments. Indeed, output and inflation have moved in parallel across countries for many years now. While economists continue to analyze and quantify the sources of this comovement, cross-country linkages are clearly an important factor in driving economic fluctuations in each country. In this article, we examine the interconnectedness of countries' economies and what drives this comovement.

GDP Growth and Inflation in Different Countries Move Together

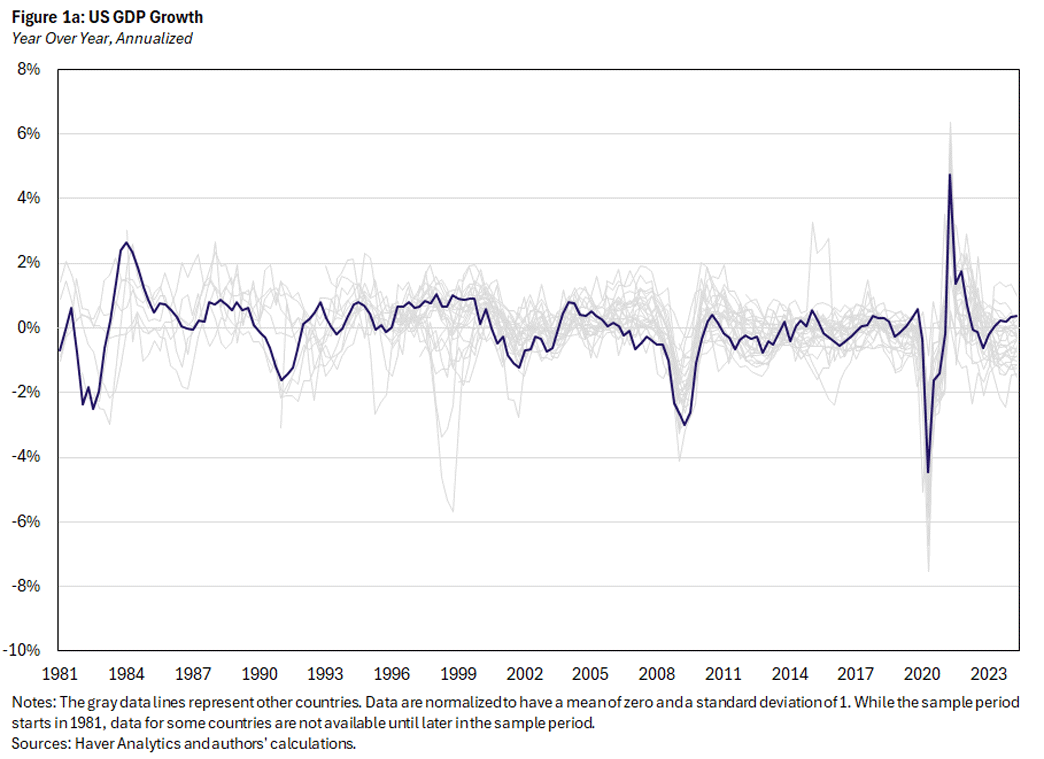

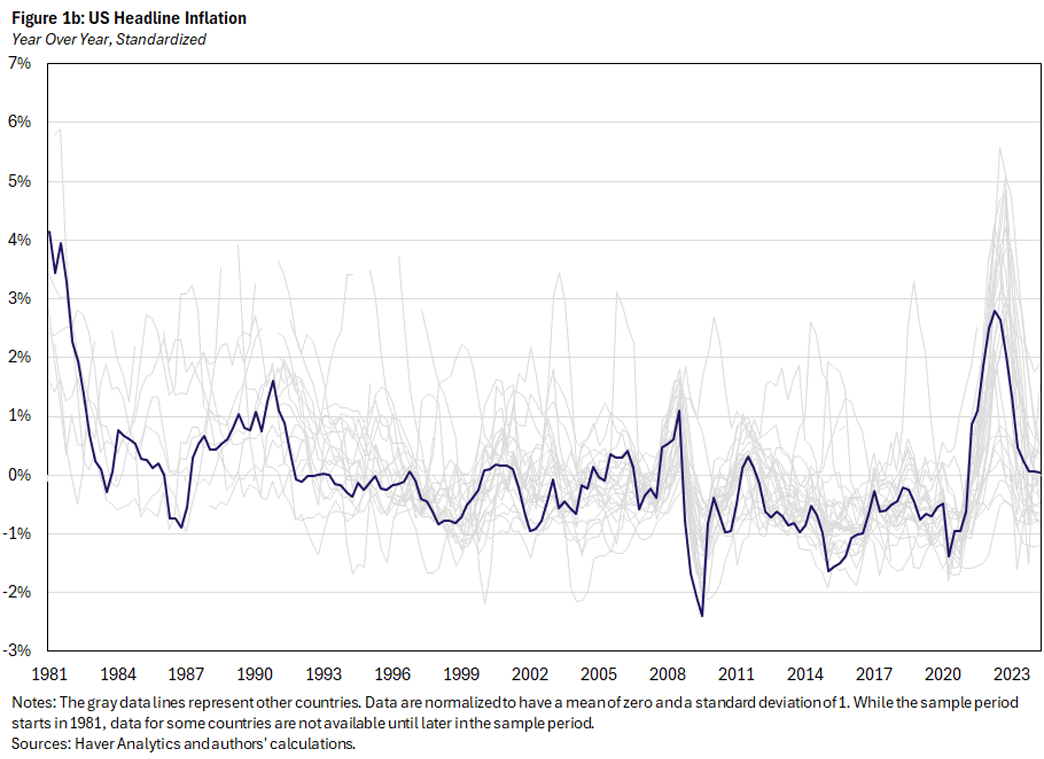

Figure 1 shows how U.S. GDP growth and inflation comove with 27 other countries. We plot quarterly data for year-over-year real GDP growth (Figure 1a) and inflation (Figure 1b) in each country, normalized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1 after trimming the data to remove hyperinflationary periods, thus making countries comparable regardless of their average growth rates or volatility. The sample period starts in the first quarter of 1981, but data for a number of countries are only available later in the sample.

The U.S. tends to move in parallel with other countries, with average correlations of 0.6 and 0.5 for GDP growth and inflation, respectively. The other countries also tend to comove with each other, with average correlations of 0.5 and 0.3 for GDP growth and inflation, respectively. While the comovement is most striking during the Great Recession and COVID-19 periods, it is also visible during the rest of the sample period.

The correlations are especially notable since consumption and production in many large economies are still predominantly domestic. For instance, U.S. exports and imports averaged 10.4 percent and 13.1 percent of total GDP, respectively, during this time.

Moreover, the cross-country correlations are large not just for countries that trade substantially with each other but also for seemingly less connected countries. For instance, while the U.S. and Canada have correlations of 0.46 and 0.76 for quarter-over-quarter GDP growth and inflation, respectively, the U.S. and Portugal have correlations of 0.27 and 0.50 despite U.S. exports and imports constituting only 2.3 and 1.0 percent of Portugal's GDP, respectively. Overall, the (log of) the import and export shares do not predict the bilateral correlations in GDP growth or inflation.

Country-Specific Shocks Propagate Across Borders

The above discussion is silent on how the comovement is generated. Given the pervasiveness of the comovement — including between countries with seemingly weaker trade linkages — one might think that the comovement must be explained by global shocks, such as global improvement in technology. However, this does not preclude the importance of spillovers of country-specific shocks.

A prominent example is the range of empirical estimates of how foreign economies respond to U.S. monetary policy surprises.1 Broadly speaking, the literature finds that a contractionary monetary policy shock in the U.S. leads to a decline in output globally that is between roughly one-third to one-half of the U.S. domestic production response.

The Global Trade Network Amplifies Spillovers

My (Paul's) working paper "Multilateral Comovement in a New Keynesian World: A Little Trade Goes a Long Way (PDF)" — co-authored with Pierre-Daniel Sarte and Felipe Schwartzman — shows how the multilateral trade network is crucial for generating spillovers and, thus, comovement across countries. In fact, we estimate that trade explains 90 percent of the cross-country comovement in GDP growth and almost 60 percent of the cross-country comovement in inflation. Since countries are connected through a broader trade network, their bilateral trade ties alone don't capture the spillovers one country could experience due to what happens in another country.

As an example, suppose demand falls in China. Since China imports some of its goods, demand will fall not only for Chinese goods but also for goods outside China. This will directly affect U.S. firms that export to China. However, it will also have indirect effects. Demand in China for European goods will fall, reducing their prices. All else equal, the reduction in European prices will lead to other countries to substitute away from U.S. goods and purchase more European goods instead. These effects occur ad infinitum through the global trade network, causing the initial shock in China to propagate more broadly around the world. Our paper shows that these indirect effects are quantitatively important for the observed comovement. Linkages between sectors across the production network further amplify these effects.

In the recent context of tariffs, the importance of the trade network emphasizes that bilateral trade tariffs between a pair of countries have the potential to have global effects. If a trade war between the U.S. and China leads to decline in demand for Chinese goods, the subsequent effects will spread to other countries, which will also affect the U.S. economy. When the two economies in question are as large as the U.S. and China, these concerns become more pertinent. The supply chain crunches during COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent inflationary episode are further recent evidence that economic disturbances in one country can have wide-ranging effects globally, as factory closures in China and Japan were acutely felt both in Asia and in the U.S.

Financial Conditions Are Also Correlated With the Global Business Cycle

An alternative explanation for the global comovement is the "global financial cycle" hypothesis.2 This hypothesis suggests that risky asset prices move together internationally, accompanied by movements in other financial variables (such as measures of risk aversion). A global decline in financial conditions is then associated with a decline in world production.

The roles of the goods and financial markets are not mutually exclusive. On the one hand, financial markets respond to conditions in the real economy. If trade in goods leads to spillovers in a domestic shock, the individual reactions of foreign financial markets will lead to a positive correlation across countries. On the other hand, financial markets themselves are globally integrated. Financial institutions invest internationally and lend to and borrow from each other. Consequently, when financial markets in one country are hit, the effects are felt in financial markets elsewhere. Moreover, the multilateral connections potentially generate the type of network effects described above for international goods markets.

The tight connection between financial variables and global economic conditions has become particularly salient recently, with large swings in financial markets in reaction to news about tariffs. For example, the S&P 500 Index fell by over 10 percent within the two days following April 2 but returned close to its original level by April 29. The Nikkei stock market index in Japan faced similar movement over that period. While these financial market fluctuations can be explained as responses to trade tariffs, the resulting stress on the financial sector can have its own real effects, as evidenced by the Great Recession, which itself generated reverberations globally.

Conclusion

We live in a globally connected economy. If this was not already clear in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been reiterated by the reactions of markets and firm survey participants. We further risk underestimating spillovers if we focus only on bilateral relationships and ignore the network effects generated by multilateral connections.

Katie Anderson and Nathan Robino are research associates and Paul Ho is a senior economist, all in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See, for example, the book chapter "The Global Financial Cycle" by Silvia Miranda-Agrippino and Helene Rey from the 2022 Handbook of International Economics and the book chapter "The International Monetary Transmission Mechanism" by Santiago Camara, Lawrence Christiano and Hüsnü Dalgic from the NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2024.

This is discussed in the previously cited book chapter "The Global Financial Cycle."

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Anderson, Katie; Ho, Paul; and Robino, Nathan. (June 2025) "Economic Effects Everywhere All at Once." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-25.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.