Oil Is Not Well in the World

As this blog post goes online, a horrific war continues to rage in Ukraine, inflicting tremendous suffering on the Ukranian people. Our thoughts are with them during this time.

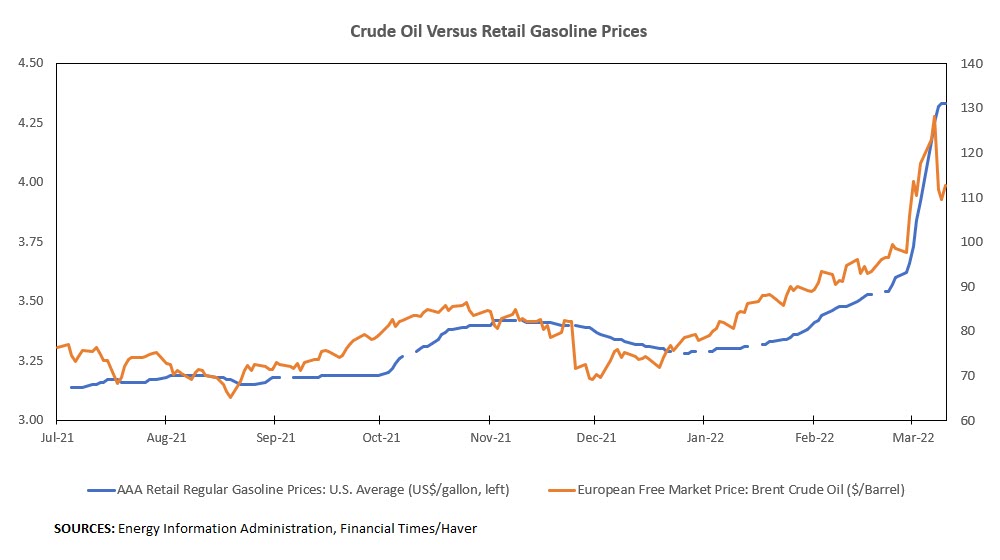

Given the interlinkages in today's global economy, the conflict has ripple effects that can be felt closer to home. Global crude oil prices have spiked following Russia's invasion, sending retail gasoline prices in the United States higher too. (See Figure 1 below.)

These higher gasoline prices will lift overall inflation, coming at a time when energy price inflation is already rising. For example, in February's CPI release, which doesn't yet fully reflect the Ukraine shock, energy prices rose 3.5 percent monthly compared to a 0.9 percent increase in January and are 25.7 percent higher than they were a year ago.

But are conflict-related disruptions responsible for all of the price pressures? The answer seems to be "no."

"Relative Price Changes Are Unlikely to Account for Recent High Inflation," Economic Brief No. 22-10, March 2022

"Are Firms Factoring Increasing Inflation Into Their Prices?" Economic Brief No. 22-08, March 2022

As described in the U.S. Energy Information Administration's March 2022 Short Term Energy Outlook, there are a number of preexisting conditions at play. Several members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries have been unable to increase production in line with their announced targets. Port closures and conflict in the Middle East have disrupted oil supply. Oil consumption has exceeded production since mid-2020, while total commercial oil inventories in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries have fallen to their lowest levels since mid-2014.

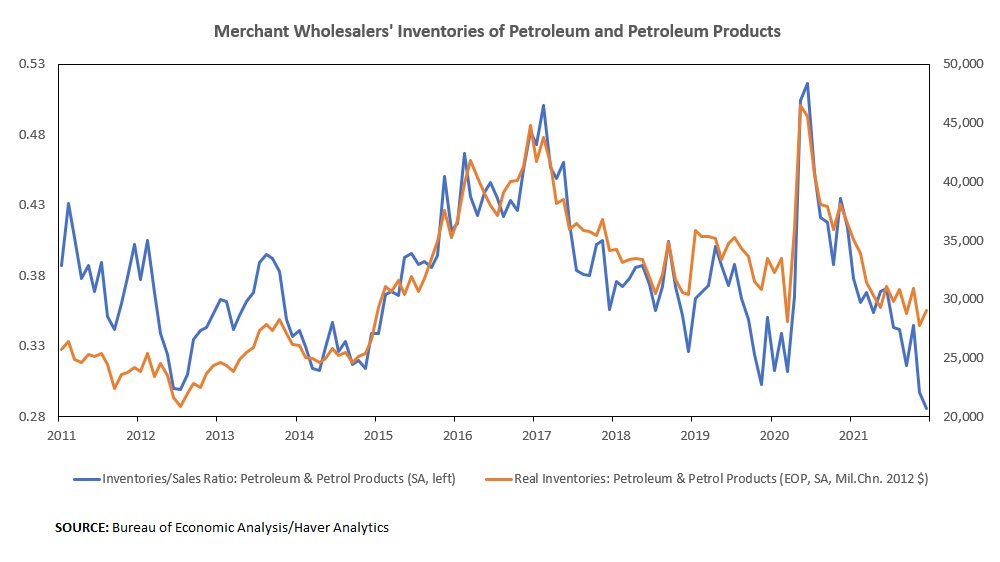

Despite being an oil producer, the United States has seen similar inventory behavior. As depicted in Figure 2 below, as of December 2021, merchant wholesalers' real inventories of petroleum and petroleum products are 13 percent lower than their pre-pandemic level. The corresponding inventory-to-sales ratio has dropped to its lowest level in at least a decade, extending a declining trend in inventory-to-sales that goes back three years before the pandemic.

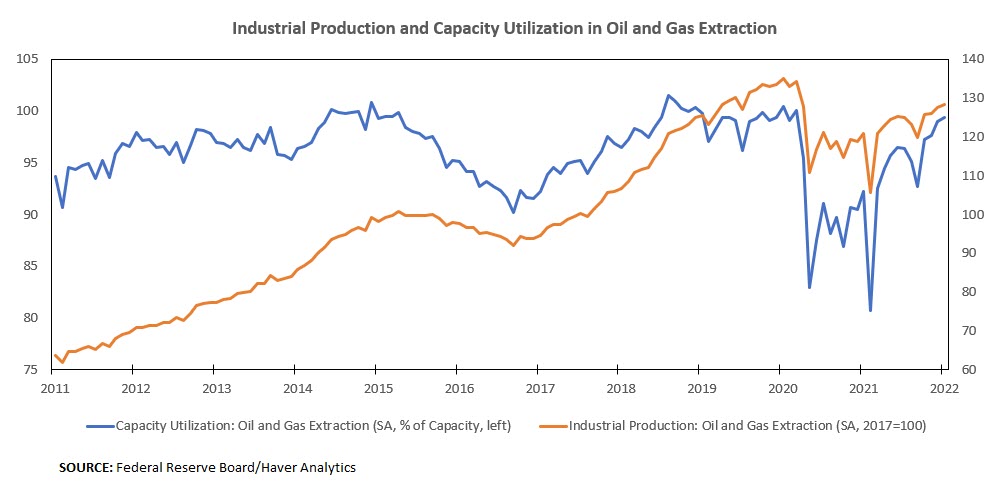

Could the United States step up its production to fill in any supply gaps and minimize any disruption? In the short run, it wouldn't be easy.

As of January, the industrial production index for oil and gas extraction is 4 percent lower than it was prior to the pandemic, which might suggest the industry has room to raise its output. However, as shown in Figure 3 below, capacity utilization in January was 99.3 percent, slightly higher than its February 2020 level of 99.1 percent. That, along with data on rig counts, suggests oil production capacity has been taken offline since the start of the pandemic. Thus, in the short term it will be difficult to squeeze out more production at existing levels of capacity.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.