A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages

Americans take today's selection of mortgages for granted, but financing a home is a much different experience than it was a century ago

The furniture industry was booming in Greensboro, N.C., 100 years ago. A furniture craftsman making a solid, steady income might have wanted to buy a home and build up some equity. But the homebuying process then looked very little like it does today. To finance that purchase, the furniture maker first would need to scrape together as much as 40 percent for a down payment, even with good credit. He might then head to a local building and loan association (B&L), where he would hope to get a loan that he would be able to pay off in no more than a dozen years.

Today's mortgage market, by contrast, would offer that furniture maker a wide range of more attractive options. Instead of going to the local B&L, the furniture maker could walk into a bank or connect with a mortgage broker who could be in town or on the other side of the country. No longer would such a large down payment be necessary; 20 percent would suffice, and it could be less with mortgage insurance — even zero dollars down if the furniture maker were also a veteran. Further, the repayment period would be set at either 15 or 30 years, and, depending on what worked best for the furniture maker, the interest rate could be fixed or fluctuate through the duration of the loan.

The modern mortgage in all its variations is the product of a complicated history. Local, state, national, and even international actors all competing for profits have existed alongside an increasingly active federal government that for almost a century has sought to make the benefits of homeownership accessible to more Americans, even through economic collapse and crises. Both despite and because of this history, over 65 percent of Americans — most of whom carry or carried a mortgage previously — now own the home where they live.

The Early Era of Private Financing

Prior to 1930, the government was not involved in the mortgage market, leaving only a few private options for aspiring homeowners looking for financing. While loans between individuals for homes were common, building and loan associations would become the dominant institutional mortgage financiers during this period.

B&Ls commonly used what was known as a "share accumulation" contract. Under this complicated mortgage structure, if a borrower needed a loan for $1,000, he would subscribe to the association for five shares at $200 maturity value each, and he would accumulate those shares by paying weekly or monthly installments into an account held at the association. These payments would pay for the shares along with the interest on the loan, and the B&L would also pay out dividends kept in the share account. The dividends determined the duration of the loan, but in good economic times, a borrower would expect it to take about 12 years to accumulate enough money through the dividends and deposits to repay the entire $1,000 loan all at once; he would then own the property outright.

An import from a rapidly industrializing Great Britain in the 1830s, B&Ls had been operating mainly in the Northeast and Midwest until the 1880s, when, coupled with a lack of competition and rapid urbanization around the country, their presence increased significantly. In 1893, for example, 5,600 B&Ls were in operation in every state and in more than 1,000 counties and 2,000 cities. Some 1.4 million Americans were members of B&Ls and about one in eight nonfarm owner-occupied homes was financed through them. These numbers would peak in 1927, with 11.3 million members (out of a total population of 119 million) belonging to 12,804 associations that held a total of $7.2 billion in assets.

Despite their popularity, B&Ls had a notable drawback: Their borrowers were exposed to significant credit risk. If a B&L's loan portfolio suffered, dividend accrual could slow, extending the amount of time it would take for members to pay off their loans. In extreme cases, retained dividends could be taken away or the value of outstanding shares could be written down, taking borrowers further away from final repayment.

"Imagine you are in year 11 of what should be a 12-year repayment period and you've borrowed $2,000 and you've got $1,800 of it in your account," says Kenneth Snowden, an economist at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, "but then the B&L goes belly up. That would be a disaster."

The industry downplayed the issue. While acknowledging that "It is possible in the event of failure under the regular [share accumulation] plan that … the borrower would still be liable for the total amount of his loan," the authors of a 1925 industry publication still maintained, "It makes very little practical difference because of the small likelihood of failure."

Aside from the B&Ls, there were few other institutional lending options for individuals looking for mortgage financing. The National Bank Act of 1864 barred commercial banks from writing mortgages, but life insurance companies and mutual savings banks were active lenders. They were, however, heavily regulated and often barred from lending across state lines or beyond certain distances from their location.

But the money to finance the building boom of the second half of the 19th century had to come from somewhere. Unconstrained by geographic boundaries or the law, mortgage companies and trusts sprouted up in the 1870s, filling this need through another innovation from Europe: the mortgage-backed security (MBS). One of the first such firms, the United States Mortgage Company, was founded in 1871. Boasting a New York board of directors that included the likes of J. Pierpont Morgan, the company wrote its own mortgages, and then issued bonds or securities that equaled the value of all the mortgages it held. It made money by charging interest on loans at a greater rate than what it paid out on its bonds. The company was vast: It established local lending boards throughout the country to handle loan origination, pricing, and credit quality, but it also had a European-based board comprised of counts and barons to manage the sale of those bonds on the continent.

During the 1930s, the building and loan associations began to evolve into savings and loan associations (S&L) and were granted federal charters. As a result, these associations had to adhere to certain regulatory requirements, including a mandate to make only fully amortized loans and caps on the amount of interest they could pay on deposits. They were also required to participate in the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), which, in theory, meant that their members' deposits were guaranteed and would no longer be subject to the risk that characterized the pre-Depression era.

The B&Ls and S&Ls vehemently opposed the creation of the FHA, as it both opened competition in the market and created a new bureaucracy that they argued was unnecessary. Their first concern was competition. If the FHA provided insurance to all institutional lenders, the associations believed they would no longer dominate the long-term mortgage loan market, as they had for almost a century. Despite intense lobbying in opposition to the creation of the FHA, the S&Ls lost that battle, and commercial banks, which had been able to make mortgage loans since 1913, ended up making by far the biggest share of FHA-insured loans, accounting for 70 percent of all FHA loans in 1935. The associations also were loath to follow all the regulations and bureaucracy that were required for the FHA to guarantee loans.

"The associations had been underwriting loans successfully for 60 years. FHA created a whole new bureaucracy of how to underwrite loans because they had a manual that was 500 pages long," notes Snowden. "They don't want all that red tape. They don't want someone telling them how many inches apart their studs have to be. They had their own appraisers and underwriting program. So there really were competing networks."

As a result of these two sources of opposition, only 789 out of almost 7,000 associations were using FHA insurance in 1940.

In 1938, the housing market was still lagging in its recovery relative to other sectors of the economy. To further open the flow of capital to homebuyers, the government chartered the Federal National Mortgage Association, or Fannie Mae. Known as a government sponsored-enterprise, or GSE, Fannie Mae purchased FHA-guaranteed loans from mortgage lenders and kept them in its own portfolio. (Much later, starting in the 1980s, it would sell them as MBS on the secondary market.)

The Postwar Homeownership Boom

In 1940, about 44 percent of Americans owned their home. Two decades later, that number had risen to 62 percent. Daniel Fetter, an economist at Stanford University, argued in a 2014 paper that this increase was driven by rising real incomes, favorable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing, and perhaps most importantly, the widespread adoption of the long-term, fully amortized, low-down-payment mortgage. In fact, he estimated that changes in home financing might explain about 40 percent of the overall increase in homeownership during this period.

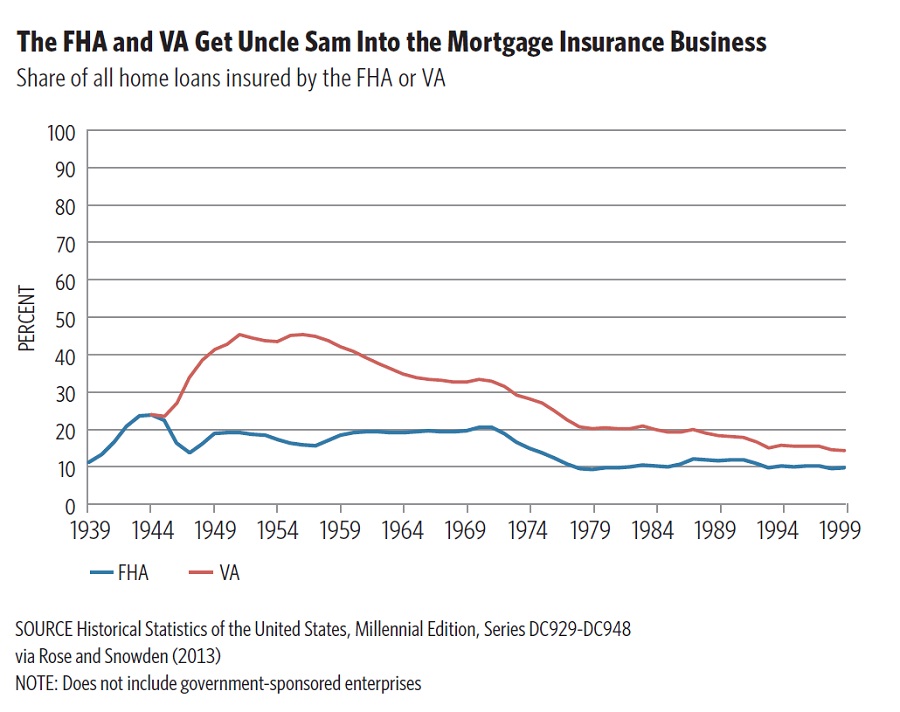

One of the primary pathways for the expansion of homeownership during the postwar period was the veterans' home loan program created under the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act. While the Veterans Administration (VA) did not make loans, if a veteran defaulted, it would pay up to 50 percent of the loan or up to $2,000. At a time when the average home price was about $8,600, the repayment window was 20 years. Also, interest rates for VA loans could not exceed 4 percent and often did not require a down payment. These loans were widely used: Between 1949 and 1953, they averaged 24 percent of the market and according to Fetter, accounted for roughly 7.4 percent of the overall increase in homeownership between 1940 and 1960. (See chart below.)

Demand for housing continued as baby boomers grew into adults in the 1970s and pursued homeownership just as their parents did. Congress realized, however, that the secondary market where MBS were traded lacked sufficient capital to finance the younger generation's purchases. In response, Congress chartered a second GSE, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, also known as Freddie Mac. Up until this point, Fannie had only been authorized to purchase FHA-backed loans, but with the hope of turning Fannie and Freddie into competitors on the secondary mortgage market, Congress privatized Fannie in 1968. In 1970, they were both also allowed to purchase conventional loans (that is, loans not backed by either the FHA or VA).

A Series of Crises

A decade later, the S&L industry that had existed for half a century would collapse. As interest rates rose in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the S&Ls, also known as "thrifts," found themselves at a disadvantage, as the government-imposed limits on their interest rates meant depositors could find greater returns elsewhere. With inflation also increasing, the S&Ls' portfolios, which were filled with fixed-rate mortgages, lost significant value as well. As a result, many S&Ls became insolvent.

Normally, this would have meant shutting the weak S&Ls down. But there was a further problem: In 1983, the cost of paying off what these firms owed depositors was estimated at about $25 billion, but FSLIC, the government entity that ensured those deposits, had only $6 billion in reserves. In the face of this shortfall, regulators decided to allow these insolvent thrifts, known as "zombies," to remain open rather than figure out how to shut them down and repay what they owed. At the same time, legislators and regulators relaxed capital standards, allowing these firms to pay higher rates to attract funds and engage in ever-riskier projects with the hope that they would pay off in higher returns. Ultimately, when these high-risk ventures failed in the late 1980s, the cost to taxpayers, who had to cover these guaranteed deposits, was about $124 billion. But the S&Ls would not be the only actors in the mortgage industry to need a taxpayer bailout.

By the turn of the century, both Fannie and Freddie had converted to shareholder-owned, for-profit corporations, but regulations put in place by the Federal Housing Finance Agency authorized them to purchase from lenders only so-called conforming mortgages, that is, ones that satisfied certain standards with respect to the borrower's debt-to-income ratio, the amount of the loan, and the size of the down payment. During the 1980s and 1990s, their status as GSEs fueled the perception that the government — the taxpayers — would bail them out if they ever ran into financial trouble.

Developments in the mortgage marketplace soon set the stage for exactly that trouble. The secondary mortgage market in the early 2000s saw increasing growth in private-label securities — meaning they were not issued by one of the GSEs. These securities were backed by mortgages that did not necessarily have to adhere to the same standards as those purchased by the GSEs.

"Mortgage Refinance Costs and a Better Adjustable-Rate Mortgage Contract." Economic Brief No. 21-38, November 2021.

"Federal Reserve MBS Purchases in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic." Economic Brief No. 20-08, July 2020.

"The First Time the Fed Bought GSE Debt." Economic Brief No. 14-04, April 2014.

Freddie and Fannie, as profit-seeking corporations, were then under pressure to increase returns for their shareholders, and while they were restricted in the securitizations that they could issue, they were not prevented from adding these riskier private-label MBS to their own investment portfolios.

At the same time, a series of technological innovations lowered the costs to the GSEs, as well as many of the lenders and secondary market participants, of assessing and pricing risk. Beginning back in 1992, Freddie had begun accessing computerized credit scores, but more extensive systems in subsequent years captured additional data on the borrowers and properties and fed that data into statistical models to produce underwriting recommendations. By early 2006, more than 90 percent of lenders were participating in an automated underwriting system, typically either Fannie's Desktop Underwriter or Freddie's Loan Prospector (now known as Loan Product Advisor).

Borys Grochulski of the Richmond Fed observes that these systems made a difference, as they allowed lenders to be creative in constructing mortgages for would-be homeowners who would otherwise be unable to qualify. "Many potential mortgage borrowers who didn't have the right credit quality and were out of the mortgage market now could be brought on by these financial-information processing innovations," he says.

Indeed, speaking in May 2007, before the full extent of the impending mortgage crisis — and Great Recession — was apparent, then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke noted that the expansion of what was known as the subprime mortgage market was spurred mostly by these technological innovations. Subprime is just one of several categories of loan quality and risk; lenders used data to separate borrowers into risk categories, with riskier loans charged higher rates.

But Marc Gott, a former director of Fannie's Loan Servicing Department said in a 2008 New York Times interview, "We didn't really know what we were buying. This system was designed for plain vanilla loans, and we were trying to push chocolate sundaes through the gears."

Nonetheless, some investors still wanted to diversify their portfolios with MBS with higher yields. And the government's implicit backing of the GSEs gave market participants the confidence to continue securitizing, buying, and selling mortgages until the bubble finally popped in 2008. (The incentive for such risk taking in response to the expectation of insurance coverage or a bailout is known as "moral hazard.")

According to research by the Treasury Department, 8 million homes were foreclosed, 8.8 million workers lost their jobs, and $7.4 trillion in stock market wealth and $19.2 trillion in household wealth was wiped away during the Great Recession that followed the mortgage crisis. As it became clear that the GSEs had purchased loans they knew were risky, they were placed under government conservatorship that is still in place, and they ultimately cost taxpayers $190 billion. In addition, to inject liquidity into the struggling mortgage market, the Fed began purchasing the GSEs' MBS in late 2008 and would ultimately purchase over $1 trillion in those bonds up through late 2014.

The 2008 housing crisis and the Great Recession have made it harder for some aspiring homeowners to purchase a home, as no-money-down mortgages are no longer available for most borrowers, and banks are also less willing to lend to those with less-than-ideal credit. Also, traditional commercial banks, which also suffered tremendous losses, have stepped back from their involvement in mortgage origination and servicing. Filling the gap has been increased competition among smaller mortgage companies, many of whom, according to Grochulski, sell their mortgages to the GSEs, who still package them and sell them off to the private markets.

While the market seems to be functioning well now under this structure, stresses have been a persistent presence throughout its history. And while these crises have been painful and disruptive, they have fueled innovations that have given a wide range of Americans the chance to enjoy the benefits — and burdens — of homeownership.

READINGS

Brewer, H. Peers. "Eastern Money and Western Mortgages in the 1870s." Business History Review, Autumn 1976, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 356-380.

Fetter, Daniel K. "The Twentieth-Century Increase in U.S. Home Ownership: Facts and Hypotheses." In Eugene N. White, Kenneth Snowden, and Price Fishback (eds.), Housing and Mortgage Markets in Historical Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, July 2014, pp. 329-350.

McDonald, Oonagh. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Turning the American Dream into a Nightmare. New York, N.Y.: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012.

Price, David A., and John R. Walter. "It's a Wonderful Loan: A Short History of Building and Loan Associations," Economic Brief No. 19-01, January 2019.

Romero, Jessie. "The House Is in the Mail." Econ Focus, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Second/Third Quarter 2019.

Rose, Jonathan D., and Kenneth A. Snowden. "The New Deal and the Origins of the Modern American Real Estate Contract." Explorations in Economic History, October 2013, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 548-566.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.