Central Bank Lending Lessons from the 2023 Bank Crisis

The Fed moved quickly to support the financial system during a banking panic last spring. Now, policymakers are evaluating what they learned.

In the spring of 2023, a pair of fast-moving bank runs threatened to spark a widespread financial panic. On March 9, the 16th largest bank in the country, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in Santa Clara, Calif., lost a quarter of its deposits in a single day. It was set to lose another 62 percent of deposits the following day before it was closed by regulators. On March 10, New York-based Signature Bank experienced a similarly rapid flight of 20 percent of its deposits. It was closed by regulators on March 12.

At the time of their collapses, SVB ($209 billion in assets) and Signature Bank ($110 billion in assets) were the second- and third-largest bank failures in U.S. history. Their failures were also exceptionally quick by modern standards. By comparison, Washington Mutual, the largest bank failure in American history, lost 10 percent of its deposits over the course of 16 days in September 2008.

The business models of SVB and Signature Bank differed, but both were hit by rapidly rising interest rates following the post-pandemic surge in inflation. Both also had a large share of institutional depositors with accounts that exceeded the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insurance limit of $250,000, making the depositors more likely to withdraw funds at signs of trouble. The rapid failures of SVB and Signature Bank raised concerns that other banks with similar risks might soon follow.

The Crisis and Response

In the days surrounding the failures of SVB and Signature Bank, depositors fled banks with assets between $50 billion and $250 billion, moving their money primarily to larger institutions. According to a May 2024 paper by Marco Cipriani and Thomas Eisenbach of the New York Fed and Anna Kovner, research director of the Richmond Fed, a total of 22 banks experienced runs last March.

The turmoil would ultimately claim one more victim, First Republic Bank in San Francisco, which began experiencing a run on March 10 and failed on May 1. With $213 billion in assets, it took the number two slot on the list of largest bank failures, surpassing SVB. According to a report from the Group of Thirty, an independent global body of economic leaders and experts who advise on issues facing policymakers and market participants, the three failed banks collectively held more assets than all bank assets lost in the 2008 financial crisis.

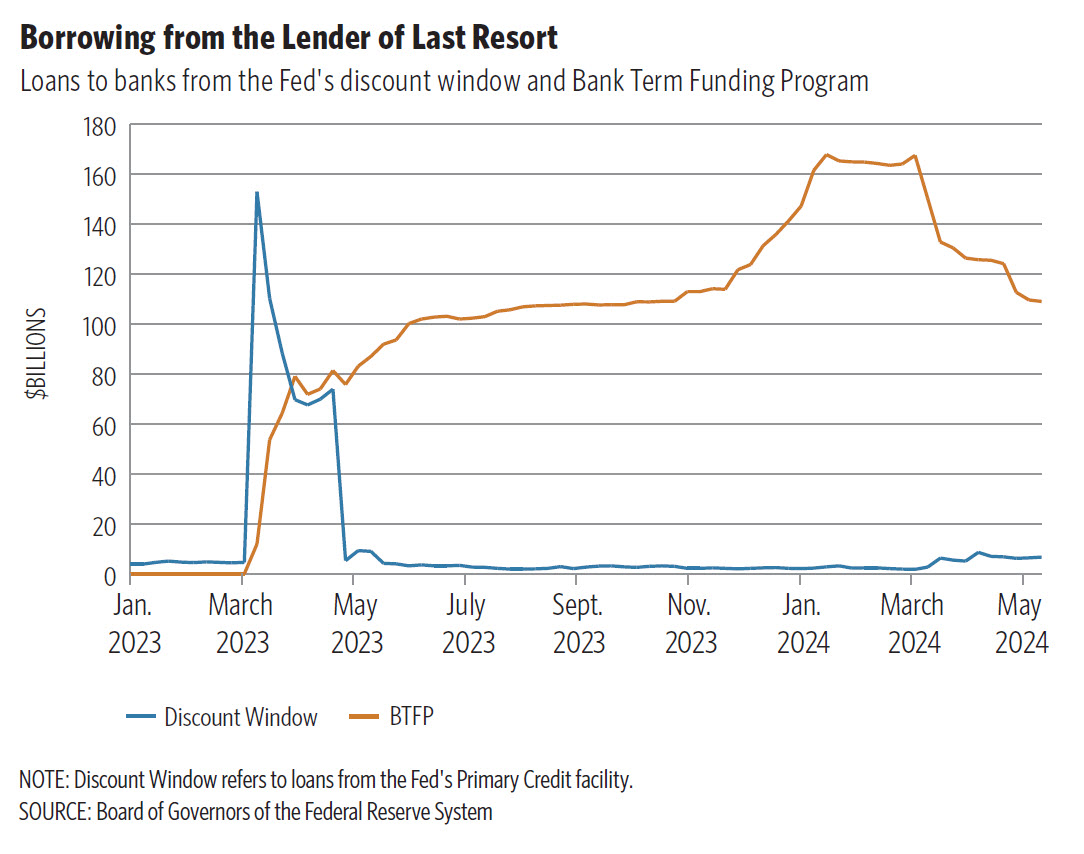

As in that previous crisis, the Fed acted swiftly to prevent financial turmoil from sweeping up other institutions. Borrowing at the Fed's discount window, a standing facility that makes short-term loans to qualified banks, spiked from $4.6 billion on March 9 to $152.9 billion on March 15. The Fed also created an additional lending facility on March 12 to support the financial system: the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). Through the BTFP, the Fed made loans to banks in exchange for government bonds and agency securities as collateral. (See chart.)

These actions fulfilled one of the Fed's oldest functions: to serve as a "lender of last resort" to the financial system. Partly thanks to this intervention, widespread failures were averted despite many banks experiencing significant stress. In the year since, Fed policymakers and academic researchers have been examining the events of last March for lessons on how to improve the central bank's lender-of-last-resort facilities before the next crisis.

Role of the Lender of Last Resort

By the nature of their business, banks are susceptible to panics. They take customer deposits, which can be withdrawn on demand, and invest in longer-duration assets like loans. Such assets are often held to maturity and may not be easy to sell quickly. If too many depositors seek to withdraw their money at once, a bank may not have enough cash to meet the sudden surge in demand. This can lead to a run, as depositors rush to get their money out while the bank still has funds to pay them.

Financial regulators have sought to ensure that banks are resilient against runs by requiring them to hold enough capital to absorb losses as well as enough liquid assets to meet a sudden surge in depositor demand. These precautions must be balanced against the fact that requiring banks to raise more capital and hold more cash could limit their capacity to make loans and channel credit to productive uses in the economy.

When a crisis eventually comes, solvent but temporarily illiquid banks can borrow from the Fed to weather the storm. Even if central bank lending doesn't ultimately prevent a bank's failure, it can avert the need for the bank to sell assets at fire-sale prices to meet depositor demand. Such sales can fan the flames of the financial panic by devaluing the assets held by other institutions, potentially bringing the run to their doors as well. Having an entity to play this role in the U.S. economy was a major motivation for the creation of the Fed in 1913. In the mid-19th and early 20th century, when America had no central bank, banking crises were frequent occurrences.

The discount window has been the Fed's primary lender-of-last-resort tool since its founding. Banks pledge collateral — which can include loans, bonds, and other asset-backed securities — and the Fed determines the amount of money the bank can borrow. (This is typically the value of the collateral minus a haircut.) While this facility was created to help the banking system in an emergency, historically banks have been reluctant to use it even in a crisis.

That's because borrowing from the lender of last resort is often interpreted as a sign that a bank has exhausted all other options. Many bankers worry that sending such a signal could further intensify pressures for a run by revealing the bank is in a weaker condition than its depositors may have realized. At a March event hosted by the Brookings Institution's Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, William Demchak, the CEO of PNC Financial Services Group, remarked, "The day you hit it [the discount window] for anything other than a test you effectively have told the world you failed."

The Stigma Challenge

Banks that borrow from the discount window, then, would prefer to keep that fact a secret. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 requires the Fed to disclose the identities of discount window borrowers after a two-year lag. In theory, the revelation should come long after the crisis has passed. But in practice, market participants can often infer the identities of discount window borrowers much sooner.

The Fed publishes weekly data disclosing the assets and liabilities of each Reserve Bank — including discount window loans. Banks borrowing from the discount window do so at their regional Reserve Bank. A spike in lending at one of the 12 Federal Reserve districts can therefore provide a clue about which banks might have borrowed based on where they are headquartered. In 2020, the Fed made some modifications to how it reports this data to further mask individual banks' discount window activity. But in an April article, Steven Kelly, the associate director of research at the Yale Program on Financial Stability, argued that it is often still possible to detect a spike in certain borrowers' discount window use from the weekly reports.

"The Fed's data does offer some degree of obfuscation, but not enough," says Kelly. "The way that data is set up, it's the mid-sized and larger banks that are most vulnerable to being revealed. So when you have a crisis primarily among mid-sized banks, like we did in March 2023, there was a very real fear of tapping the discount window and being discovered by the market."

In part because of this stigma, banks have often turned to alternative sources of emergency credit, including other Fed facilities. During the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the Fed created the Term Auction Facility (TAF) as an alternative program for making loans to banks. Unlike discount window loans, the rates on TAF loans were determined by auction. This auction design may have made it more difficult for the market to deduce the identity of borrowers, reducing the stigma banks faced when borrowing from the Fed.

A Lender of Next-to-Last Resort

Created by Congress in 1932, the FHLB system was set up to provide funding for mortgage lenders to support the housing market during the Great Depression. There are 11 FHLBs that each serve a particular region. Depository institutions can become a member of their regional FHLB and receive loans (called advances) in exchange for eligible collateral. While FHLB advances were originally intended to support housing, banks have used them as a source of general liquidity in times of financial crisis. This practice has led some to call the FHLB system a "lender of next-to-last resort."

In the lead-up to the 2023 banking crisis, SVB, First Republic, and Signature Bank all borrowed heavily from their FHLBs. According to a March report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, SVB and First Republic were the largest borrowers from the San Francisco FHLB at the start of the year, and Signature Bank was the fourth-largest borrower from the New York FHLB. All three banks sharply increased their borrowing and requests for FHLB advances in early March as they experienced distress. For example, the balance of FHLB advances to SVB increased by 50 percent — from $20 billion to $30 billion — between March 1 and March 8.

While having an additional lender of last resort during a crisis may seem like a good thing, researchers have identified some issues with the FHLBs playing this role. In principle, FHLBs make advances only to sound institutions in exchange for good collateral. But in practice, they may not always have the strongest incentives to assess borrower soundness because their collateral requirements make it unlikely that they would lose money if the institution fails, according to Columbia University law professor Kathryn Judge.

In a May 2014 article in the Cornell Law Review, Judge wrote that "no FHLBank has ever lost money on an advance despite the failure of many banks with significant outstanding advances." If financial firms can obtain funding from the FHLBs that the market would otherwise not provide them, they can delay their reckoning until their ultimate failure is much larger and costlier to the financial system. This could contribute to excessive risk-taking by failing firms, which have a greater incentive to take on more risk to avoid failure.

Another problem identified by researchers is that, unlike the Fed, FHLBs need to raise funding from the market to issue advances. Since marketplace funding takes time to execute, the ability of FHLBs to lend could become constrained precisely when they are needed to act as a lender of last resort.

"The Federal Home Loan Banks simply aren't as capable emergency lenders as the Fed, particularly when it comes to large sums, because they have to raise the money," says Kelly. "FHLBs can also be procyclical in a way that the Fed is not. During crises, FHLBs have raised the haircuts they apply to collateral, or, as we saw in the case of First Republic, they may suddenly stop lending to a bank to figure out what is going on. Those are things that the Fed doesn't do."

A third challenge is that borrowing from FHLBs can complicate a bank's ability to also borrow from the Fed. When a bank borrows from the discount window, it needs to put up collateral without competing claims, allowing the Fed to seize it if the bank fails to repay the loan. When FHLBs issue advances, they impose a lien on the collateral that supersedes all other claims, making it ineligible for use at the discount window. This can be cleared up with discussions between the Fed and FHLBs, but in a fast-moving crisis there may not be enough time. In the case of Signature Bank, FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg said in congressional testimony that these issues were only resolved with "minutes to spare before the Federal Reserve's wire room closed."

Speed and Readiness

The speed of the March 2023 crisis also revealed important lessons for policymakers. In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007-2008, regulators introduced a new requirement known as a Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which requires banks of a certain size to hold highly liquid assets proportionate to their total assets. (See "Liquidity Requirements and the Lender of Last Resort," Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2015.) The LCR presumes that during a run, between 25 percent and 40 percent of a bank's large uninsured deposits could flee over the course of a month.

"With SVB, we saw the attempted withdrawal of over 60 percent of deposits in one day," says Darrell Duffie, a professor of management and finance at Stanford University. "It is clear now, if it wasn't before, that large uninsured depositors will move their funds out of a bank that's in trouble very quickly, particularly financially savvy large depositors who are going to be attuned to these risks."

"Perspectives on the Banking Turmoil of 2023," Economic Brief No. 23-35, October 2023

"Who Borrows From the Discount Window in 'Normal' Times?" Economic Brief No. 21-09, March 2021

"Understanding Discount Window Stigma," Economic Brief No. 20-04, April 2020

Short of having enough liquidity on hand to meet such a rapid and large deposit flight, the 2023 crisis suggests the importance of banks being prepared to borrow from the lender of last resort at a moment's notice. All three banks that failed experienced difficulties borrowing from the discount window, in part due to a lack of practice with the requirements involved. SVB had not tested its ability to borrow from the discount window at all in 2022, and Signature Bank had not conducted such tests in the five years before its failure.

In a 2021 Richmond Fed Economic Brief, Ennis found that in the noncrisis period of 2010-2017, very few institutions with less than $1 billion in assets borrowed from the Fed's discount window: only 7 percent of domestic banks and 2 percent of credit unions. Starting this year, the Fed has begun releasing annual statistics on banks' and credit unions' readiness to borrow from the discount window. Between 2022 and 2023, the number of institutions signed up to use the discount window increased by 9.4 percent, from 4,952 to 5,418. Ennis says that to the extent that the events of March 2023 revealed that banks were not fully informed about the steps they needed to take to be ready to borrow quickly from the discount window, it is helpful for the Fed to share information and create greater awareness.

"At the same time, I would say that there should be no presumption that a bank needs to be able to borrow from the discount window," he says. "Banks need to make that determination themselves after considering all the relevant information."

Last year's crisis also cast a spotlight on the Fed's readiness to handle requests that could come at any time in the fast-paced era of modern finance. In a 2023 article, Yale Program of Financial Stability Executive Fellow Susan McLaughlin noted that there are different cutoff times for pledging collateral at the discount window to borrow that same day. These cutoff times can be as early as 9:15 a.m. Pacific Time depending on the type of securities being pledged, and two of the failed banks were located on the West Coast. This is why the Fed recommends that banks pre-position their collateral at the discount window to be ready to borrow right away in an emergency. In the wake of last year's crisis, some have called for this pre-positioning to be taken a step further.

Potential Reforms

A January report from the Group of Thirty's Working Group on the 2023 Banking Crisis, chaired by former New York Fed President William Dudley, recommended that the Fed require banks to pre-position enough collateral at the discount window to cover all their runnable liabilities, which would notably include all uninsured deposits.

"It would mitigate the risk of runs triggered merely because one depositor thinks other depositors are going to move," says Duffie, who was an adviser on the report.

Fed officials have indicated they are looking at such a change. In a May speech, Michael Barr, the vice chair for supervision on the Fed's Board of Governors, said the Fed was considering requiring banks to pre-position collateral at the discount window based on a fraction of their uninsured deposits.

Barr also acknowledged criticisms about the technology and procedures surrounding discount window borrowing and the need to reduce stigma. "Given the important role of the discount window, we're also actively working to improve its functionality," he said. In March, the Fed launched Discount Window Direct, an online portal qualified banks can use to access the facility.

All eyes will be on these and other reforms as the Fed (alongside other regulators) continues to explore ways to improve its oldest function before the next crisis.

Readings

"Bank Failures and Contagion: Lender of Last Resort, Liquidity, and Risk Management." G30 Working Group on the 2023 Banking Crisis, January 2024.

Cipriani, Marco, Thomas M. Eisenbach, and Anna Kovner. "Tracing Bank Runs in Real Time." Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports No. 1104, May 2024.

Kelly, Steven. "Weekly Fed Report Still Drives Discount Window Stigma." Yale School of Management Program on Financial Stability, April 3, 2024.

McLaughlin, Susan. "Lessons for the Discount Window from the March 2023 Bank Failures." Yale School of Management Program on Financial Stability, Sept. 19, 2023.

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.