Housing and Transportation

It's a common saying among housing policy experts that "houses are where jobs sleep at night."

This means that housing is critical not only for individuals, but also for employers. The Richmond Fed hears consistently from employers and local policymakers that insufficient housing poses a major challenge to recruiting and retaining the workers that are necessary to attract and keep employers in the area.

Housing availability and affordability are widely recognized as constraints in urban areas, but they are a concern in more rural areas as well, even though housing tends to be less expensive there. About a quarter of rural Fifth District households are "cost burdened" (defined as spending more than 30 percent of household income on housing), which is not much lower than the share of urban households that are housing cost burdened — about 28 percent. (See "Housing the Workforce in the Rural Fifth District," Econ Focus, First Quarter 2022.) This, too, varies by region, with counties closer to the coast tending to have higher rates of cost burden than counties further inland.

Access to housing is only part of the story — lower density means that a household's need to spend on transportation increases with rurality. In fact, rural households travel about 33 percent more than urban households. The typical rural household in the Fifth District spends nearly 32 percent of its income on transportation costs, compared to about 22 percent for urban households.

Housing and transportation represent the two largest expenses for the average household. According to the Center for Neighborhood Technology, a nonprofit research and advocacy group, housing and transportation expenses are considered affordable when they together account for no more than 45 percent of household income. The typical urban and rural household both exceed that threshold in the Fifth District, but the typical Fifth District rural household exceeds it to a much greater degree, spending around 60 percent of its income on housing and transportation expenses, compared to just under 50 percent for urban households.

Child Care Access and Affordability

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the labor market benefits of a well-functioning child care system. But providing access to formal child care (such as care centers or home-based child care) is challenging in rural areas with low population density. Providers might not want to expand their staffs or facilities if they are not confident that they will be able to enroll enough children to justify the additional cost. Thus, rural child care providers are more likely to underprovide child care service to their local community. Moreover, providers may be limited in their ability to locate their businesses to be convenient to families due to real estate constraints and costs associated with establishing a new child care facility. As a result, families in rural areas are more likely to have difficulty accessing affordable child care. Based on our analysis of the Center for American Progress' Child Care Desert data, 58 percent of rural children in the Fifth District live in a child care desert, compared to 55 percent of urban children and only 40 percent of suburban children. (Of course, there may be a demand-side issue as well. In a recent survey commissioned by the Bipartisan Policy Center, 35 percent of rural families said that their ideal care arrangement would be to provide care themselves, compared to 20 percent of urban families.)

For a child care system to be effective, it needs to be accessible, affordable, and high-quality. A report by the Fed's Early Care and Education Work Group, which includes the Richmond Fed's Erika Bell, the community development regional managing serving North Carolina and South Carolina, found that budget and career constraints lead many parents to prioritize accessibility and affordability over quality. In other cases, they may decide to drop out of the labor force to avoid the expense of child care altogether. Due in part to the cost of child care relative to earnings, mothers of preschool-aged children in rural parts of the Fifth District are more likely to be out of the workforce than urban mothers of preschool-aged children; according to Richmond Fed analysis, 65 percent of rural mothers with preschool-aged children participate in the labor force, compared to 70 percent of urban mothers of preschool-aged children.

At the same time, rural communities throughout the Fifth District have developed strategies for addressing these challenges using public resources, community-driven interventions, and public-private partnerships. For example, the Town of Kershaw in Lancaster County, S.C., coordinated public, nonprofit, and private funding to convert an unused former bank building into a child care and early education center, reducing the upfront fixed costs associated with opening a new child care business. Hardy County, W.Va., took another approach, establishing and maintaining a coalition of partners in the public and private sector, which reduce the overhead cost to local child care businesses by providing free technical assistance and in-kind support.

Health and Health Care

Poor health may also be keeping some rural workers out of the labor market. The evidence of poor health in rural areas takes many forms. In a 2018 paper, John Coglianese of the Fed Board of Governors found that about 75 percent of male prime-age dropouts reported disability as the reason they are not in the labor force. This research suggests that disability is a major factor in the increasing trend of prime-age White males exiting the labor force. And self-reported rates of disability skew higher in rural areas relative to urban areas, even after controlling for demographics and socioeconomic status.

The opioid epidemic also hit rural areas particularly hard, including in the Fifth District, and has been highly disruptive to employment. (See "The Opioid Epidemic, the Fifth District, and the Labor Force," Econ Focus, Second Quarter 2018.) David Peters of Iowa State University and co-authors found in a 2020 article that most U.S. counties facing a prescription opioid epidemic were in rural or nonmetropolitan counties. In a 2017 article, the late Alan Krueger of Princeton University found that prime-age males not in the labor force were more likely to reside in counties with high rates of opioid prescriptions.

Numerous other health outcomes tend to be worse in rural areas: Hypertension, smoking, and obesity rates are all higher in rural areas. Infant and maternal mortality increases with rurality, and there are more hospitalizations for dental-related emergencies. Rural communities also have higher prevalence rates for doctor-diagnosed arthritis for nearly all populations. Accidental deaths from injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and drug overdoses tend to be higher in rural areas as well. What is more, rural counties have lower rates of college graduates, higher poverty rates, and lower rates of health insurance than urban counties — all of which are important factors in health.

The correlation between health and employment is evident in the Fifth District. In the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute's County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, which ranks counties within each state on a range of health outcomes and health-related factors, Fifth District urban counties tend to rank higher (healthier) than rural counties. In Virginia, for example, the 15 counties with the highest health-related quality-of-life outcomes have a combined employment-to-population ratio of 81 percent. All but one of these counties are urban. Conversely, the 15 counties with the lowest rankings for quality of life, 12 of which are rural, have a combined EPOP of just 58 percent.

Rural communities often face challenges to developing a local health care workforce as well as recruiting providers to locate in smaller towns. Roughly two-thirds of the Fifth District's health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) as defined by the Health Resources and Services Administration are in rural or partially rural areas. These designations are based on criteria such as their population-to-provider ratio and the average travel time to the nearest site for care, and reflect the unmet need for dentists, mental health professionals, and primary care providers. In the Fifth District, nearly all nonmetro (rural) counties are either partial or full HPSAs for primary care. And the nationwide nursing shortage is especially acute in rural areas; many rural hospitals have reported turning away patients due to a lack of nurses. (See "The Rural Nursing Shortage," Econ Focus, First Quarter 2022.)

Programs aimed at supporting health care careers for local residents, like the Goodwill Industries of the Valleys GoodCare Program, can build up a community's health care workforce and improve access to care. Improving recruitment and retention of health care workers through incentive programs, like student loan repayment programs in return for serving in high-need areas, can incentivize physicians and other health practitioners to serve rural populations. Policies and funding that supports broadband deployment can connect rural residents to health resources and access to health providers via telemedicine that are inaccessible in remote areas.

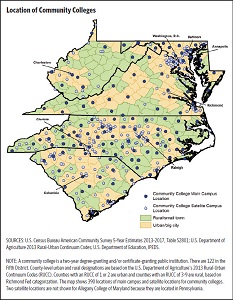

The Digital Divide

Health care is just one of the many critical needs filled by broadband. As discussed in the Richmond Fed's Community Scope article "Bringing Broadband to Rural America," high-speed internet service has transitioned from a luxury good to an increasingly necessary utility. Studies have shown the positive effects of broadband access and adoption on business location decisions and employment growth in rural areas. Moreover, some proposals for expanding access to community colleges in rural areas rely on broadband. But broadband service continues to lag in rural areas. (See "Closing the Digital Divide," Econ Focus, Second/Third Quarter 2020.)

There are a number of approaches to expanding broadband infrastructure. For example, the Choptank Electric Cooperative on Maryland's Eastern Shore is an example of how many electric cooperatives are providing broadband service in rural communities. The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) includes significant funding for broadband infrastructure and deployment. According to an analysis by the Biden administration, a minimum of one-third to one-half of unserved Fifth District residents will receive access to broadband services from the IIJA deployment funding. And around 30 percent of West Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina residents will be eligible for the IIJA's broadband affordability subsidies, along with 23 percent of Virginia and District of Columbia residents, and 17 percent of Maryland residents.

Building on Assets to Address the Challenges

Although the barriers that rural residents face in education, training, health care, housing, transportation, child care, and broadband access are not unique to rural areas, understanding how those challenges manifest themselves in rural areas in a different way than in urban areas is critical to identifying solutions. For example, in transportation, a better public transportation system of buses and trains might be the most cost-effective solution in an urban area; in a rural area, we might need to think creatively about novel ways to physically connect residents to employment.

There are many examples across the District that highlight the ingenuity and creativity of local policymakers to address the challenges. (For more information, view our Rural Spotlights series.) Identifying and taking advantage of the unique assets that rural communities have will continue to be a critical piece of the puzzle.